I was not surprised, when I set out to reacquaint myself with Robert Wyatt’s complete back catalogue, that memories came flooding back. The earlier part of his career coincided with my adolescence, that time when some of our enduring enthusiasms lodge themselves in our souls. Wyatt was my great musical hero when I was fourteen, and he remains an abiding figure, even if I no longer worship him, as I did then, as a god. But listening to the very first records, with Soft Machine, prompted memories of another of my teenage talismans, and more particularly of something irrevocably lost, and lost not just to me but to everyone.

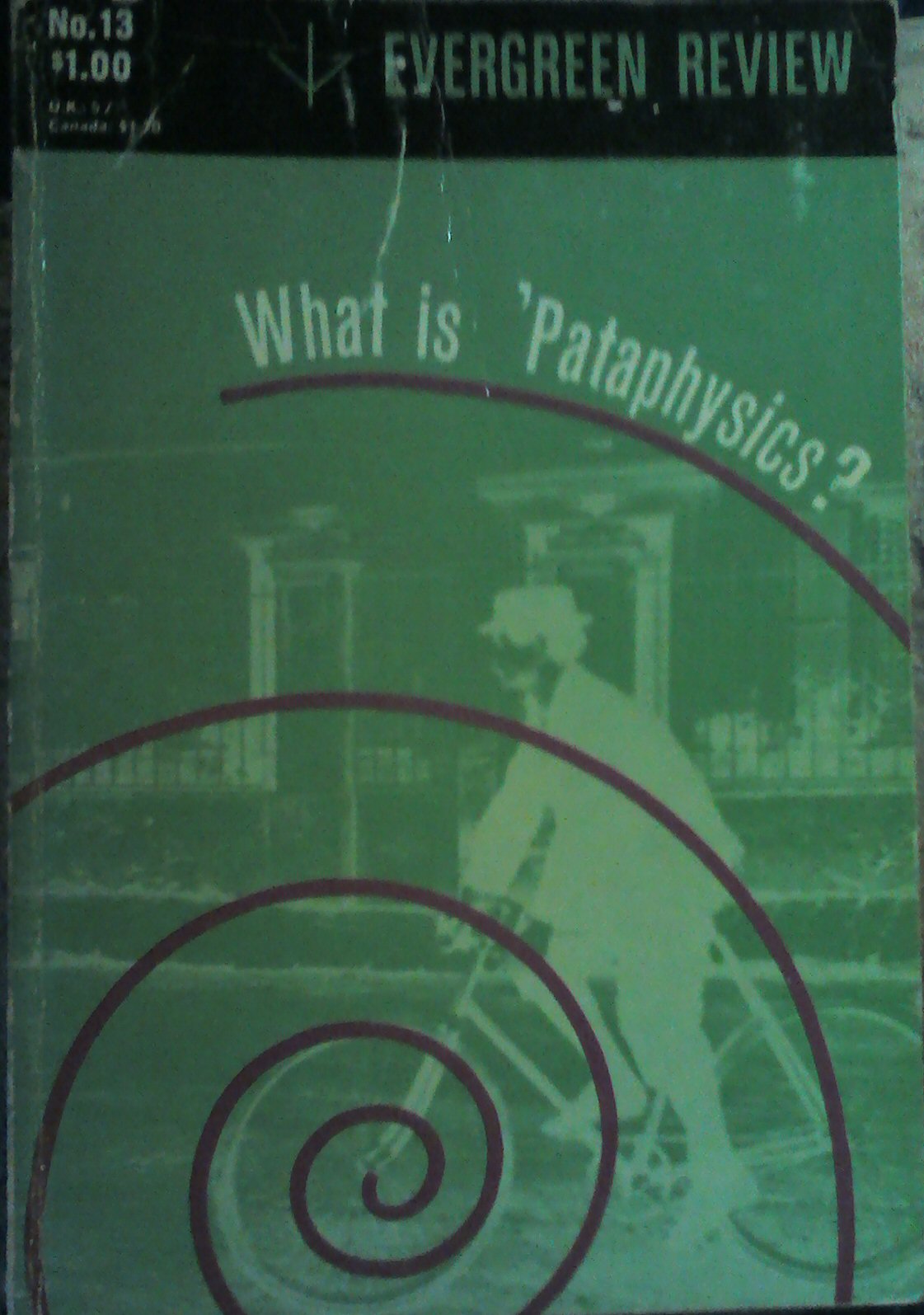

At the beginning of Soft Machine Volume Two, Wyatt announces that what we are about to hear is “a choice selection of rivmic melodies from the official orchestra of the College of ‘Pataphysics”. Like many another spotty youth with intellectual yearnings, I pored over the lyrics of my favourite albums, and in this case I wondered: was there really such a college?, were Soft Machine really its official orchestra?, and, er, what the hell was ‘pataphysics anyway? That word rang a faint bell, and it was not long before I recalled where I had heard it before. “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” from Abbey Road – arguably the most irritating song in the Beatles’ canon – opens with Joan studying “’pataphysical science in the home”.

