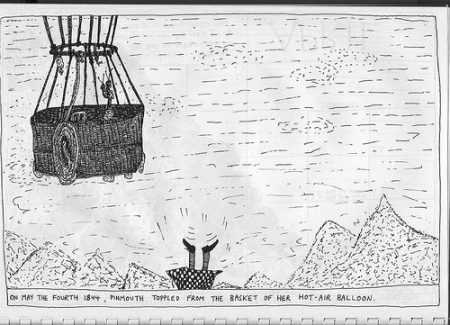

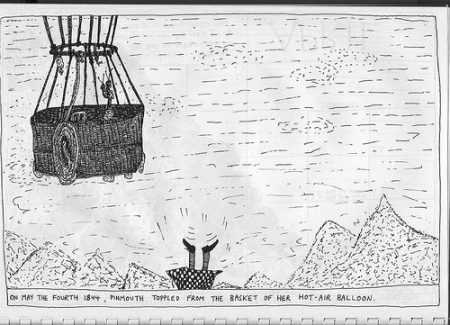

Here is another picture from the Hooting Yard Calendar 1992. This one shows Pinmouth toppling from the basket of her hot air balloon on May the fourth 1894.

Here is another picture from the Hooting Yard Calendar 1992. This one shows Pinmouth toppling from the basket of her hot air balloon on May the fourth 1894.

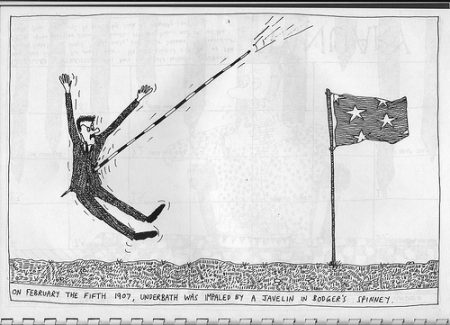

Can it be that a quarter of a century has passed since the publication of the Hooting Yard Calendar 1992? Tempus bloody well fugit, and no mistake. The calendar that year was entitled “Accidental Deaths Of Twelve Cartographers”, and here is one such accidental death, that of Underbath, who, we are told, was impaled by a javelin in Bodger’s Spinney on February the fifth 1907.

I am old enough to remember – albeit dimly – the Latin Mass. For younger readers, and non-Catholics, I should explain that until the mid-1960s, throughout the Catholic church, Mass was conducted exclusively in Latin. The priest would deliver the liturgy in Latin, and the congregation, when required to voice responses, would do likewise. The change to the use of the vernacular came about when Pope John XXIII instituted various liberalising reforms. There remain a few recalcitrant diehards – notable among them being the father of Mad Max star Melvin Gibson – who cling to the Latin Mass, although I understand this is much disapproved of by the Vatican, and may even be illegal.

On the council estate where I grew up, there were many Catholics but no Catholic church. To save us from having to trudge a fair distance to St Bede’s, the parish church, an arrangement had been made that a pub on the estate would host our Sunday Mass. Thus every week we would troop into the Moby Dick on Whalebone Lane. We used the main bar area of the pub, with chairs temporarily aligned in rows, though I cannot recall what served as an altar. I do remember that towels were draped over all the beer pumps at the bar. After Mass, a goodly proportion of the congregation, and probably the priest too, would remain in the pub waiting for opening time. My parents were not drinkers, though, so we were herded home.

Around the same time as the introduction of the Mass in English, the service itself was moved to a new community centre on the estate. Thus passed a particular, and in retrospect profound, part of my childhood.

I stopped attending Mass when, as a nincompoop teenager, I turned my back on the faith. Then, and for many years afterwards, if I thought about the Latin Mass at all, it was as a prime example of the stupidity of religion. How preposterous, for people to gather together to listen and respond to what for most of them (and certainly for the infant me) was a babble of incomprehensible gibberish!

It is only recently that I have realised the significance of this early experience. One must bear in mind that for the vast majority of people, there was nothing remotely swinging about the 1960s. Particularly on my council estate, it was a dull, pinched, grey (or beige) time yet to emerge from the austerity of the immediate post-war years. We had no television, telephone, refrigerator, central heating, or other home comforts. Life was uneventful and devoid of any but the most paltry excitements. (I now look back with nostalgia for the peace and tranquility.)

There was thus something quite magical and passing strange about those Sunday mornings. We gathered in the gloom of the pub, while a man dressed – improbably – in often colourfully embroidered raiment stood, with his back to us (as the priests did in those days), intoning a litany of words, and always exactly the same words, which we did not understand, and bore no relation to anything we heard elsewhere, in any circumstances. Indeed there was nothing about it that had anything whatsoever to do with the world we inhabited the rest of the time. It was baffling and bizarre, but, by dint of weekly repetition, comfortingly familiar. And it was deeply, deeply serious.

