There are, apparently, half a million ponds in Britain. This is not nearly enough for the charity organisation Pond Conservation, which has plans afoot to double the number, presumably to the point where the country is more pond than land. I turn my attention to the Million Ponds Project over at The Dabbler this week. Warning : contains bloodsucking leeches and bloodcurdling screams.

Monthly Archives: September 2012

On SPEC. NO. 40642

Before reading the following, gaze at the picture above for a goodly amount of time. You may wish to enlarge it to poster size, print it out, and pin it to your noticeboard or wall.

The photograph shows a boffin and a mouse. Also shown is certain arcane laboratory equipment, and a stencilled panel marked SPEC. NO. 40642. It is not clear whether this designation refers to the equipment, the mouse, or the boffin. Let us not bother our little heads about it.

At first glance, it appears that the boffin is studying the mouse, and making notes in a ringbound notepad, presumably appertaining to the mouse. The mouse is encased within some kind of lidded laboratory bowl, for which I do not doubt there is a specific proprietary name, of which I am tragically ignorant. The bowl is attached by a tube to the arcane laboratory equipment and also, by wire, to something else, unseen, out of camera shot. We might spend all day lost in conjecture about precisely what that might be.

We might, but we won’t, because we have other matters to attend to. Though it is a racing certainty that the above summary is correct, and that the boffin is indeed studying the mouse, there is an alternative possibility, albeit an unlikely one. Consider again that the boffin is quite clearly making notes. It could be that she is not a boffin but an amanuensis, and is actually taking dictation from the mouse. Though the general run of mice are not gifted with human speech, this mouse might be an exception. Or it may be that the boffin-amanuensis is gifted with an understanding of mouse squeaks, and is able to transcribe them for the benefit of other humans not so gifted. As I say, this is unlikely, even outlandish, but it is not beyond the bounds of possibility.

I would dearly love to see what is written in that notebook.

On purely pictorial evidence, we would have to swat aside my foolish mouse-dictating-to-amanuensis scenario, if only because of the power relations implicit in the photograph. The mouse is trapped in the bowl, whereas the boffin can presumably wander off and skitter away to do something else, in the laboratory or outside it. Lord knows what high jinks she might get up to when not making notes about a mouse in a bowl!

There is also the indubitable fact that the boffin is much, much bigger than the mouse. Humans almost always have the upper hand in any interaction with mice, simply on account of the size difference. When they are so tiny and we so huge, the matter of intellect doesn’t come into it. Even if mice were hyperintelligent, and humans dumb as oxen, we could still overpower them physically. At least, let us hope so!

Of course, both the scenarios I have outlined, the almost certainly correct one and the harebrained one, may be equally flawed. What if – it is always worth asking what if? – the object of study is the boffin herself, or her interaction with the mouse? It may be that the wire we see trailing out of the picture leads, not to some other piece of arcane laboratory equipment, but back, under the work bench, out of our sight, and is connected to the boffin. It may be, too, that the lidded bowl in which the mouse is trapped is but a miniature mousy model of a much bigger lidded bowl, in which both boffin and mouse are trapped. We may imagine similar tubes, similar wires, protruding or feeding in to this uberbowl, calibrated and monitored by higher boffins, one of whom is making notes in a ringbound notepad. Those notes might pertain to the boffin only, or to the boffin and the mouse.

There is a further possibility which scarcely bears thinking about, for it is all too terrifying. What if – again, what if? – the higher boffins are not humans but mice? Hyperintelligent mice, either gigantic ones from some far distant space age planet of hyperintelligent giant mice set on conquest of the Earth, or a teeming throng of thousands upon thousands of mouse-sized mice, whose very numbers serve to give them an advantage over puny humankind? The object of their study might be to ascertain how well, or ill, the boffin treats the mouse in its little lidded bowl. Her treatment of the mouse will determine how the invading giant space mice thereafter treat the human inhabitants of the conquered planet. Boy o boy, this is world-shuddering stuff! The fate of millions, billions, may depend on just what the boffin does next. If, having finished her notes, she removes the lid from the bowl and places in it a little excelsior for the mouse to snuggle in for a rummage and snooze, humanity may survive until the morrow. But if she cackles and pipes into the sealed bowl, through the tube, poison gas to fell the mouse, then we are doomed, doomed.

There is a personal story here, too. Did the boffin realise, when she woke up that morning, that she held the fate of humankind in her hands? No doubt such a thought was the furthest thing from her mind as she tucked into her breakfast of boffins’ vitamin-enriched poptarts. Later, as she took her white lab coat out of its locker and pulled it on, was she daydreaming of her boyfriend Dan and their imminent Alpine hiking holiday? And then . . . and then she stepped into what she thought was a common or garden laboratory but was in fact a giant lidded bowl, watched over and studied by hyperintelligent intergalactic space mice, armed with ringbound notepads!

There may be further interpretations of the picture, convincing or otherwise, which readers may wish to add in the comments. Meanwhile, I think it is up to every one of us to decode precisely what is meant by that mysterious stencil, SPEC. NO. 40642.

On Tongs

See, see? Whether it be burning coals or sugar lumps, his manipulation of the tongs is peerless. He is a dab hand. The dab, too, a demersal fish, he has plucked from the tank with the tongs, with great care, to watch it wriggle, before allowing it to plop back in, where it sinks gratefully to the sandy bottom. Coal, sugar, dab: these are but three of his tong manipulations.

He was born to it. His papa thrust the tongs into his tiny infant fist. Papa was the Shatteridge Tongsman, as his papa had been before him, and his before his, all those papas stretching back generations since first the tongs were forged on the first Shatteridge Tongsman’s legendary anvil.

The first words he could speak were the words of the Song of Tongs. At six he was sent out from Shatteridge across the desolate tarpoota, practice tongs in his satchel. He confronted bears and monkeys and wolves, and human wolves in the form of the roaming tarpoota banditti. He learned the manipulation of the tongs.

Epp, dubbed Glabb, taught him further tricks. Sweeping movements, significant passes, sleight of hand, delicacy, deftness. The wonder was that Epp, Glabb, was blind. He prowled the castle ramparts with, it was whispered, long invisible tongs. Many a flunkey felt their pinch from an inconceivable distance. Even papa was in awe of Epp, or Glabb.

It was important to watch the wrigglings of the dab with great reserves of concentration, to memorise them. They told the weather, the crop failures, the outcome of battles. Not so the manipulation of the tongs with burning coal and with sugar lumps. Those were mere humdrum manipulations, to avert blazes or to sweeten infusions. It happened that a piece of burning coal might pop from the hearth on to the carpet, if the fire had not been properly set. Far better to pluck the coal from the carpet with the tongs than to let it burn and have need of flunkies with pails and buckets to extinguish it. It happened that an infusion might be bitter or sour and barely potable without the addition of a sugar lump. Better that it be sweetened than poured unwanted down the drain.

But the dab, the dab! Epp, dubbed Glabb, was the repository of the dab’s wrigglings lore. Incapable of seeing the wrigglings, he had them reported to him. Not by the Shatteridge Tongsman, whose job was to concentrate on the manipulation of the tongs. To have to watch the dab with piercing acuity the meanwhile would be asking too much, far too much. Thus by his side was the Dabwriggleman. It was another hereditary post, passed from papa to son. As for the dab, there was a pool for them, in the castle grounds. They settled there on the sandy bottom, being dabby, until such time as the tank dab died and had to replaced. Then the Dabnetman came lumbering towards the pond with his net. He cast it about with great skill, to ensure just one dab was caught in its mesh. And then he hurried, hurried, through the grounds and in the gate and through the hall and up the stairs and along the corridor to the chamber wherein the tank rested on its stilts, and he plopped the new dab into the water, and it sank to the sandy bottom, awaiting, though of course it did not know it, the twice-daily entrance of the Shatteridge Tongsman with his tongs.

Neither the Dabwriggleman nor the Dabnetman had any doings with burning coals nor sugar lumps, save to be warmed by the fire or refreshed by the sweetened infusions. Demarcation lines were stringent in that castle.

Stringent, too, at least by name, the Stringent Tongs. This was the pop group who played in the castle ballroom and who performed the Song of Tongs, at daybreak, at lunchtime, at dusk. A basic guitar, bass, drums trio, augmented on spectacular days by glockenspiel and Ponsonby hooter. They were old hands, drawn from the village. Subject, upon entering the castle, to a stringent code of conduct. The code drawn up by Epp, dubbed Glabb, or more correctly by his papa’s papa’s papa’s papa’s papa. It may even be that further papas be added to that litany. Generations who have patrolled the ramparts with, it was whispered, long invisible tongs.

When the Stringent Tongs return to the village, on so seldom days, they carry with them moths and spiders and beetles from the castle. They release them on the desolate tarpoota, and off they flutter and scurry and creep.

