CLUBFOOTED TOT WINS HEROISM CUP. This was the headline on the front page of the Daily Brouhaha that first brought Tiny Enid to national attention. Until then, her heroic exploits were known only to a few. Her intervention in the case of the gormless nipper changed all that, at least for a while, until a fad or frippery came along to divert the fickle public. Yet some of us have not forgotten the heroic infant, and it is important that a new generation be reminded of her deeds.

The gormless nipper was roughly the same age as Tiny Enid, and of roughly the same diminutive stature, but otherwise the pair of them might have inhabited different planets. Where Tiny Enid was heroic, the nipper was gormless. Where Tiny Enid showed valour, gusto, and dash, the nipper was gormless, gormless, gormless.

The nipper was raised in an orphanage not unlike Pang Hill Orphanage. It was a monstrous black brick building crumbling upon a hillside. One winter’s day, the gormless nipper was leaning out of a window gazing gormlessly at the sky when he fell, landing in a gormless heap in the snow. Instead of trudging back to the huge iron door of the orphanage and rapping his tiny fist upon it until the kindly matron let him back in, the gormless nipper wandered off, away from his grim black brick home, ever further away, until he was quite lost. Thus began a series of accidents and misadventures which befell him due to his gormlessness. Stopping to rest at a level crossing, his cravat was singed by sparks from a passing locomotive. When he made to untie the cravat to look more closely at the singeing, he half-strangled himself and lost consciousness. Swooning, he fell forward so that the very top of his head almost touched the railway track, and when a second locomotive thundered past seconds later he received an inadvertent haircut, his locks torn out by the screeching metal train wheels. Had he had a mirror when he awoke from his swoon, the gormless nipper would have seen that he now had the appearance of a tonsured friar. He roamed onwards, crossing the tracks, and fell into a pond. Minuscule aquatic beings within the pond attached themselves to his skin and burrowed through to his innards, where they fed upon his tissue and squirted out pond-venom. They were microscopic beings (actual size), so the gormless nipper was unaware of their parasitic sucking and squirting, and the amounts of pond-venom were so infinitesimally small that even the most advanced scientific apparatus would be unable to detect them. Nevertheless he began to feel off colour and when, eventually, the venom reached his brain it had the effect of increasing, rather than alleviating, his gormlessness.

The nipper slept that night in a byre, surrounded by cows. Discovered at dawn by a florid-faced farmer, he was set to work pulling a plough through a field. The winter sun blazed on his tonsure and turned the snow to slush, and by the time he was done ploughing, the nipper’s socks were soaking wet. He took them off and hung them up to dry on what he thought was a washing line. Alas, it was an electricity cable running from the farmer’s generator to a new-fangled power spade, and the gormless nipper was jolted by a shock of sufficient voltage to make him queasy. So when, shortly afterwards, the farmer fed him a bowl of soup, he vomited it up all over the freshly laundered farmyard kitchen tablecloth, an heirloom embroidered with unbelievable delicacy by the farmer’s great great grandmother. Understandably furious, the farmer kicked the gormless nipper all the way down the lane into the village square at Scroonhoonpooge and abandoned him there.

Dazed and sore, still queasy, and with the pond-venom coursing through his vitals, the gormless nipper slumped against a plinth. The village beadle found him there, tonsured and sockless and with sick on his sleeves, and accused him of defiling the statue of frizzy-haired minstrel Leo Sayer atop the plinth, which was the pride of the village. Thrown into a dungeon, the nipper slept fitfully that night in the company of mice and beetles.

The next morning, the beadle handed the gormless nipper over to a brute to whom he would be apprenticed for the next six months. Day in, day out, the brute sent the nipper to the bottom of the sea in his bathyscaphe, from where he had to plunge into deep sea trenches and collect bioluminescent organisms. The goggles of his diving suit did not fit snugly, and the gormless nipper gradually began to lose his sight. When he was almost blind, the brute rowed him out to sea and left him marooned on a whelk-encrusted rock.

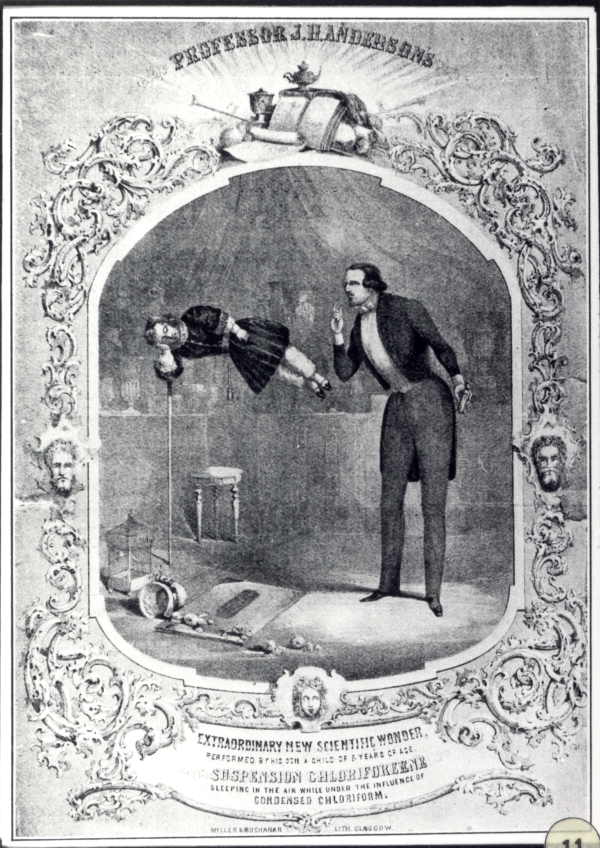

And there he may have perished were it not for Tiny Enid. One day, eager to do a heroic deed, she sailed aloft in her hot air balloon and spotted the gormless nipper weakly trying to prise the very last whelk from the rock. Rightly judging that he was far too puny and famished to hoist himself up any rope she might dangle down to him, Tiny Enid set her burners roaring and ascended high enough to snare a cumulet. Tying a quickly-scribbled message to the bird’s leg, she propelled it in the direction of the Air Sea Rescue Station at St Bibblybibdib, then descended again until she was in shouting distance of the gormless nipper.

“Fear not, nipper!†she cried, “I am Tiny Enid and I have alerted the Air Sea Rescue Station at St Bibblybibdib to your sorry plight by attaching a message to the leg of a cumulet. The bird is flying its little heart out even as we speak, and soon a lovely big lifeboat will scud across the waves to rescue you. Preserve your energy, and stop trying to prise that last whelk from the rock, for soon you will be sitting at my kitchen table wolfing down a slap-up hot dinner of non-seafood items!â€

And so it was that, nine months to the day since he had fallen from the orphanage window into the snow, the gormless nipper returned to his grim black brick home. He was driven there by Tiny Enid herself, in a hired charabanc, on the day after she was awarded a tin cup for heroism. The gormless nipper had managed not to be sick all over Tiny Enid’s tablecloth, and a few eye drops from her mysterious cabinet had restored his sight. The hair had grown back where it had been ripped out by the locomotive, and his heroic rescuer selflessly gave him a pair of her own socks to replace the ones still hanging neglected from the farmer’s electricity cable. Had Tiny Enid known that the nipper was riddled with microscopic aquatic parasites squirting pond-venom, no doubt she would have found a way of exterminating them. She was that kind of girl.