So, what was meant to happen at the latter end of last week was that Roland Clare and I would present our double act on literary nonsense to the sixth-formers of Truro School. (A riveting account of an earlier appearance at Bristol Grammar School can be found here.) A scheduling mixup hoo-hah meant, however, that instead of descending upon the not-so-tinies in tandem, Roland and I did our bits separately, on successive days. Improvising brilliantly. Mr Clare inserted into his presentation an old Hooting Yard On The Air recording, so my disembodied voice provided a foretaste of what had of necessity become the next day’s entertainment. The piece he chose was, appropriately, devoted to the subject of an unsuccessful educational initiative in Cornwall. It first appeared in Hooting Yard on 30 March 2006. Here it is again:

Dear Mr Key, writes Octavia Funnel, I am sure I read somewhere that Dobson’s companion and amanuensis, Marigold Chew, was a feral child, like the Wild Boy of Aveyron or Kaspar Hauser*. Is this true?

I think I can help Ms Funnel out here. She is clearly unfamiliar with Dobson’s rare and out of print pamphlet Ten Things Guaranteed To Drive Marigold Chew Crackers, an amusing bagatelle which he wrote for Marigold’s birthday one year. It is worth quoting at length:

Left, the Wild Boy of Aveyron. Right, Kaspar Hauser

There can be no doubt about number one on the list of things that drive Marigold Chew crackers. Countless are the times I have witnessed her seething with fury when she is mistaken for Mary Goldchew, the so-called Savage Infant of Splat.

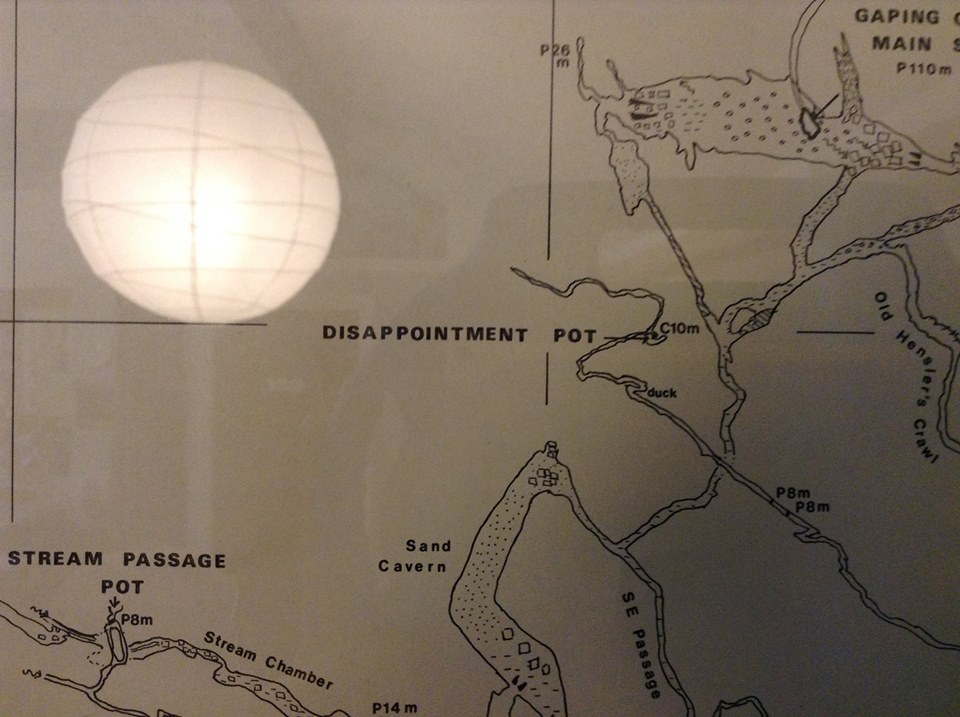

Splat is a tiny, stricken village in Cornwall, and it was here, on a muggy summer’s day in 19–, that a peasant pushing his barrow of countryside filth along a lane was astonished to encounter a small child roaring and spitting and growling and scrabbling in the muck. Its gender was indeterminate, but its savagery was unquestionable.

The peasant, sad to say, had the morals of the gutter and a heart as foul as a swamp, and he decided then and there to sell the child to a travelling circus or a zoo. Plucking the child from its ditch, he shoved her on to his barrow and trundled off towards a larger town where mountebanks were known to gather. But the child, bestial being that she was, sank her teeth into the peasant’s wrist and attacked him in a whirling frenzy of bloodlust. She was gnawing the hair off his head when a kindly doctor arrived on the scene. He patted her on the head and announced, “There, there, little one, be not afraid. I am a kindly doctor fascinated by Natural Philosophy, and I shall take you to my comfortable house and see if, over a period of months, or years, I can instil in you the civilised qualities that were your birthright but have been stolen from you by no doubt tragic circumstances. What is your name?”

The child howled.

“Ah,” said the kindly doctor, “You are inarticulate. That noise you made sounded to me like a combination of a wolf and a bear, with perhaps a touch of corncrake. I deduce that you have been raised since you were a baby by wolves and bears and corncrakes, and mayhap by bees and hornets too. Still, you must have a name, child, so I shall call you Mary.”

Doctor Goldchew took the child by the hand and led her to his house, which stood all alone in a field outside Splat. There, he dunked her in a disinfectant bath, dressed her in girly clothes, and embarked on a comprehensive pedagogical regime. Over the following weeks, he attempted to teach her metaphysics, arithmetic, rhetoric, logic, Latin, Greek, bread baking, botany, chemistry, religious instruction, conspiracy theory, merchant banking, astronomy, philology, and the rudiments of table tennis, or ping pong. During this time reporters from the Splat Courier & Bugle camped out on his doorstep, filing a series of woefully inaccurate stories about the girl they called the Savage Infant of Splat. Her fame spread throughout Europe, and Doctor Goldchew received visits from some of the most distinguished intellectuals of the day, including Kapisko, Blunkett, and Woobie. It was the latter who persuaded the kindly doctor to have the girl baptised by being fully submerged in the sea off the coast of Cornwall, during which baptism she nearly drowned.

She entered the booming ocean a savage infant, biting and squealing and howling, wrote the doctor, and she emerged as Mary Goldchew, a pious Christian child.

This is a selective account, of course. The doctor makes no mention of the drenched and spluttering tot who was fished out of the water by a passing trawler. Nor does he admit that the “pious Christian child” remained incorrigibly savage for the rest of her long, long life. In spite of the doctor’s lessons – to which he soon added physics, geology, alchemy, polevaulting, palaentology, entomology, knitting, forensic medicine, vexillology, Dianetics and pottery – the Savage Infant of Splat became a Savage Adolescent and in turn a Savage Adult. She celebrated her twenty-sixth birthday by creeping into Doctor Goldchew’s bedroom as he slept and smothering him with a pillow.

Thereafter she spent her days crashing around like a wild maniac as the once comfortable Splat house fell into ruin about her. When she died, craggy and ancient, decades later, she had learned nothing – nothing except to speak two words, the same two words that were the full extent of the Wild Boy of Aveyron’s vocabulary: God and milk.

*NOTA BENE : Specialists in the field would dub Kaspar Hauser a “confined” rather than “feral” child.