*

I have no idea what that was all about, really. Best to think of it as an outpouring from an almost empty head. When one has determined to bash out a thousandish words a day, and meets a day when there is little or nothing going on within the cranium, and when one feels reluctant to resurrect pieces from the past too often, then one writes merely what one can. Fingertips tippy-tap the keyboard keys, in a flurry, then a pause, then a flurry, then a pause, then haltingly, until there is nothing left to tap. Actually, I had to correct that, I tapped out “nothing left to yap”. Perhaps that is the more appropriate word – prose like the yapping of a dog, meaningless, and deeply, deeply annoying.

On Fictional Ducks

What kind of madness is it that would prompt a person to make up a duck? This was a question I asked myself after consulting a list of fictional ducks and discovering, with something akin to terror, that it contained over one hundred and fifty non-existent ducks.

Let us allow those words to penetrate. Over one hundred and fifty non-existent ducks. That is no small number. Line them all up in a row and it would take a while to walk from one end to the other. And imagine the din if they all quacked at the same time! You would have to stuff your ears with cotton wool. But of course, they cannot be lined up and they cannot quack, because they do not exist and never have existed. They are wholly imaginary semi-aquatic beings, born in the minds of flawed humanity.

It is not that the world lacks real, flesh-and-feather-and-blood ducks. Go to any duckpond or lake and the chances are you will see more than a few ducks. You might even toss them scraps of stale bread from a brown paper bag if you are that way inclined. You might peer at distant ducks through a pair of binoculars. But it is a far cry from such innocent pursuits to unleash from within the throbbing jelly of your brain a made up duck. Yet clearly that is what has happened in the past, with a number of people, though fewer than a hundred and fifty. Tragically, some among these poor duck-haunted souls have invented more than one fictional duck..

You would think that, having made up a non-existent duck, the duck-maker would mop their brow and retire from the fray, perhaps clear their head by going on a long hiking holiday in an area of few ponds and fewer lakes. The last thing you would expect is that they would immediately set about inventing another duck. But some have done just that. Now you see why I used the word “madness”.

Our difficulty lies in trying to grasp the lineaments of a mentality that can spark the thought: “There are millions of ducks in the world, but (and? so?) I am going to make up another one!” And not only to have the thought but to act upon it. Perhaps that is the crucial distinction between mere eccentricity and full-blown madness. Casting back upon my own mental history, I wonder if it has ever occurred to me to make up a duck. I wonder, too, if that is a rather common thought, one shared by thousands if not millions of persons past and present. Yet how few of us have taken the fateful next step . . . the actual creation of a non-existent duck!

There is something of the Frankenstein about it, is there not? Derangement, delusion, and mania all focussed, horribly, on an idée fixe. But the duck-makers have no need of lightning-blasted laboratories high in castles, nor of hunchbacked assistants named Mungo, nor of the various paraphernalia ascribed to Victor Frankenstein in this or that recounting of his blasphemous doings. To make up a duck, one may need merely a pencil, or a typewriter, or some cloth accompanied by basic skills in needlework. That being so, we must not lose sight of the fact that the same mad impulse is at work, in both the crazed scientist and the creator of fictional ducks. It is an impulse to tame or control nature, to play God.

This is nowhere more evident than in the unnerving fact that the majority of fictional ducks are blessed (damned?) with the gift of human speech. And just as I am quite clear in my use of the word “madness”, so too with “unnerving”. I suspect if you were ever to come upon a real duck that, instead of quacking, spoke to you in a familiar tongue, you would be unnerved. I dreamed of such a duck once, and I woke up screaming. It was a hideous nightmare rather than a dream, but the important thing to state here is that the talking duck was the sole source of my terror. Nothing else that occurred in the night-phantasm was frightening, or gruesome, or unholy.

The scene was unremarkable, even humdrum. I was in my childhood home, the house I grew up in. My parents were there, peripherally, in that there was a sense of their presence. I entered the living room, and sat in an armchair, and looked across, and there, perched on the seat of the matching armchair, was a duck. It engaged me in conversation. At first, I felt no sense of alarm. Dream-logic was at work, and all seemed well. But as the duck continued to speak, its voice grew more grating and menacing, and it spoke of things I shudder to recall. Slowly it dawned on me that it was an evil duck, a Lucifer or Beelzebub duck, fathomless and awful in its pure unalloyed malevolence. That is when I woke up screaming. It is a nightmare I have never been able to forget.

That duck remains for me the epitome of all fictional ducks, and it is why I cannot shake the feeling that every other non-existent duck aspires to its state of sheer evil. Would that the makers of made up ducks take heed!

I have not mentioned, in the foregoing, a second category of fictional ducks, ones far more numerous than the one hundred and fifty or so given in the list. These are decoy ducks, usually carved from wood. Pinocchio-ducks, if you will. They are even more terrifying than the non-existent ducks we have already considered, but my nerves are shattered now, and I cannot bring myself to write about them until I have eased my overheated brain. But give me time, and I shall summon up the mental and moral resources to address the subject, and to explain why, whenever you encounter a decoy duck, you should be very, very afraid.

On Om

I have heard it said that by repeating the word “Om”, over and over again, for hours upon end, one can achieve a state of spiritual transcendence. The person from whom I heard this was an ancient mystic with a straggly beard who was sitting cross-legged three-quarters of the way up a mountain slope, where the air was rarefied. I was panting and out of breath and relying on my Alpenstock to keep me upright. Then all of a sudden, half hidden in the cloudy mist, I saw this fellow, his wrinkled countenance a picture of beatific bliss. Glad of the company after so many hours toiling up the mountain by myself, I slumped down next to him and we fell into conversation.

“Good day,” I said. I never say “Hello”, which is an improper form of greeting in my view, an illegitimate coinage by Thomas Edison devised from the huntsman’s cry “Tally-ho!” Look it up.

“Good day to you, sir,” replied the wrinkled ancient, “You have pierced the cloudy mist by which I am normally occluded from the eyes of ordinary mortals.”

It had never occurred to me that I might be an extraordinary mortal, and the thought was a pleasing one, so I smiled. This is not, generally speaking, a good idea, for it is my unfortunate lot that whenever I smile my face assumes the rictus cast of a maniac or a death’s head, and those who see it tend to run screaming. The ancient, however, stayed put. My smile held no terrors for him. I began to wonder if anything did.

“If what you say is true,” I ventured, “Could it be that you are one of those gnomes Rudolf Steiner writes about, invisible to the common riffraff, perceived only by those of a more elevated insight?”

“Do I look like a gnome to you?” he asked. It was not a snappish response, rather a gentle enquiry.

“I suppose not,” I said, “But as you are squatting cross-legged upon the mountain slope I cannot rightly adjudge your full height when in a standing position.”

“Rest assured I am no gnome,” he said, “I am one of the Hidden Masters of whom Madame Blavatsky wrote so eloquently.”

“Well knock me down with a feather,” I said, “But I thought you had your abode in the mountains of Tibet, whereas this is, unless I am mistaken, an Alpine peak.”

The ancient now moved for the first time since I had encountered him. He slipped one hand inside his white robe, and produced a feather, I think one plucked from a kingfisher or a heron. He waved it in front of me, and I was propelled flat on my back as if the stuffing had been knocked out of me. Gasping for breath, I sat back up and goggled at him.

“I did as you asked,” he said, “And now in return you must do as I ask.”

“What do you want me to do?” I said, between gulps for rarefied air.

“Continue up to the top of the mountain,” he said, “When you reach the summit, you will see that it is strewn with small pebbles. One among these pebbles, just one! mark you, is a mystic pebble, possession of which grants visions of realms beyond human sense to the possessor. You must find that pebble among all the other pebbles and bring it down from the mountaintop to me.”

“How will I know which is the right pebble?” I asked.

It was at this point in the conversation that he vouchsafed to me the business about repeating “Om” over and over again, for hours upon end, until I reached a state of spiritual transcendence.

“When that state is achieved,” he said, “You will be able to perceive the mystic glow of the mystic pebble. Then you must pick it up, pop it for safekeeping into your mouth, as if you were a Beckettian tramp, and suck upon it while you clamber back down the mountain.”

“Yes, oh Master!” I said, and up I went.

The air was more rarefied still at the summit, and I was gasping for breath as I collapsed on the peak next to a patch of strewn pebbles. I poked at them with my Alpenstock, wondering if I might already be spiritually advanced enough to perceive the mystic glow. After all, I had it on the highest authority that I was an extraordinary mortal who had pierced the cloudy mists which normally occluded the Hidden Master. But no particular pebble stood out from among the others, so I made myself as comfortable as possible and started to say “Om”.

“Om,” I said, “Om Om Om.”