It has now dawned on me, at long last, that, in my own faltering yet determined way, I have been trying to recreate this numinous childhood experience by babbling, once a week, in Hooting Yard On The Air on ResonanceFM.

From his banishment in a pompous land, Mike Jennings writes to suggest that I exhume the piece Dim Tyrant, posted here in 2010. “The dim tyrant, Crepuscus VIII, would seem very relevant all of a sudden,” says Mr Jennings, “Given his, quote, fateful combination of childish whimsy and an inability to string together a coherent sentence, unquote.” What POTUS could he possibly be thinking of? Anyway, here is the piece, which does seem, at least in its earlier passages, spookily prophetic.

Assessing the career of the tyrant king Crepuscus VIII, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that he was excessively dull-witted and dim. There is a plethora of anecdotage, from courtiers and palace leeches, revealing that the king was rarely able to answer simple questions such as “What part of the body sits atop the neck?”, “How many angels can dance upon the head of a pin?” or “Who won the 1953 FA Cup Final?”

And yet this atrociously stupid man ruled over a mighty kingdom for many years, his hands steady at the helm though his mind was doolally. So, dim as he was, he has much to teach us about the craft of kingship, and indeed of tyranny, if we consider tyranny a craft. For let there be no doubt that his reign was tyrannical.

“In the case of Crepuscus VIII,” wrote the historian Sagely, sagely, “we find a fateful combination of childish whimsy and an inability to string together a coherent sentence. Thus it was that his henchpersons invariably misunderstood his ukases, but hurried to fulfil them come what may.” Sagely gives as an example the occasion when the tyrant king’s whim was to burn down every barn in the land. But so muddled and mangled was the manner in which he gave the command that his Royal Barn Burner mistakenly put a pot-belled pig in charge of the palace treasury instead. As might have been expected, the pig spent every last golden coin on swill, and not a barn was burned to the ground. Fortunately, Crepuscus VIII was so dim that he did not realise what had happened, nor why, and he retired to his boudoir to gaze at the ceiling, thinking it was the vault of heaven.

One could multiply such flimflam until the cows come home, and indeed there are many amusing – and sometimes alarming – books which cobble together hundreds of instances of Crepuscus VIII’s imbecility. I want to take a slightly different tack, however. The thing that has always fascinated me about the tyrant king is not his breathtaking dimness but his dinner jackets.

Dinner was of supreme importance at the court of Crepuscus VIII. Whatever else was going on, at four o’ clock sharp every day, the king would sweep into his banqueting hall and sit down at his banqueting table, at which would be gathered all sorts of banqueting companions. In spite of his dimness, the king liked to be entertained during dinner by philosophers, scientists, novelists, artists, actors, clowns, jugglers, pamphleteers, scruffily-bearded film directors, engineers, podcast maestros, deep sea divers, chefs, snipers, ornithologists, sundry persons with metal plates in their skulls, magicians, mountaineers, ex-Beatles, priests, anthropologists, cartographers, architects, mesmerists, and, if he was available, Rolf Harris. It is doubtful if any of the high-flown table talk penetrated the king’s dull-witted brain, but he sat there, a fork in each hand (he never used a knife), beaming, and resplendent in his dinner jacket of the day.

There were seven of these jackets, one for each day of the week, and the king cut quite a dash in all of them. Monday’s was made of crimplene and cardboard, with golden stars and ribbons and a coathanger embedded in it. Tuesday’s was of plain burlap sacking, adorned with coal dust and grease. Wednesday’s was a gorgeous embroidered flapping wonder. Thursday’s was satin, boxy and black. Friday’s was knit from strands of a rare and stinking wool, shorn from rabid sheep, tie-dyed like some hippy shawl, surrounded by an aura invisible. Saturday’s was of classic cut but frayed at the cuffs, with dangling bells. Sunday’s was somehow a blur, as if the king was vibrating, or on another plane just beyond human apprehension. Whatever day of the week it was, whichever dinner jacket he was wearing, the tyrant king ate sparingly, birdseed and millet mostly, accompanied by sips of lukewarm water from the palace spigot.

Today the dinner jackets can be found hanging in display cases in a jolly little museum hidden away in one of the less salubrious faubourgs of Pointy Town. I exhort you to pay a visit, nay, repeated visits. Study the jackets, now caked with dust, hear the echoes of all that banqueting table babbling, take away with you a souvenir packet of Tyrant King’s Birdseed®, relive the days when Crepuscus VIII reigned over us, dim and tyrannical and cutting quite a dash.

The part of the body atop the king’s neck, by the way, was his head.

The other day I mentioned Biff Chomsky’s chart-topping album of sentimental ballads entitled Songs For Drowned Kittens.