Because it was Wyatt, because it was intriguing, because it was obscure, I wanted to find out more about this ‘pataphysics business. But where to start? And that, precisely, is what we have lost, that question of where to start. If I were a teenager today, the question would not even occur to me. I would head straight for the wikipedia. From the comfort of my smelly sock-strewn bedroom, and pausing only for the occasional pot noodle, within a few hours I could find out all I wished to know about ‘pataphysics, familiarise myself with the life of Alfred Jarry, download the texts of his plays and prose, and veer off in other promising directions, towards Dada and surrealism. By the time I tumbled into bed my head would be crammed with the knowledge that, four decades ago, took me years to acquire.

And this, I think, is a great loss. Complete access to everything all the time seems – and sometimes is – wondrous, even miraculous. But what is lost is the pleasure of pursuit, following a trail, serendipitous discoveries, unexpected byways, and – most importantly – the time taken. The instant availability of all that information to me, aged fourteen, could never be as valuable as the process of its gradual acquisition over months and years.

Where I did begin was with my parents’ bookshelves. I have written before about the experience of growing up on a bleak council estate, but of course I was never culturally impoverished. Quite apart from the teeming bookshelves, I was a bus- and Tube-ride away from London. Also, back then, my local library was still a building filled with books, and not the “chat-‘n’-snack zone” (in the approving words of Labour’s last “culture” secretary) it, and so many others, have become.