I felt like a fool. I felt like even more of a fool when night crashed down upon the mountaintop and I was still sitting there saying “Om”. And I felt like the most foolish fool of all fools when dawn broke, and I was still sitting there, still saying “Om”, over and over again.

It has been six weeks now. I seem to be clawing my way towards a new plane of existence. I experience neither hunger nor thirst. My beard is straggly, and the sun has bleached my Alpine mountaineering garb so I appear to be wearing a white robe. My Alpenstock has been dragged away and gnawed by a venturesome mountain goat. I say “Om” and I gaze upon the pebbles, and I await spiritual transcendence.

On The Collapsed Lung Of The Tyrant

The left lung of the tyrant collapsed on the morning of the fourth. At midday, a satrap in gorgeous uniform sparkling with embedded gems appeared on the balcony to make an announcement. It was imperative, he said, reading from a hastily drafted statement, that tyrannical human pneumatics become the proper study of every citizen. By the evening, fat textbooks had been printed and bound and consignments ferried to every city and town and village and hamlet in the land.

So rapid was the response of the satraps that the textbooks were not proofread. A number of errors, many trivial but some calamitous, were thus allowed to stand. But the book bore the tyrant’s imprimatur and could not be questioned. As a result, every citizen gained a flawed understanding of tyrannical human pneumatics.

The tyrant, meanwhile, had been placed inside a nylon tent. A wheezing pump imitated the action of a working tyrannical human lung. The pump was operated by hand, in case of a loss of electrical power caused by the evil machinations of revolutionary scum. Pumpers were drawn from lists maintained by one of the satraps. They worked one hour shifts, and during their rest periods were penned in an anteroom.

By the morning of the fifth, embroidered lapel accoutrements bearing a three-coloured image of the collapsed tyrannical lung had been issued to all citizens, to be displayed on their outer tunics. In certain hotbeds, several persons were shot for failure to wear them. After execution, the left lungs were torn out of the corpses and hung on gibbets in the town squares. This had a salutary effect on the populace, even in the hotbeds.

The first public examination on tyrannical human pneumatics took place at midday on the fifth in the remote town of Sand. It was conducted orally, and tape recorded. Those gaining top marks were taken by sealed train to the capital. A gang of revolutionaries attempted a derailment of the train on the outskirts of Gorse. Brave conduct by the train conductor, and foolish felled log deployment by the scum, brought their nefarious schemes to nought. They were hanged in a barn and their left lungs torn from their corpses and burned on a bonfire by the loyal peasants of Gorse.

The tyrant was told of the narrowly averted derailment. He was as yet unable to speak, but he blinked significantly. The blinks were interpreted and converted into text by a satrap. Plans to have the text declaimed from the balcony were put on hold. It was considered best to wait until after the next day, the sixth, which was Flag Day.

On arrival in the capital, the top scoring tyrannical human pneumatics examinees were taken from the sealed train in sealed trams to the National Archives. Here they stood behind glass to watch as the tape recordings of the examinations were placed on the register and locked in a special bomb-proof cabinet. They were then given a snack in the canteen.

Late in the afternoon of the fifth, Grimes “the Wolfman”, leader of the revolutionaries, was arrested in a jungle clearing. He was spirited to the capital by way of the subterranean pulley-car system. Intelligence reports hinted that he had unparalleled expertise in human pneumatics, a field closely related to tyrannical human pneumatics. Bound in chains, he was taken to a sealed room in the palace, to where the examinees from Sand were also brought once they had digested their snacks in the National Archives canteen.

The sixth was Flag Day. The weather was such that artificial winds were needed to make the flags and standards and pennants billow. Further pumpers had to be recruited from the satrap’s list to ensure sufficient numbers for both the tyrant’s lung pump and the artificial wind contraptions. For a while it was touch and go, until a keen-eyed under-satrap found a supplementary list which had been misfiled in a filing cabinet. He was given a medal, a gorgeous disc of brass embedded with gems that sparkled in the sunshine.

Grimes “the Wolfman” was undergoing a tormented moral struggle between his revolutionary principles and his professional pride as an expert in human pneumatics. The examinees from Sand stood gazing at him with the imploring moon-eyes of calves. Some let tears roll slowly down their cheeks, but did not overdo the sobbing lest Grimes thought they were making use of freshly chopped onions behind his back. Behind a panel, certain satraps discussed the pros and cons of an amnesty for Grimes. It was a heated discussion.

On the morning of the seventh a puncture in the left lung of the tyrant was repaired and the lung was reinflated. He was fed from a bowl of slops. Several satraps were executed and their left lungs torn out and kicked through the broad boulevards of the capital by cheering citizens. Grimes shaved off his beard and was given a satrapage and a gorgeous uniform sparkling with embedded gems. A fleet of aeroplanes sprayed the jungle with defoliant. The area was then covered with cement as far as the eye could see. The examinees from Sand were appointed as tyrannical human pneumatics emergency pumping supervisors and given vouchers and bungalows. A second edition of the fat textbook was issued, with corrections. The tyrant appeared on the balcony, propped up by a concealed prop, and waved to the teeming masses.

On the morning of the eighth, the right lung of the tyrant collapsed.

On Your Favourite Forts

I was pleased to note, in this week’s newsletter from World Wide Words, that Michael Quinion turns his attention to hoity-toity. He tells us that the original meaning was “frolicsome, romping, giddy, flighty”:

Hoity-toity derives from the long-obsolete verb hoit, meaning to “indulge in riotous and noisy mirth” (have you hoited recently? it’s supposed to be very good for you) or to “romp inelegantly” (again from the OED; is it even possible to romp elegantly?). Where hoit comes from is uncertain, although an early form suggests a link with hoyden, which is now an unfashionable way to describe a noisy or energetic girl but which at the time could also mean an ignorant or clownish man. This is probably from the Middle Dutch heiden, a heath, hence a yokel; if so, hoyden is a close relative of heathen.

Curiously, the estimable Mr Quinion has nothing to say about Fort Hoity and Fort Toity, the favourite forts of Hooting Yard readers. In fact, other than a few military history buffs and Uncle Tobys, you lot may be the only persons who actually have favourite forts. I conducted a sort of straw poll on this matter by buttonholing a random selection of pedestrians between here and Nameless Pond.

“Excuse me,” I said, standing in front of them so they could not pass, “May I ask you which is your favourite fort?” I did not get a single coherent or sensible answer. Perhaps had I armed myself with a clipboard and a biro and a high visibility jacket the results would have been different. But on the evidence of my admittedly unscientific survey, I am forced to conclude that one hundred percent of riffraff infesting the streets of my bailiwick early on a Saturday morning care not a jot for forts of any kind. Some of them seemed not to know what in heaven’s name I was talking about. That is the modern education system for you.

As fanatically devoted Hooting Yard readers, you already knew, or at least suspected, that you were members of a select band. Now you have further confirmation, in that you can most definitely claim to be among that minuscule portion of the populace who have a favourite fort. My research, such as it is, tells me that you are pretty evenly divided between Fort Hoity fans and aficionados of Fort Toity. I have not analysed the stats in great detail, partly because there aren’t really any reliable stats on this matter, and partly because, even if there were, I doubt that I am capable of the drudgery necessary to analyse them. I have better things to do with my time, such as smoking and staring out of the window at crows while listening to Essay On Pigs by Hans Werner Henze. It’s a godawful racket, but it drowns out the sound of the neighbouring tinies, whose screeching would otherwise unhinge me.

Over the years, several readers have asked me to give a clear and highly amusing account of the differences between Fort Hoity and Fort Toity. I suspect that such requests are based not on any genuine keenness to be able to tell the forts apart as much as a desire to have some justification for plumping for one fort over the other. It is, after all, a mark of the truly ‘with-it’ Hooting Yardist that they care enough to choose Fort Hoity over Fort Toity, or, of course, Fort Toity over Fort Hoity. Nobody wants to admit to not giving a hoot one way or the other, as if they were the riffraff in the vicinity of Nameless Pond.

But while it is easy enough to cry “Fort Hoity!” or “Fort Toity!” when asked which is your favourite fort, far more difficult is the supplementary question, “Why?” Personally, I never ask that myself. I never wish to entangle my readers in potentially brain-numbing mental gorse bushes. As far as I am concerned, it is enough that each of you has a favourite fort. But great heavens to Betsy, some of the tales I have heard from Hooting Yard picnics and charabanc outings and mass singalongs, indeed from any occasion where two or more Hooting Yard readers gather together! Here is one such tale, related in a letter received from one T. Thurn:

Oh wondrous and resplendent Mr Key!