By curious coincidence, yesterday I listened, for the first time in God knows how many years, to One Lonely Night. This is a “Cold War operetta” by The Massed Ranks Of The Proletariat, adapted from the novel by Mickey Spillane. The lyrics are by Ed Baxter. It was released as a severely-limited edition cassette tape in (I think) 1990.

Anyway, have a listen to Mike’s death-wish song and you will understand why I was struck by a spooky sense of connection to the past.

By popular demand, here is another verse by a sulky Bulgarian poet, written circa 1982. This one is entitled O, Little Radish and purports to be by Fratsin K Yecebit. (My poets’ names sound Turkish rather than Bulgarian, but I was young, so young …)

Tomorrow morning we will

Drink vinegar

Here in this trench.

I haven’t paid

Any of my debts

And I don’t intend to.

They can brandish guns at me

Or twigs.

I’ll make my peace

And whip it up with a whisk.

Send me your cash now.

Send me the lot.

I’m the man you ought to

Shove in the vat.

Along with the Undimmed by Death postcard, I unearthed another set of six cards from the same era. These are hand-drawn and hand-written, and collectively titled Sulky Bulgarian Poets. Unfortunately, the drawings are cack-handed and the “poems” are atrocious – with one exception. Number 5, “In Fish And Shipping”, is attributed to sulky Bulgarian poet Elvis Targnegescubit, and, though it pre-dates Hooting Yard, I think it is a worthy addition to the canon.

In despicable visions of

An unholy refrigerator,

Another refrigerator,

In implacable discussions of

A swordfish,

A carp,

An enormous schooner,

A small schooner,

A tiny ship, ship-ette,

In all these I have said,

Irrefutably, not once,

But with venom,

I am a very fat man.

In 1982 I spent much of my time making postcards, which I sold for a pittance to eager punters from what would now be called a pop-up stall in Norwich. Below is an example of the sort of thing I was doing.

The source material for both words and images was a huge pile of National Geographic magazines from the 1950s and 1960s acquired from various second-hand bookshops. To create the captions I employed a cut-up technique akin to that used by William S Burroughs and David Bowie, but far more amusingly than either of them ever did, particularly the former, a tedious gun-toting drug-addled uxoricide.

Younger readers may find it difficult to fathom, but in Norwich in 1982 it was well nigh impossible to find an affordable colour photocopying facility. I thus sent my originals to my friend Peter Ross in London, and Peter organised the copying and sent me the results by post. I then employed scissors and glue to mount the hysterically funny images on to card, ready for sale to East Anglians.

I think Peter is still in possession of most of the original artwork, but this one came to light the other day. The captions read as follows:

Undimmed by Death

Who were they?

In this convivial land, trendy youngsters like Walter And Jorg searched the ground for clues.

Walter and Jorg are each identified by separate name captions.

In a review of a new biography of Thomas De Quincey, Hermione Eyre brilliantly describes him as “broke, pompous, and high as a kite”. Could the same, I wondered, be said of Mr Key? Let us take them in turn.

Broke. Definitely. I have a very limited income, and I lead a very frugal life. I am deeply grateful to my subscribers and those who make one-off donations (you know who you are) who help to alleviate my penury. I did entertain the fantasy, last year, that Mr Key’s Shorter Potted Brief, Brief Lives might become a huge international bestseller and thereby bring the wealth of Croesus showering upon me, but of course this failed to happen. Writing is not a sensible pursuit if one wants to become rich.

Pompous. I try my best to burnish my pomposity. Declaiming and pontificating, particularly upon subjects I know little or nothing about, is a helpful approach in this regard. It is also important not to behave, or even think, as if one is broke (see above). In fact, reduced circumstances can make pomposity easier to achieve. Having little justification to assume an air of grandeur, my attitude of rising high above the riffraff is most surely pompous, and I would have it no other way.

High as a kite. This is where I am unable to compare myself to De Quincey. In the last century, I could have done. An American editor, considering my early work, wondered if I wrote under the influence of hallucinogenic drugs. (This is referred to in David Langford’s 1993 article, here.) While I eschewed illegal drugs, I was pretty much perpetually drunk for the last twenty years of the twentieth century, so I suppose it is true that all my early writing was done when I was high as a kite, or pissed as a newt. Eventually, of course, my debauches left me unable to string a coherent sentence together, and I was reduced to bestial grunting on the way to and from the off licence.

I swore off booze in 2001 and haven’t touched a drop since then. At first I did worry that perhaps clear-headed sobriety would scupper my prose, but of course it didn’t. Every so often I toy with the idea of writing one of those booze-memoirs, but the thing about drunks and druggies is that we are very, very boring. Unless, like Thomas De Quincey, we are touched by genius.

