“We studied the whole theory of flight in very great detail, spending, I remember, more than a month in an examination of the wing of an albatross”

Rex Warner, The Aerodrome (1941)

“We studied the whole theory of flight in very great detail, spending, I remember, more than a month in an examination of the wing of an albatross”

Rex Warner, The Aerodrome (1941)

August has been exceedingly fecund here at Hooting Yard, with more postages in a single month than at any time since the site reared its gorgeous head almost seven years ago. However, I now wish to alert readers to the possibility that things may quieten down for a week or so, the reason being that a critical stage has been reached in the production of this year’s Lulu paperback. Yes!, fear not, fairly soon now your Christmas-present-purchasing-befuddlement will be washed away, like the blood of the lamb, with the publication of another fat (350 pages or thereabouts) anthology of mighty lopsided prose, direct from Mr Key’s pea-sized yet pulsating brain to the printed page!

The mind-numbing business of bashing the book together is at an advanced stage, formatting the text and proofreadnig and reformatting the text, etcetera etcetera ad nauseam.. This ought to be a simple matter, but as the ever-reliable Mr Fadhley, who directs the operation, points out, the programme used to create the book “was designed by nerds for nerds and is monstrously complex”. Think of that when, eventually, you clutch the treasured tome in your dainty little hands, as tiny as Scriabin’s, if that is an approximate description of your hands, though I realise it may not be. You may have huge hairy paws. It matters not.

So for the next few days at least I will be trying to tackle the remaining monstrous complexities. Should anything momentous bubble up in my cranium I shall try to post it here, but I thought it worth alerting you that things may quieten down just a tad.

Meanwhile, you might want to make a day trip to Beccles.

Another thing I found when fossicking in that cupboard was a scrap of paper on which was scribbled the following:

11 Petiver, Buddle & Doody. 48 Withering. 53 Rousseau’s wife. 56 Huttonian theory. 63/64 Buckland. 76 Robert Dick – biscuit. 77/78 McGillivray’s journey. 80 Philip Gosse diary entry. 82 Buckland concealed hammer on the Sabbath. 129 Discovery of plankton.

Deploying my Holmesian deductive skills, I worked out that these were notes I had made, long ago, when reading The Naturalist In Britain : A Social History by David Elliston Allen (1976). Seeking enlightenment, I located the volume on the teetering bookshelves, and turned to the relevant pages. In some cases, it is no longer clear to me what sparked my interest. Others, however, I was extremely pleased to be reminded of. Here are the relevant quotes:

“Rousseau’s extreme short-sight was such that at the best of times he saw the landscape as a blur, while his wife, in similar fashion, never knew which day of the week it was and never even learned to tell the time.”

“In many ways [Buckland] was undeniably a very curious person: an oddly truncated man… He sported childish jests and puns, devised peculiar contraptions, went in for the weirdest kinds of food… It was typical of him that he drove round in a special kind of carriage, strengthened in an ostentatious manner… he carried around a mysterious blue bag… he led his students on excursions into the field wearing quite incongruously formal clothes.”

“Robert Dick… ‘the Botanist of Thurso’ made it his regular practice to walk all day, for up to forty miles, with one ship’s biscuit as his only sustenance.”

“Philip Henry Gosse became so lost in his work that he registered the birth of his only child with the remarkable entry in his diary: ‘Received green swallow from Jamaica. E delivered of a son.'”

“The blanching or bleaching of the London fogs, by the improved methods of consuming smoke, must be a very fine thing for the dwellers in that overgrown city. We hear, however, of one old lady, a duchess, who thinks the fog now to be very vulgarly pale; and regrets the good old days of what she thought a much more picturesque gloom.”

Henry Hartshorne, 1931 : A Glance At The Twentieth Century (1881)

This week in my cupboard at The Dabbler, a bit of blatant puffery for the recording I made – with Germander Speedwell – of Christopher Smart’s bonkers epic Jubilate Agno. I am well aware that Hooting Yard readers have learned the habit of listening to it daily, setting aside the three hours necessary to do so. Now you will, I hope, be joined by the extended readership of The Dabbler.