I wish to tell you about an incident that occurred at a recent Hooting Yard outing. A quartet of us had gone on an otter rescue mission, but the circumstances in themselves are not important. When we were still some distance from the riverbank, one of my companions asked me which was my favourite fort, Fort Hoity or Fort Toity? “Fort Toity”, I replied. Then she dropped a bombshell. “Why?” she asked. I realised I was quite unable to answer the question, as I have no idea of the difference between the two forts, other than a vague inkling that Fort Toity is a bit smaller then Fort Hoity. I was forced to dissemble. I pointed at the sky and yelled “Look!”, hoping there would be a flock of some kind of birds visible. Alas, it was one of those birdless days, so I had to pretend I had spotted unusual patterns of light and shadow presaging the collapse and ruination of the empyrean realms. I got away with it this time, but I would be grateful if you could provide a clear and highly amusing account of the differences between Fort Hoity and Fort Toity so that, next time I am asked, I will be able to justify my plumping.

Yours frolicsome, romping, giddy, and flighty,

T. Thurn xxxx

Must I do all the work? If T. Thurn had any strength of character he would refrain from bothering me with his tiresome whinges. I have gaspers to smoke and crows to watch and combative Teutonic din to listen to! It would be a simple enough matter for any true devotee to read through the collected Fort Hoity and Fort Toity references and to compile their own list of plumping reasons. That should keep you lot occupied until the morrow.

On Astrology

Eight years and one month ago, I posted the following horoscope here at Hooting Yard:

Our horoscopes are based on the so-called Blodgett Astrological System of six, rather than twelve, signs. Over many years, forecasts made under this system have proved over eight hundred and forty-eight times more reliable than all that Pisces and Aquarius nonsense! You can work out which sign you are by referring to the absolutely splendid up to date online guide at www.blodgettglobaldomination.com/humanfate.html (site under construction).

Fruitbat. Try to remember that you are lactose-intolerant. The hours before twilight will be significant for your pet stoat. Throw away that tub of swarfega.

Mayonnaise. It is time to dig out your copy of Gordon “Sting” Sumner’s profound I Hope The Russians Love Their Children Too and play it again after all these years. You may overhear the phrase “going postal” more than once this afternoon. Pay special attention to patches of bracken.

Coathanger. Your recurrent nightmares about an albino hen will finally make sense. Don’t go near any buildings, large or small.

Slot. At last your destiny will begin to unfold, probably as you take a stroll along the towpath of the old canal. Vengeful thoughts will assail your brain, but you should ignore them, and devote your energies to making jam. A hollyhock may have special meaning for your kith and kin.

Tarboosh. O what can ail thee, horoscope reader, alone and palely loitering? Make sure you treat yourself to an electric bath and a session in a sensory deprivation tank. The Bale of Gas in your House of Stupidity has incalculable effects. You will stand on the steps of the Insane Asylum, and hundreds of men and women will stand below you, with their upturned faces. Among them will be old men crushed by sorrow, and old men ruined by vice; aged women with faces that seemed to plead for pity, women that make you shrink from their unwomanly gaze; lion-like young men, made for heroes but caught in the devil’s trap and changed into beasts; and boys whose looks show that sin has already stamped them with its foul insignia, and burned into their souls the shame which is to be one of the elements of its eternal punishment. A less impressible person than you would feel moved at the sight of that throng of bruised and broken creatures. A hymn will be read, and when the preachers strike up an old tune, voice after voice will join in the melody until it swells into a mighty volume of sacred song. You will notice that the faces of many are wet with tears, and there will be an indescribable pathos in their voices. The pitying God, amid the rapturous hallelujahs of the heavenly hosts, shall bend to listen to the music of these broken harps.

Nixon. Vile dribbling goblins covered in boils will make life difficult today.

Why am I returning to this old horoscope today?, you may ask. Well, for eight years I have been ignoring a cardboard box full of letters which I received in the days after this postage appeared. The box – or rather its contents – gnawed at my conscience. Gnaw, gnaw, gnaw. I have had a terrible time. If you have ever felt reproached by sight of a cardboard box, you will understand what I have been going through. That is why I hid the box in a cubby and buried it beneath a pile of rags and locked the cubby and took a bus to the seaside and hurled the key as far as I could into the broiling ocean. I thought, by doing so, I could put those letters out of mind. How could I be so naïve?

After a near decade of mental turmoil, yesterday I called a locksmith and asked him to fashion a fresh key for the cubby. With commendable honesty, given that he was turning down my custom, he pointed out that the cubby door was of so flimsy a nature that even a puny person could bash it open as easily as smashing an egg. Watch, he said. And he gave the door a thump and it fell to bits and there was the pile or rags and, beneath, the cardboard box, and, in the box, the letters.

I plucked from the box the first one that came to hand, and read it. Eight years had passed, but I remembered every word.

Dear Mr Key

I am writing to complain about the horoscope you posted at Hooting Yard yesterday. I was born under the sign of Coathanger, so I was fully expecting my nightmares about an albino hen to make some sort of sense. I so arranged things that I spent the day in an eerie blasted landscape of marshes and moorland, far, oh so far, from any buildings. I awaited revelation, but revelation came there none. I can only conclude that your so-called horoscope is a piece of piffle. You have ruined my life. I am going to take my case to the Astrological Courts, and you will be prosecuted, and all your stars will be blotted out, forever!

Yours vengefully,

Tim Thurn

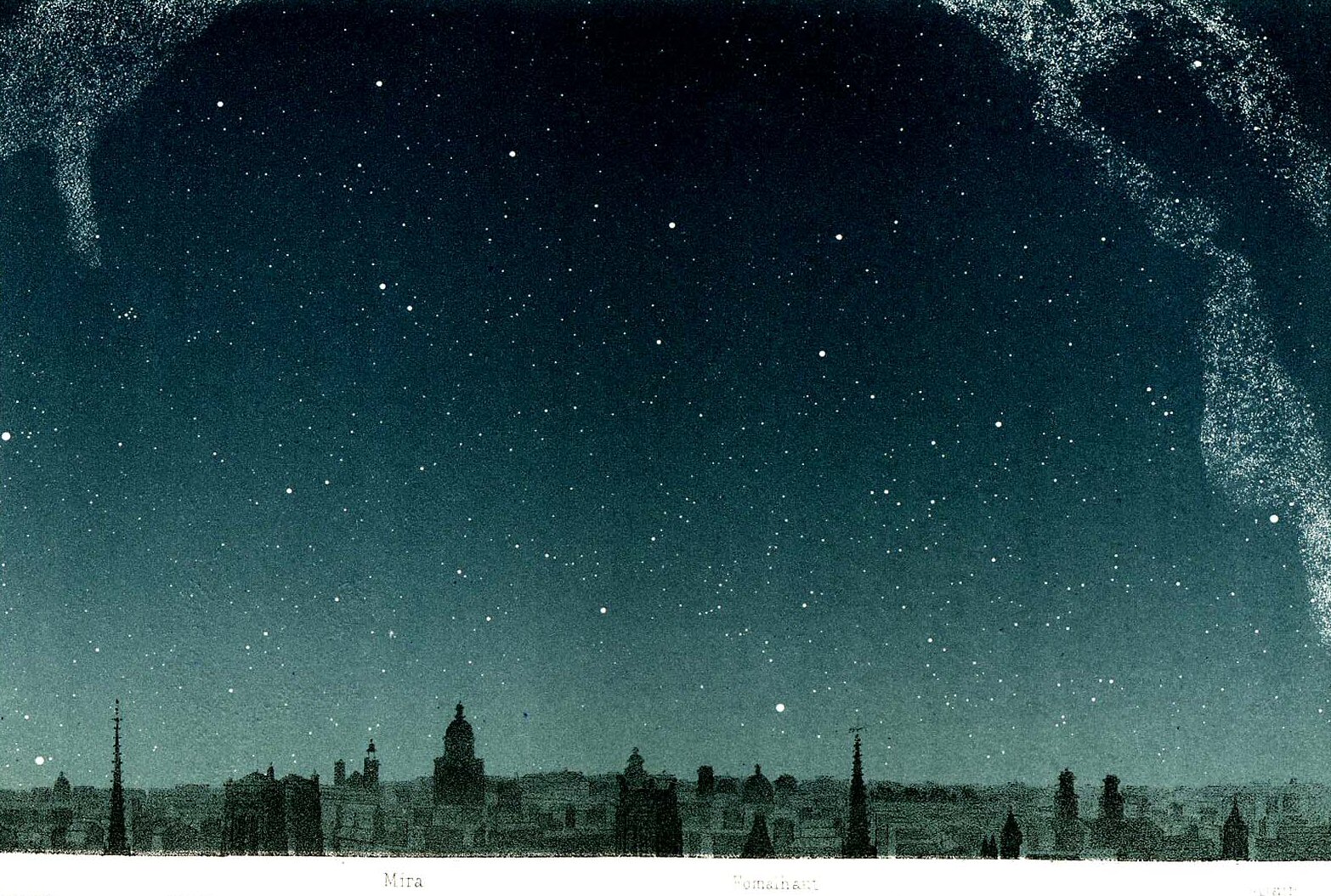

All the other letters were similar. Complaints, gnashing of teeth, rending of garments, rage, threats. Some were written in the blood of ducks, never a good sign – and I use the word “sign” significantly. I never responded to a single one of these missives. I thought I was in the clear. I did not know how grindingly slowly the Astrological Courts worked. But yesterday their judgement arrived, in the form of a peculiar light in the sky and a distant booming, as of a foghorn or perhaps a bittern. And when night fell, I cast my gaze upwards, as I always do, and the sky was empty of stars.