One of my favourite Hooting Yard characters is Detective Captain Unstrebnodtalb. He made his first appearance long ago in the last century, in The Immense Duckpond Pamphlet:

The next day all hell broke loose. Early in the morning, as Blodgett polished the outside spigots, an ogre or wild man hove into view atop the southern hills. Its progress towards the House was implacable. It stamped through the bracken, vaulted the ha-ha with a single bound, negotiated the massive basalt wall with surprising elegance, and sprang towards the terrified Blodgett, whirling its hirsute arms alarmingly and making disgusting guttural noises. It was matted with filth. Flies, gnats, and tiny things emitting poisonous goo crawled all over its flesh. It seemed to be decomposing. It drooled. It picked up Blodgett, sank its fangs into his skull, and hurled him aside. Pausing momentarily to spit out particles of Blodgett’s head, it smashed its way through the wall of the House, oblivious to the fact that there was an ajar door three feet to its right. Once inside the House, its rage seemed to increase. It rushed wildly from room to room, obliterating the furniture, tearing up floorboards, destroying chandeliers, bashing holes into walls and ceilings, sucking the wallpaper off the walls. It chewed up banister rails and regurgitated them, disgorging them with such force that each rail acted as a lethal projectile. At least one of the urchins was impaled as a result. Five minutes after the ogre’s arrival much of the lower part of the House lay in ruins. Small fires were starting, but they were doused by water spurting from uprooted taps. Euwige and Jubble were still sprawled in the Bittern Room when the ogre eventually came upon them. It let out an inhuman cry. It picked at its sores. It became becalmed. Fixing it with a bemused stare, Jubble rose to his feet. “You know, there might still be some grog left,” he said, “Would you care for a drop?” The ogre pounded its fists against its own head. Then it blinked, shuddered, twitched. Jubble pushed a tin mug of grog into its paw. It gulped the sweet muck down greedily, then threw the mug back at Jubble, missing his ear by a whisker, as they say. Something in its manner seemed to change. By now, blind Euwige too was on her feet. She sniffed at the violent pongs emanating from the ogre, then stepped towards it. “Thank heaven! You have come!” she said, “Jubble, meet my dear friend Detective Captain Unstrebnodtalb! He comes from a far country, and his brain is hot.”

The usual pronunciation of vase, in this country, is as a rhyme with mars. In the United States, it is more common for vase to rhyme with lace. Growing up on an Essex council estate with a Belgian mother whose native tongue was Flemish, however, I learned to rhyme vase with jaws.

This was but one example of my mother’s idiosyncratic English. She spoke of the old films we loved to watch as being “in white and black”, and regularly deployed a sort of guttural expostulation my sister still refers to as “the Flemish sound”. This was used to express a vast swathe of emotions, from surprise to incredulity to contempt to disgust to … well, pretty much any response.

The word chasm is one that we probably encounter more in written than spoken English. My mother pronounced it with a soft ch, as in chase or chicken. So I did too, on the rare occasions I said it aloud. I only learned the correct, hard c pronunciation in my late teens, when I was reading a passage aloud in an English class at school and my teacher raised an amused eyebrow. He gently corrected me when I finished reading.

Many years have passed, but I still find myself drawn inexorably to the pronunciations I learned at my mother’s knee. And, intriguingly, my sister finds herself increasingly using “the Flemish sound” as she grows older.

Following the mothballing of The Dabbler, my sister Rita has launched a new home for her Dispatches From The Former New World. Make sure you keep a close eye on it. Bear in mind that Mr Key would not be the scribbler you know and adore were it not for the influence, from a very early age, of this woman – last spotted here wearing a mortar board outside Brighton Pavilion.

Today is the feast day of the Jesuit martyr St Edmund Campion. In the long ago, I attended a grammar school which bore his name. Each year, on the first of December, the school celebrated its patron saint by making all the pupils between the ages of 11 and 16 engage in a cross-country run. On a bitterly cold December morning, then, instead of sitting in a classroom poring over a Latin textbook, we would stand assembled in a field, shivering in skimpy running kit, awaiting the barked order from a teacher which would send us scurrying and squelching through mud and puddles for a seemingly interminable race.

I was not an athletic child, and the prospect of these runs filled me with something close to despair and rage at an unfair universe. In the first year, I avoided it by remaining at home in bed, moaning weedily and convincing my parents I was suffering from a terrible malady. In the second year, I contrived to be knocked down by a car on the way to school and spent the morning in a hospital bed from which I was ejected, being unharmed, by midday. In the following three years, however, I took part in the annual cross-country run.

We are not talking about the real countryside here. The school was located in suburban Essex, so the “country” across which we were forced to scamper was a few fields and patches of scrubland in the vicinity. It was a bleak and awful landscape of mud and brambles and nettles and muck. pitted with puddles, often beset by driving rain and howling winds. Much as I loathed every second of this annual horror, I realise now that it had a powerful effect on my imagination, for if that is not a Hooting Yard landscape, what is?, what is?