Before plunging into the ocean, snorkelled and flippered or, as it may be, encased in full body diving gear, it is critically important that you are aware of the actual size of the innumerable life forms that teem within the vasty deep. If you have read Pebblehead’s bestselling paperback The Neurasthenic Aquaperson, you will appreciate the force of my argument. In this book, the author ploughs through a relentless litany of aquatic diving enthusiasts of a nervous disposition who came a-cropper in the water because they feared an encounter with some monstrous sea-being whose picture they had pored over in an album of marine life, without having taken care to read a parenthetical addendum to the caption saying (actual size) or (not to scale).

For the hearty and the reckless, of course, there is no problem. They will topple off the side of their boat and go happily splashing about in the depths with the same gusto they would take to striding across a wild and desolate moor, or tucking into breakfast in a magnificent hotel dining room. But woe betide the mentally fragile diving person, one who suffers from attacks of the vapours, should they jump into the broiling ocean unprepared!

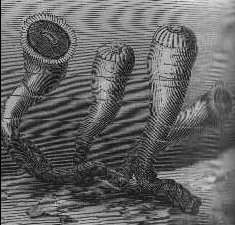

Let us consider an example. Here is a picture of Zoanthus socialis:

Pebblehead acknowledges that many nerve-wracked oceanic explorers will prepare themselves by swallowing a draught of some brain tonic or emboldening potion before clambering into their wetsuit. He condemns this practice, rightly in my view, in prose of towering vigour. “There can be no substitute,†he writes, “for preceding each dive into the squalid black depths of the oceans with untold hours of study of the actual size of thousands, nay, millions of grotesque life forms that populate those very same squalid black depths into which the neurasthenic aquaperson is due to plunge!â€

Some cynics have pointed out that Pebblehead has a vested interest. He owns the rights to a patented mechanism by which the prospective diving person is able to stand before a full-length mirror and watch as, one after another, actual size images of numberless sea-beings are superimposed upon his or her body. An accompanying set of tomes contains colour plates of each creature, fully captioned in English and Latin, which can be consulted during the slide show, or separately. This seems to me to be a wholly admirable enterprise, and it is no skin off my nose if it earns Pebblehead a fortune. Indeed, one might ask what comparable service to humanity, neurasthenic or otherwise, is being provided by other bestselling paperback authors. Perhaps I am being unfair to the likes of Andy McNab, Barbara Taylor Bradford, and Martin Amis, but where oh where are their initiatives to give succour and hope to jangle-brained aquapersons, pig farmers, posties, stamp collectors, bellringers, detectives, pie shop proprietors, and conquistadors? Pebblehead deserves a medal, or at least a tin cup, and I for one will happily campaign on his behalf. I shall be outside the town hall with a placard and a flask of tea at six o clock tomorrow morning, and every morning. Join me.