I still believe I did no wrong. I blame Blodgett. I shall appeal to the Astrological Courts, and hope for some shred of mercy in the sublunary world.

On Blodgett’s Jihad

Given the latest act of lethal stupidity by the homicidal barbarian community, it seemed timely to repost this piece, which first appeared exactly six years ago today.

Bad Blodgett! One Tuesday in spring, he went a-roaming among the Perspex Caves of Lamont, part of that magnificent artificial coastline immortalised in mezzotints by the mezzotintist Rex Tint. Sheltering in one of the caves from a sudden downpour, Blodgett took his sketchbook out of his satchel and passed the time making a series of cartoon drawings of historical figures. The pictures were imaginary likenesses, of course, for Blodgett was ignorant of many things, and he had no idea what Blind Jack of Knaresborough looked like. Nor was he at all sure that his double cartoon of Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray bore any resemblance to the stars of Double Indemnity. The rain showed no sign of ceasing, so Blodgett filled page after page, scribbling drawings of Marcus Aurelius, Christopher Smart, Mary Baker Eddy, Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley, and the Prophet Mohammed, among others. It was this last cartoon that caused ructions which were to have so decisive an effect on Blodgett’s life.

Later that day, on his way home from the Perspex Caves of Lamont, Blodgett inadvertently left his sketchbook on the bus. A week or so later, a bus company employee was checking through the lost property and took a few moments to leaf through the book. Turning the fateful page, this employee – an adherent of the Islamic faith – was by turns outraged, humiliated, mortally offended and infuriated when he saw Blodgett’s cartoon. As is the way with such matters, he immediately arranged for copies to be distributed to mullahs and imams around the world, so that they too could share his outrage, humiliation, mortal offence and fury. Soon there were calls for Blodgett to be beheaded or otherwise put to death, and he went into hiding. Let’s take a look at the picture, so that we can understand what all the fuss was about.

(In an interesting side note, there was a similar flurryof anger from a sect devoted to the cult of Fred MacMurray, but this fizzled out after Blodgett pledged to attend a penitential screening of one of the actor’s late pieces of Disney pap.)

Meanwhile, hiding out in the Perspex Caves of Lamont, the evil cartoonist had time to think through what had happened. Blodgett was aware that the Victorian atheist Charles Bradlaugh had described the Christian Gospels as being “concocted by illiterate half-starved visionaries in some dark corner of a Graeco-Syrian slum”, and he did not think it much of a leap to conclude that the Prophet Mohammed was an equally deluded soul, although perhaps a better-organised one, with access to weaponry which enabled him to spread his message faster and more efficiently.

Around this time, Blodgett received through an intermediary an offer from the furious and offended Islamists. The sentence of death could be rescinded, they suggested, if he made a sincere conversion to their faith and promised to live out the rest of his days in submission to Allah. Blodgett considered this for about forty seconds before rejecting it. Apart from anything else, he reasoned, it was very unlikely that Mrs Blodgett would agree to spend the rest of her life cocooned in a person-sized tent and to stop going out by herself.

Shortly after this, still in hiding, Blodgett had a brainwave. Indeed, he became somewhat furious and offended himself. The conversion offer, he decided, was an example of the old cliché “If you can’t beat them, join them”. Well… he would join them, but not in the way they thought. If half-starved visionaries could propagate the Christian gospels, and Mohammed could claim to have heard the voice of God, as so many others down the centuries had insisted, with varying degrees of success, that they were in direct contact with supernatural powers, what was to stop Blodgett announcing that he, and only he, had found the true path? From this spark of inspiration was Blodgettism born.

He began to make clandestine visits to the municipal library at Blister Lane, devouring, among other works, the Qu’ran, the Bible, the collected works of L Ron Hubbard and David Icke, the Book of Mormon, sacred texts from all the major religions and many of the minor ones, even a couple of novels by Ayn Rand. After a few weeks of constant reading, Blodgett set out to define Blodgettism. He did not want it to be a synthesis of every other faith – that seemed a little too pat, a little too Blavatskyesque – and nor did he want it to be simply an amalgam of the good bits. Considering that he was still under sentence of death from a number of shouting men with beards, Blodgett wanted Blodgettism to be a faith at once as rigorous and intransigent as Islam. Thus, he cast aside with reluctance some of the more amusing things he had learned, such as underwear regulations in Mormonism, and Mr Hubbard’s intergalactic drivel, and fixed his attention on jihad. As far as jihad-as-inner-struggle was concerned, Blodgett could not give a hoot. But jihad-as-holy-war appealed to him as a way of taking on his persecutors, and thus became the most important feature of the Blodgettist religion.

In The Book Of Blodgett, published in paperback the following year, it has to be said that the founder of the new religion makes an impeccably reasonable argument in favour of his faith. Having devised a set of laws – called Blodgettia – he announces that it is the duty of everyone on earth to obey them, or be killed. Taking his cue mainly from the Qu’ran and the Old Testament, Blodgett devised an appropriately illogical and arbitrary set of regulations for human behaviour. The list of laws is too long and abstruse to reproduce here, but a couple of examples will suffice.

Blodgettia Law Number 12. Thou shalt not eat plums within ten yards of a pig or a goat or a starling. Those that disobey this law will be bundled up in sacking and thrown into a canal.

Blodgettia Law Number 49. It is forbidden to wear your hat at other than a jaunty angle. See appendix for diagrams of angles of jauntiness and non-jauntiness. Officials of the Committee For The Promotion Of Blodgettian Virtue And The Wholesale Suppression Of Blodgettian Vice And Abomination, armed with protractors and tape measures, will fan out across the land, and where they find hats worn at non-jaunty angles they shall proceed to poke malefactors with pointy sticks before putting them to an entirely justifiable death.

Of course, the Prophet Mohammed – let’s just take a look at that picture again, to remind ourselves –

As I was saying, the Prophet Mohammed was able to spread his word through a combination of historical and geographic circumstance and violence. Alas, Blodgettism never really took root, numbering perhaps only three or four devotees at its height, including Blodgett himself. But there are a few copies of The Book Of Blodgett which have not been pulped or thrown into dustbins, and they may yet inspire a new generation of fanatical adherents, who will demand, in big shouty voices, that they are right and every one else is wrong, and get very upset and angry if you disagree with them, and it will be your fault if they decide to blow you up or chop off your head. Be warned.

On Marshmallow Art

Startlingly hirsute Italian artist Accurso Git unveiled his latest work at the Pointy Town Biennale this week. Egregore is an anatomically accurate facsimile of the brain, rendered in Git’s favourite medium, marshmallow. Intriguingly, the startlingly untidy artist has chosen to express the concept of the egregore – an occult concept representing a “thoughtform” or “collective group mind”, an autonomous psychic entity – with a marshmallow model not of the human brain, but that of the lobster.

The students of lobsterdom among you will know that the brain of a lobster is about the size of the tip of a ballpoint pen. They do not possess the keenest intellects in the animal kingdom. Asked why his brain was so tiny, Accurso Git initially misconstrued the question and set about his interviewer with his fists, those startlingly hairy fists, with the result that the interview had to be postponed for a month while the interviewer received hospital treatment. During this time, the startlingly ill-tempered artist was given several written assurances that the tiny brain being referred to was that of the lobster, not the one encased in his own startlingly enormous head. When he was eventually placated, and the interview resumed, in a clinic annexe where the interviewer was learning to walk and talk again, Git gave this reply:

“Have you seen the cost of marshmallows? Add together the prices of sugar and corn syrup and water and gelatin that has been softened in hot water and dextrose and vanilla flavourings, take into account the optional use of colouring agents and/or eggs, tack on the labour involved in whipping the mixture to a spongy consistency, and it will be clear even to a simpleton that a startlingly impoverished artist like me, the critically acclaimed Accurso Git, could not afford more than a tiny, tiny amount of marshmallow. What little money I have must be kept aside for gourmet meals and wine and international jetset travel and floozies and pipe tobacco and a place at the table in the tiptop casinos! Yet as I struggled to bring to birth my vision, I realised that a tiny lobster-brain-sized marshmallow facsimile brain was the perfect realisation of the egregore. Were it the size of a human brain, it would be too big. Were it smaller than a lobster brain, it would be as near as dammit invisible. By settling upon the size I did I have proved yet again that I am the greatest artist of this or any other age.”

