Forgive me if I lapse into a wee splurge of self-referential twaddle, but I thought I would mark the end of the first quarter of the year with a review of my daily essays project. Back on the first of January, in On Perpilocution, I set myself what I described as a “foolhardy” task, to write roughly a thousand words a day on whatever topics arrived in my head. I was pretty well convinced that this plan would fail, probably about halfway through January. (A few years ago, I had the less rigorous ambition of updating Hooting Yard with a daily postage, of indeterminate length, and this collapsed early on when I missed a day.) So I am mightily surprised to have got through three entire months without a hitch.

On three occasions, I cheated, in that I reposted older pieces from the archive, though in each case they were sufficiently elderly that they may well have been new to the less than indefatigable devotee. And one day in February I was pleased to offer Hooting Yard space for a guest postage by the blogger BlackberryJuniper And Sherbet for her expert analysis of the magnificence of Peter Wyngarde, a topic she is far better qualified to address than I am. Other than on those four days, I have managed to bash out around a thousand words.

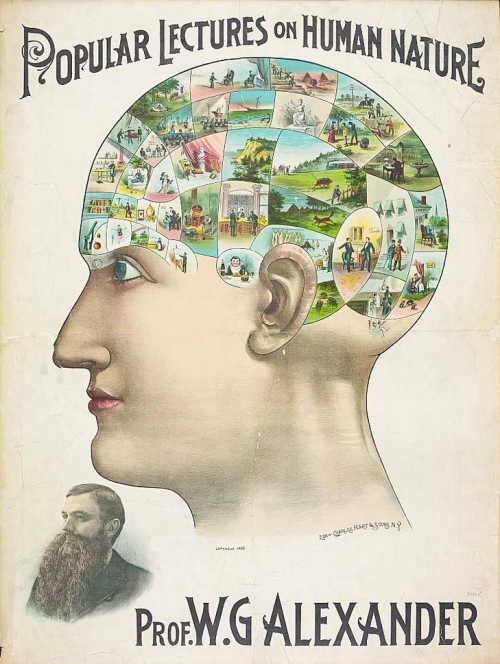

Including those mentioned above, the essays covered perpilocution, the moustache of Archduke Stephen, Palatine of Hungary, east and west and left and right, potatoes, fogous, naming your child after your favourite reservoir, the falsely negative portrayal of U-boat sailors, voodoo athletics, my father, gulls’ eggs, clunks, Skippy the bush kangaroo, feral goblins, first encounters, tin foil, apps, control of the fiscal levers, Babinsky’s idiot half-brother, the Goliath bird-eating spider, Dickensian characters, true grit, barking up the wrong tree, government-controlled origami, Porridge Island, the devil in the detail, Speed, the Latin Mass and Moby-Dick, quadruple points, truculent peasantry, The Love Song Of Ah-Fang Van Der Houygendorp, scree, blessing cotton socks, the collapse of civilisations, the administration of lighthouses, groovy bongos, Balaam and his ass, replacement bus services, “the Scottish play”, groaning minions, having the prize within one’s grasp, nitwits, gods, the lambing-hall boogie, Pontiuses, the one-eyed crossing-sweeper of Sawdust Bridge, certain books I have read, the magnificence of Peter Wyngarde, sand robots, birds, my own Zona, The Wellspring Of Debauchery, a yapping dog and a bramble patch and a bog, the dubbin club, jelly, Belgian archery, marshy punting, a darkling plain, silent monkey, counting corks, the screaming abdabs, the air, a spook’s briefcase, etiquette, “on and on and on,” dreams of Pointy Town, chairlift dingbats, mods and rockers and widows and orphans, the plains of Gath, curlews, the thing that smelled of birds, pickles and pluck and gumption, fate, reggae for swans, the newty field, a couple of art exhibitions, Soviet hen coops, certain ants, bravura bunkum, Captain Nitty, the bad vicarage, sudden darting movements in the insect world, the pecking order, my transformation, bringing the good news from Ghent to Aix, the naming of nuts, razzle dazzle and its avoidance, the balletomane Nan Kew, King Jasper’s Castle, Its Electrical Wiring System, Its Janitor, And Its Chatelaine, King Jasper’s bones, and eggheads. I think there is a pleasing variety of subject matter, and I have done my best not to bang on and on about the same old guff day in day out.

I do wonder how many people actually bother to read all of these outpourings, and have had a few crises of confidence, when siren voices called to me to chuck the whole thing in, and put my feet up, and return to conventional itsy bitsy blogging. But, as Outa_Spaceman discovered with his cardboard signage project in 2011 – which inspired the idea of the daily essays – a plan such as this has its own momentum. I reached the point a fair few weeks ago where I could not imagine allowing the day to pass without its allotted screed.

Two things occur to me on looking at that list above. One is that I have made use of almost none of the suggestions made by helpful readers in response to my plea, in On Perpilocution, to nominate topics I might profitably address. This may make me seem dismissive and ungrateful. I am anything but. I am consciously keeping many of those suggested titles in reserve. Bear in mind we have three-quarters of the year yet to come, and who knows when I might be struck by a more severe case of vacancy-between-the-ears than has yet afflicted me? The sense of security in having a batch of possible essay titles available to me in times of mental befuddlement is most welcome. So thank you – and keep ’em coming!

The second thing that occurs to me is that it might be interesting to rearrange the essays into something approaching alphabetical order, for the forthcoming paperback edition. This should be available very shortly, I hope, entitled Hooting Yard Quarterly, Volume I Number I, Spring 2012. Alphabetical order would grant the collection an encyclopaedic air, and it has long been my ambition to present the world with an encyclopaedic body of knowledge wrung from my cranium. This might also help me to identify gaps. Well, we shall see what the next quarter of the year brings. By the end of June, if all goes according to plan, there should be another ninety-one essays, on divers topics, posted here daily.

Do bear in mind this is serious work undertaken in a serious frame of mind, with not a jot of levity.