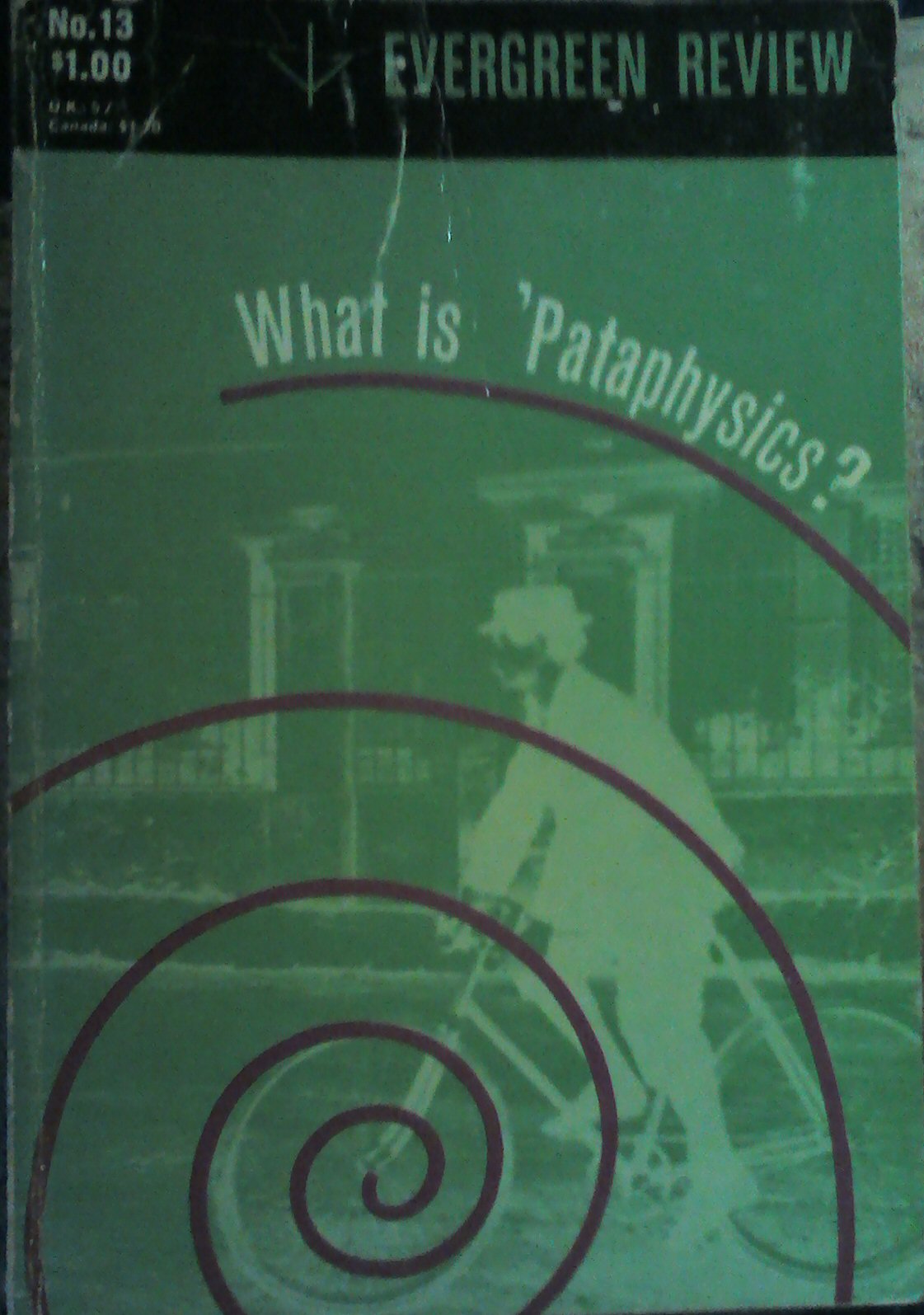

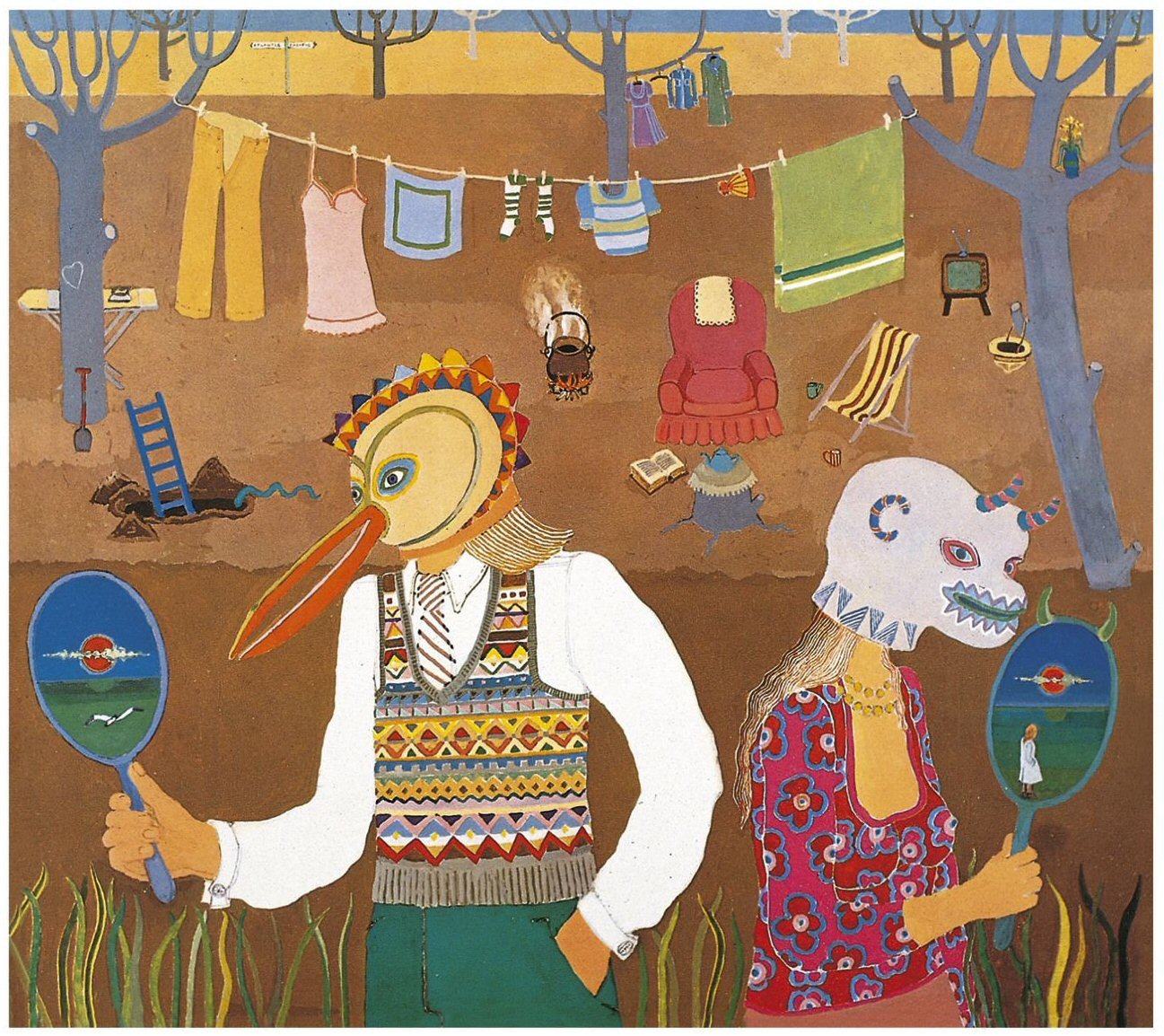

Unfortunately, eclectic though my parents’ tastes were, they did not run to a love of screechy-voiced madcap alcoholic visionary French writers of the fin de siècle. I was able to dig out stray references in some of their many art books. Further mentions popped up from time to time in the pages of the dear old NME in its halcyon days, usually in interviews with some of my other favourites like Slapp Happy or Henry Cow. In the library I found a copy of Ubu Roi. I somehow discovered the existence of a book called The Banquet Years by Roger Shattuck, a quarter of which was devoted to a biography of and critical essay on Jarry. I remember asking my father to buy it for me the next time he popped into Foyle’s (which was pretty much every week.) On one of my own forays into town, at a time when Charing Cross Road was packed with bookshops, I found a Jonathan Cape anthology of Jarry’s Selected Writings. And one day I was unreasonably overexcited to receive in the post, as a gift from my sister in America, a copy of the Evergreen Review (Volume 4, Number 13, May-June 1960), a 190-page paperback special issue entitled What Is ‘Pataphysics? It remains one of my most treasured possessions.

The point is that this was all very piecemeal and gradual, and therein lay the pleasure – of pursuit and discovery, stretching over time. It is a pleasure to a large extent lost. Had I not sworn off the booze, I would celebrate it, mournfully, in the spirit of Alfred Jarry, with a couple of bottles of wine and a pint of absinthe before breakfast. No wonder he was dead at thirty-four.