This kind of talk is par for the course with the startlingly egotistical artist, and is difficult to argue with unless one wishes to end up in hospital alongside others who have crossed him. And in truth, he has a point. When one spends many hours in contemplation of Egregore, as I have done, the sheer artistic force of the piece becomes clear. To a layman it might look like nothing more than a singularly tiny marshmallow placed upon a plinth with a glass case surrounding it, the sole object in the startlingly vast galeria of the Pointy Town Civic Hall, Scout Hut, & Temporary Allotment Rental Office. Yet, as so often, the layman does not see what the piercing acuity of the goatee’d, cravat-wearing art critic sees. Admittedly, I too was at first deluded into thinking it was a mere miniature marshmallow brain. In fact I stomped off to the galeria canteen and unleashed my laptop and, over a startlingly ungenerous helping of sausages ‘n’ pickle, I tapped out an article in which I suggested that Accurso Git had lost his mojo.

Where, I asked, were the signs of the majestic genius whose rendering in marshmallow of the Tet Offensive had been at once so offensive and so thick with sugar and corn syrup and water and gelatin that had been softened in hot water and dextrose and vanilla flavourings and colouring agents and eggs? And where oh where was the startlingly combative artist whose marshmallow Noli me tangere somehow cast two millennia of Christian art into the dustbin of history?

The answer was that he was standing right behind me in the canteen, breathing down my neck and with his fists, those startlingly bony fists, raised ready to strike. I did what any goatee’d cravat-wearing art critic would have done in the circumstances, and offered him a spoonful of pickle. While he was engaged in munching it, with his startlingly awful table manners, I had time to reassess Egregore. I continued to reassess it until Accurso Git dropped his fists, sat down, and called to the waiter for a bottle of wine and an ashtray and a floozie. Until, that is, he appeared to be relaxing, and no longer startlingly combative. I then gave him what was left of my sausage, for in all honesty I had lost my appetite.

What I have not lost my appetite for is Egregore. To that end, I obtained a special permit to set up a camp bed in the galeria, and I now spend all day, every day, gazing, with my customary piercing acuity, at a tiny model of a lobster brain fashioned from sugar and corn syrup and water and gelatin that has been softened in hot water and dextrose and vanilla flavourings and colouring agents and eggs, then whipped to a spongy consistency by marshmallow technicians, more than ever convinced that what I am gazing at is beyond any doubt the very finest tiny model of a lobster brain fashioned from sugar and corn syrup and water and gelatin that has been softened in hot water and dextrose and vanilla flavourings and colouring agents and eggs, then whipped to a spongy consistency by marshmallow technicians in the entire history of Western, or indeed any other, art. And that is my considered opinion as a goatee’d, cravat wearing art critic sans pareil.

On Out Of Print Non-Pamphlets

A while ago I waxed nostalgic about the Malice Aforethought Press, Mr Key’s early adventure in small press publishing. Now I have recalled, out of the blue, that back in the benighted 1970s, when I was but a teenperson, I embarked on a similar, even more amateurish, project. I do not know what has suddenly brought this to mind, but I thought it might be of some passing interest to the fanatical devotees among you lot.

‘Twas in the year 1978 that I turned my attentions to what at the time I thought was “proper writing”. The first fruit of this was a piece called Jonathan Owl-Catcher, which as far as I recall was based on an original idea, as they say, by my pal Carlos Ortega. In the interests of clarity I should point out that this was not the Venezuelan union and political leader of the same name, nor any relation to Daniel Ortega, the President of Nicaragua. Having mentioned the title, I must now confess that I remember nothing else about this story whatsoever.

It was with the second piece written at this time that I had the bright idea of publication. Remember these were the heady days of punk and the DIY aesthetic pioneered by the splendid Desperate Bicycles. Having written Uncle Harold Swats At A Moth With A Broom-Handle And Lives To Tell The Tale, what I ought to have done was (a) said to myself “Lord God Almighty, that is an unwieldy and awful title”, and (b) torn it to shreds and stuffed the shreds into a burning fiery furnace.

Instead, I somehow convinced myself that there was a market for this juvenilia, and I proceeded to storm it. My storming was distinctly ill-conceived and inept. I did not even bother to make the story into a pamphlet. I simply photocopied it and fixed the four or five pages together with a staple in the top left corner. At least it was typewritten rather than done by hand.

I now had to sell the thing, so I decided to place an advertisement. There was at the time a monthly magazine called Vole, an early organ of the ecowanker tendency. Actually it was a far better publication than that makes it sound, edited as it was by the late Richard Boston. Boston was a Grauniad journalist whose writing was both witty and learned. His 1976 book about the British pub, Beer And Skittles, was a sort of Bible for my elder brother, and I shall always remember a newspaper piece he wrote about the prep school teacher recruitment agency Gabbitas & Thring. Until I read that, I thought the pair had sprung fully-formed from the mind of Ronald Searle.

I was a keen if naïve reader of Vole, so I reasoned that all its other readers would be deeply fascinated by my fiction. Accordingly, I placed an ad in the classifieds, offering my story for sale by mail order. As I had to pay by wordage, and the title was so wretchedly long, I think the entire text of the ad amounted to little more than the title, followed by “short story”, followed by my name and postal address. Yes, children, that was the kind of thing we did in the days before Het Internet.

Remarkably, it seems to me now, I received about five replies. One of these people even wrote back, offering words of encouragement. I wish I could remember his name. He was, now I think of it, the first person outside my immediate family and friends, who ever read a word of mine. Good God! He might even be reading this, now! If so, please get in touch. On the other hand, given the passage of time, it might be a case of R.I.P. Nameless or not, ye shall be remembered.

Duly encouraged, I bashed out another story, The Bassoon Recital. I used the proceeds from my five sales to pay for an advert, again in Vole, for this new piece. (I think – I hope – I sent my mentor a free copy.) It was less successful than the first, selling perhaps two, or it might have been three. But fewer, fewer.

Interestingly, no alternative approach occurred to me. As I am sure you are shouting, I could have, for example, waited until I had written a handful of pieces and cobbled them into a proper pamphlet. Or I could have submitted them to magazines. And if I must insist on trying to sell stapled sheets of A4 to punters, I could at least have advertised them elsewhere. But no. By the time I wrote the last piece, On The Quayside, I had become discouraged, and I do not recall advertising it at all.

So what became of them, these masterworks? It is possible, if I rummaged sufficiently, that I might find a yellowing dog-eared copy mouldering at the bottom of a cardboard box in a cupboard. I may indeed make such a rummage. In the meantime, I will tell you what I remember.

The “plot”, if we can dignify it with that word, of Uncle Harold Swats At A Moth With A Broom-Handle And Lives To Tell The Tale is given in the title. I don’t think anything else actually happens.

The Bassoon Recital would be more interesting, influenced as it was by Edward Gorey. Unfortunately that is about all I can recall.

Of the three, I think On The Quayside is the one I would be least embarrassed to post here at Hooting Yard, were I to fall upon it while rummaging. I remember that the text was deliberately laid out so each paragraph consisted of a single sentence. I remember that the tale involved a crate being hoisted off a ship on to a quayside, and a stevedore taking charge of it, and discovering that within the crate was a demented ostrich. I think the whole thing took place in what we might call Hooting Yardy weather, that is, rain, mist, gales.

And after that, silence, until a few years later, when the Malice Aforethought Press was brought howling into the world, and the first vague outlines of Hooting Yard could be discerned.

On Being Hopelessly Lost

A letter arrives:

Dear, beloved Mr Key

We are lost, hopelessly hopelessly hopelessly lost. We write “hopelessly” thrice to indicate that each of us is hopeless. We would not have you think one is hopeless while two retain hope, nor that two are hopeless and one still hopeful. We are all hopeless and we are all lost.

How we have come to this pass may take some explaining. We got off the bus, as you told us. We were on a lane. There was a hedge. There may have been birds nesting in the hedge. There was certainly sign of nest, if not of bird. Had a bird returned to the nest while we stood there in the lane as the bus chugged away into the distance, there is every chance we might have killed the bird for food. We were famished. Lucky bird, then, that it was off and out, somewhere in the sky, in flight.

We peered over the hedge. There was a field. It was an extensive field containing several cows. We pondered killing one of the cows for food but could not come up with a method. Had there been a bird in the nest in the hedge, we could have borne down upon it, the three of us, menacingly, and made short work of it. Two could hold it still while the third throttled it. We looked at a cow and tried to picture applying that same method. It was not a convincing picture.

We cast our six eyes around in case there might be a pile of rocks in the field or beside the lane. With a rock of sufficient size we thought one of us might bash the cow about the head until it dropped dead. But look as we might there seemed to be nothing bigger than a stone or a pebble, neither of which we thought would prove fatal to a cow no matter how hard we hit it. We had to bear in mind the presence of several cows and assume that the ones we did not attack would come rushing to the aid of the one we did. A few quick sharp blows with a big rock would kill a cow before the other cows came a-charging. But we would have no such window of opportunity armed with mere pebbles. We dismissed the cows as a possible source of food and turned our attentions back to the lane.

We were famished, but at this stage we were not yet hopeless, nor indeed lost. After all, we had only just alighted from the bus and had not yet had time to get our bearings. In our hearts there was a flicker of optimism that within a few hundred yards we might come upon the orchard with its squirrels, or the hotel, or both. We decided to walk along the lane in the same direction in which the bus had travelled. The bus itself had disappeared over the horizon. Ahead of us we could see various clumps and slopes and distant buildings. Hence our hope.

Shortly afterwards, we came upon a puddle of recent rainwater. We fell upon our knees and drank our fill. It was a big puddle, so we did not drain it. We spotted in it a small pale, almost translucent, writhing wriggling wormy maggoty kind of being. Food! We could have compared notes on whose famishment was most debilitating, or drawn lots, but instead, and in spite of its tininess, having plucked it from the puddle we chopped it into three equal portions. Squatting beside the puddle, we then sucked on our helping rather than bolting it down, to eke from it all the nourishment we could and to make it last as long as possible. Yum!

Thus fortified, if only minimally, we toiled on along the lane. Certain clumps and slopes and distant buildings grew closer. None was yet close enough to ascertain whether an orchard or hotel was among them. Pangs of thirst now beset us, as the wormy maggoty thing had proved surprisingly salty. We encountered no further puddles, but then the hedge beside the lane came to a sudden stop and in its place was a ditch. In the ditch was a great deal of water, an admixture of recent rain and some kind of filthy muck-riddled brownish liquid oozing up from below. We judged that were we to drink it, we would be at risk of stomach cramps and digestive horrors and many another gastric malady. “Gastric” may not be the appropriate word, but let it stand. So we trudged on, the watery ditch alongside us like a cruel taunt of the devil’s. It may have been about this time we began to lose hope. But we were still not lost, because we could see the clumps and slopes and distant buildings ahead. We had something to aim towards, be it but a chimera.

But then a mist descended. It was a thick mist. We could not even see our hands in front of our faces, let alone the clumps and slopes and distant buildings. There was some relief in the fact that moisture was present in the mist, so if we gulped mouthfuls of it and swallowed, our thirst raged a little less, oh a little less, but enough, enough. If you can put yourself in the place of a famished and thirst-ravaged orphan recently discharged from an orphanage and sent into the rustic wastelands on a fact checking mission by a writer of unparalleled genius, accompanied by two similarly discharged and famished and thirst-ravaged orphans from the same orphanage on the same fact checking mission, you will appreciate how greedily we gulped that mist-moisture.

In fact, we were so revitalised that we said “Pshaw!” to the mist, the three of us in unison, and we blundered onwards, even though we could not see where we were going. This was our undoing. For when the mist cleared, as suddenly as it had descended, there was no sign of the clumps and the slopes and the distant buildings. There was merely a bleak expanse of nothingness. We were lost. And we were hopelessly hopelessly hopelessly lost.

We slumped against a blob of the nothingness that might have been a vestige of hedge or of the side of a ditch. We sobbed quietly for a while. Then we wrote this report. It is an interim report. Hopeless we may be, thrice hopeless, but we shall press on with our mission, as if it were a metaphor for man’s life upon this mortal coil. If you receive this letter, you will know that at least we stumbled upon a postbox. What the postbox is a metaphor for, we leave for you to judge.

Yours lost and hopeless, your devoted fact checking team.

Bim, Bam and Little Nitty

On Fact Checking

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again : reportage is the lifeblood of Hooting Yard. The reason I say it again is to drum it into your heads. There is a distressing number of readers who seem to believe that I make all of this stuff up. Quite apart from the sheer foolishness of doing so, I am ever mindful of B. S. Johnson’s dictum “Telling stories is telling lies”. And, as Lennox and Stewart put it so cogently, “Would I lie to you?” You need not attempt to answer that now, just read on, mes braves!

To bolster Hooting Yard’s reputation as a respectable space age information provider, I have decided to appoint a Fact Check Team. They will go about their business independently, without fear or favour, digging and rummaging and fossicking where their piercingly-honed instincts take them. If it should so happen that they come upon an instance of inaccuracy or outright lying, I will accept their ruling and remove the offending postage, replacing it with a correction written by the team. I will even so arrange things that the correction appears in big bright red bold capital letters, accompanied perhaps by a skull-and-crossbones symbol such as one sometimes finds on bottles of poison. That should liven things up!

So let me introduce you to the team. There are three members, each of whom graduated, if that is the word I want, from Pang Hill Orphanage. Bim and Bam and Little Nitty each have long experience of the kind of painstaking drudgery necessary to hunt down the facts, although in their case the painstaking drudgery they experienced was sewing mailbags in a dank cellar by the light of a single Toc H lamp. I have always been a great believer in transferable skills.

I am also a great believer in the benefits of fresh air and hiking and long jaunts in the open air. That is why Bim and Bam and Little Nitty will do their fact-checking in “the field” or “on the ground”, out and about. In any case, I do not want them cluttering up my chalet o’ prose and whimpering and eating me out of house and home. They can forage for nuts and berries and fresh puddlewater when they are in the field or on the ground.

In order to decide what the trio should investigate first, I conducted a lightning readers’ poll. “On what topic,” I asked, “can Bim and Bam and Little Nitty cut their chops as a tiptop fact check team?” Typical of the response I received – sorry, I mean to say “responses” plural, because I did ask more than one reader, honestly, cross my heart and hope to ascend in glory to the ethereal realms – was this, from one T. Thurn:

Dear Mr Key,

Last night I lay awake tossing and turning and biting and pummelling my Plumpo!™ pillow, bereft of even a second of shut-eye because I am so desperate to know if the orchard and hotel and squirrels referred to in Alfred Pigtosser’s autobiography I, Alfred Pigtosser actually exist. And if they do, I have supplementary questions, not so much about the squirrels but regarding the orchard and hotel. They can wait, however, until Bim and Bam and Little Nitty have ascertained the brute reality or otherwise of the orchard and the hotel and the squirrels and reported back, exhausted from their hike or jaunt, having cut their chops.

Yours with bated but minty breath,

T. Thurn

I think you would have liked the next scene. “Bim! Bam! Little Nitty!” I called, in my most stentorian boom. They shuffled in, spindly and unkempt and dribbling. Terry-Thomas would have dismissed them as an absolute shower!, but I had every confidence in my fact check team. “Here,” I said, “Take these three partly prepaid bus tickets, go to the bus stop, and wait for a bus. When eventually a bus arrives, board it and take it as far out into the countryside as it goes. Then ring the bell and alight and go in search of the orchard and hotel and squirrels mentioned in Alfred Pigtosser’s autobiography I, Alfred Pigtosser. And don’t get up to any mischief or it’s back to Pang Hill Orphanage with you!”

“Please Mr Key,” whimpered one of them, Bim or Bam or Little Nitty, in a weak thin quavering voice, “How are we to survive in the countryside when we are used to being given a bowl of gruel once a day at grueltime?”

I gave each of them a hefty slap on the back and boomed “Fear not! The Lord will provide! And if He does not, because your prayers are insufficiently abject, then I am sure you will find opportunities to forage for nuts and berries and fresh puddlewater! Now off you go, before I summon the beadle to drag you back to the orphanage!”

The last I saw of them, they were trudging disconsolately to the bus stop. I have no doubt, however, that at this very moment they are far away on some bleak blasted heath or moor, their vitals stimulated by all that unaccustomed fresh air, diligently seeking signs of an orchard and a hotel and some squirrels. As soon as they report back, assuming they can cobble together the bus fares for the return journey, I will let you know. And I will publish their report in full. It will, I am sure, confirm the existence of that orchard and that hotel and those squirrels. Then T. Thurn can fire at me as many supplementary questions as he likes.

On I, Alfred Pigtosser

Before we can begin to address today’s topic, there is a matter of potential brain-numbing confusion which I think it best to clear up. If I neglect to do so, there is a risk that at least some of you lot will become bewildered, and that is in nobody’s interest. As I hope you realise, I strive to make things as clear as I can. In spite of my weakness for passages of purple prose, or for using dozens of words where a handful would do, or indeed for making up words entirely, I am always mindful of the need for clarity. So, yes, my prose could be plainer, but I want you to appreciate that I am never deliberately obfuscatory. Well, rarely. And it could be argued that from time to time you lot need to have your brains jangled about, and who better to jangle them than Mr Key? Answer me that, if you dare.

But today is not a jangly type of day. It is a day for crystal clarity, the sort one might see through a recently wiped window, especially if one remembered to put one’s specs on. I always remember my specs, I jam them on when waking and remove them when I retire. Without them I would be stumbling about in a haze. But we are not here to discuss my opia. Sorry, I mean my myopia. Our subject today is the bestselling autobiography I, Alfred Pigtosser.

Straight away, you see, the source of potential confusion whacks us in the face. At least, it does for those of you who read Hooting Yard diligently and daily. Yesterday, you will recall, we made mention of one I. Alfred Pigtosser, the possibly pseudonymous writer of letters to Miss Blossom Partridge’s Weekly Digest. That Pigtosser, whomsoever he may be, is no relation to the Alfred Pigtosser who wrote I, Alfred Pigtosser. You can spot the difference because the autobiographer’s first name is Alfred, whereas the mad letter-writer’s first name is something beginning with I. What it might be we do not know. Isambard or Ignatz, perhaps. But let us not dwell upon it, for we would soon be embroiled in a Rumpelstiltskinny situation, never a happy prospect.

I think I have now made it plain, as plain as the peas on my fork, that I. Alfred Pigtosser and Alfred Pigtosser are two different persons. That is the task I set out to accomplish in my opening paragraph, and I think we can all agree that I have succeeded brilliantly. If there remains, among you lot, anybody who is still confused, I would suggest the fault lies with you rather than with me. You might want to go and get your head examined by some sort of specialist in dimwits.

Let me take the rest of you by the arm and guide you into the world of Alfred Pigtosser, or at least the world as revealed to us in his autobiography. It has been a rather surprising bestseller, particularly when one considers the photograph of the author staring out at us from the front cover. Seldom have I seen a less charming countenance. Ears askew, eyes of differing sizes, boxer’s nose, hairstyle frankly unspeakable. Stupid pointy cap. It is a small mercy that the photograph is a black and white one, for I dare not guess at the complexion of his skin. I suspect if you met Alfred Pigtosser in a dark alley at night you would run screaming.

Appearances can of course be deceptive, and it is no doubt remiss of me to judge him on superficialities. But then we open the book, and begin to read, and what do we find?

Chapter One

I am Alfred Pigtosser and this is my autobiography. My ears are askew, my eyes are of differing sizes, I have a boxer’s nose, and my hairstyle is frankly unspeakable. I like to sport a stupid pointy cap. My complexion is that of contaminated curd.

It’s not promising, is it? Yet the book has sold by the million. And this in spite of the fact that as far as I am aware nobody had ever heard of Alfred Pigtosser before. I’ve done my research, as always. That is why you come to Hooting Yard, because you know you can trust me to have done all that background reading and poring over reference materials and almanacs that you don’t have time for. In any case, you need not take my word for it. Here is how the autobiography continues:

Nobody has ever heard of me. That includes even my immediate family, for shortly after my birth I was abandoned in an orchard, where I was raised by squirrels. I lived in the orchard with the squirrels, wholly isolated from humankind, until my fortieth birthday. That day, I wended my way along a lane and across an extensive car parking area towards a hotel, where I registered under the name Flossie Partridge and took a room with a sea view. I do not think the receptionist believed I was really a Flossie, but I gazed at her in the way the squirrels taught me and she was duly hypnotised and reduced to an automaton.

In the hotel room, in between staring out of the window at the sea, I pounded the keys of a typewriter, bashing into shape this, my autobiography. I cannot claim it is packed with incident. One orchard- or squirrel-related anecdote drifts into another, samey samey. But when I have finished writing it, I know that all I need do is captivate people with the squirrel-gaze, and they will purchase as many copies as I command them to. I will have a bestseller on my hands, and untold millions in the bank, and then I will summon the squirrels from the orchard. How we then deal with the human population of the earth I have not yet decided, but I plan to write about it in a second volume of autobiography, tentatively entitled I, Alfred Pigtosser, And My Terrifying Army Of Squirrels.

On Flossie Partridge

Though his mighty brain confounded mere mortals, Sherlock Holmes was, of course, a dimwit in comparison with his brother Mycroft. Something similar may be said about Blossom Partridge and her sister Flossie.

Blossom is best-known as editrix of Miss Blossom Partridge’s Weekly Digest, quite possibly the finest weekly digest on this or any other planet. It remains, defiantly, a printed paper publication, though one feels sure that if Blossom ever countenanced the idea of going online, she would wipe the floor with the ghastly Arianna Huffington or with Tina Brown of the Daily Beast. Not the least of the charms of the Weekly Digest is that it is hand-written in Blossom’s immaculate copperplate and the copies duplicated on an ancient and creaking Gestetner machine. Blossom also refuses to acknowledge the horrors of decimalisation and the cover price has been held at 4d. By any measure she is a marvel of marvels among women.

Yet she would be first to bow to the even greater marvellousness of her sister. Flossie Partridge is a balloonist, aviatrix, explorer, inventor, secret agent, government spy, and the Lord knows what else besides. She could serve as a role model for any aspiring International Woman of Mystery, did she not remain almost entirely hidden from the public gaze. What little we know about her is thanks to hints dropped by Blossom in her magazine.

For example, Blossom has written movingly about the rare times the sisters spend together, when “we never walk like other people: we skip and gambol to show how girlish we are, as if we were Goosie and Piggy Antrobus”. She alludes to some of Flossie’s more hair-raising adventures in her regular “Glimpses of Flossie’s Hair-Raising Adventures” column, without ever going into the sort of detail that might compromise her sister’s obsessive, indeed maniacal, desire for secrecy. Thus, we might be afforded a “glimpse” of Flossie inventing a new serum, or in hand-to-hand combat with a giant anaconda, but we will not be told the purpose or recipe of the serum, nor the rationale or location of the death-struggle. Nor, incidentally, does Blossom divulge how one might engage in hand-to-hand combat with a beast that has no hands, though by omitting an explanation she guarantees a bulging postbag of readers’ letters.

Regular readers of the Weekly Digest will be aware that in virtually every issue, the “Dear Miss Partridge” letters page includes a lengthy, demented, and hysterical screed from a certain I. Alfred Pigtosser. Occasionally, Mr Pigtosser might address a topic raised in an earlier issue; more often, however, his letter will be a bitter and venomous harangue, barely coherent, shading at times into outright madness. Blossom has stated that it is her policy never to cut or otherwise edit her readers’ letters, and so there are times when a Pigtosser letter takes up six- or seven-eighths of the entire magazine. Readers complain, but Blossom remains unruffled.

It has not escaped the notice of her more astute readers that “I. Alfred Pigtosser” is an anagram of “Flossie Partridge”. Could it be, they ask, incredulously, that this poisonous invective is the work of the editrix’s marvellous sister? To which Blossom has responded by publishing grainy black-and-white photographs purporting to show Mr Pigtosser as an infant, on a tricycle, in a sailor’s suit, next to a large swan. She does not say how she came by these snaps, nor provide evidence of the (blurred) infant’s identity. On the other hand, Blossom is such a marvellous woman that she would surely not try to pull the wool over her readers’ eyes. It is a conundrum to be sure.

Speaking of wool, another of the regular features in the Weekly Digest is “Miss Blossom Partridge’s Woolly Blather”. Here one might find adventurous knitting projects, crochet extravaganzas, and disquisitions upon good wool and bad wool. Every now and then, the “Woolly Blather” and “Glimpses of Flossie’s Hair-Raising Adventures” columns are combined into one, as a surprising number of Flossie’s hair-raising adventures have involved wool in some form or other. One thinks of the incident when Flossie was engaged in hand-to-hand combat with a giant anaconda which, upon closer inspection, turned out to be an extensive draught-excluding sausage knitted entirely from the wool of a merino sheep. Blossom, with her typical editorial dash, appended a pattern so readers could knit their own. As if to provide fuel for the conspiracy theorists, the article prompted a letter from I. Alfred Pigtosser so lengthy, and mad, that it completely filled the next three issues of the magazine.

As far as is known, Flossie Partridge has never published a single word under her own name. Presumably she is too busy ballooning, flying aeroplanes, exploring, inventing, engaged on secret missions, spying for the government, and the Lord knows what else besides ever to find time to put pen to paper. Blossom has said, however, that once, when she and her sister were skipping and gambolling girlishly o’er the green to dance around a maypole, Flossie let slip that she kept a daily diary. It is said to run to thousands upon thousands of pages, scribbled in Flossie’s mad demented scrawl – so unlike her sister’s elegant copperplate! – and kept in an airtight and lead-lined storage facility in a subterranean cavern somewhere below the Swiss Alps. Who knows what secrets it contains? Marvellous secrets!

Blossom, or Flossie, or someone else entirely, as a child.