This week in my cupboard at The Dabbler, a bit of blatant puffery for the recording I made – with Germander Speedwell – of Christopher Smart’s bonkers epic Jubilate Agno. I am well aware that Hooting Yard readers have learned the habit of listening to it daily, setting aside the three hours necessary to do so. Now you will, I hope, be joined by the extended readership of The Dabbler.

Fossicking in a cupboard the other day, I came upon a piece of writing I’d done late in the last century. It contains a splendid anecdote which I can now share with you:

In 1994 my sister, who lives in the United States, was on a visit back to England for a couple of weeks. One day we decided to pay a visit of homage to St Patrick’s Roman Catholic cemetery in Leytonstone, wherein lie buried the five Franciscan nuns whose drowning in the mouth of the Thames in December 1875 was the event which sparked Gerard Manley Hopkins to write The Wreck Of The Deutschland. It was an overcast day in late summer, and we trudged aimlessly around the stones, unclear as to what sort of tomb or edifice we were looking for. It is a fairly small cemetery, and after half an hour or so we were on the point of abandoning the search – I think it was beginning to rain – but as we were going back towards the gates we noticed that a light was on in the shabby one-storey building near the entrance. We went in, and were greeted by some sort of cemetery attendant. My sister began, rather haltingly, to explain that we were looking for the grave of some nuns who had been drowned and whom the poet Hopkins had written a… – The attendant held up a hand to stop my sister in mid-flow and, looking over his shoulder towards an ajar door behind him, called “Oi, Mario! Them nuns what drowned…” Enter Mario, another cemetery worker, who promptly led us to the plot, asked if we were German (as the nuns had been), and explained that “quite a few people come to look at them nuns”. My sister began a brief tutorial on Hopkins, but I think Mario had heard it all before – having delivered us to our tombstone, he rapidly headed back to whatever he had been doing before. Ever since, I have mentally subtitled Hopkins’ great poem “Them Nuns What Drowned”.

Photograph courtesy of findagrave

Instruct the tinies in your charge to read carefully the passage about Thomas Babington Macaulay’s great-grandfather. Allow sufficient time so that even the dimwits and the ones who drool will be able to complete the task. Standing imperiously at your lectern, your arms folded in the manner of the Reverend J C M Bellew, roar at the top of your voice the following set of questions designed to test the tinies’ comprehension. They should scrape their answers on their slates. Model answers are given below, just in case you yourself have failed to comprehend the passage because your brain is fuming with visions of sprites and monsters.

Q. What did the Laird take from the Minister?

A. The Laird took from the Minister his stipend.

Q. In the jaws of utter destitution, what was the Minister’s admirable cast of mind?

A. The Minister’s cast of mind was valiant.

Q. What was the outcome for the Minister’s health after some time had elapsed?

A. After some time had elapsed the Minister’s health was much impaired.

Q. To what feature of the weather was the Minister exposed in all seasons?

A. The Minister was exposed to the violence of the weather.

Q. We are told the Minister had no manse. What else had he not?

A. The Minister had not a glebe.

Q. Name two other things the Minister had not.

A. The Minister had not a fund for communion elements nor mortification for schools.

Q. For what else might the Minister have been able to use mortifications, had he had them?

A. Had he had mortifications the Minister could have used them for pious purposes.

Q. Where would the Minister have pursued his pious purposes?

A. The Minister would have pursued his pious purposes in Tiree and Coll both.

Q. Describe the air.

A. The air was unwholesome and fetid and murky and rank and corrupt and mephitic and damp and vile and foul.

ADDENDUM : I was going to suggest that in the next part of the lesson you get the tinies to deconstruct the passage, but having read the following, I suspect that would not be such a good idea:

“Asked to characterise the deconstructionists he has known, an exasperated professor who specialises in modern British literature delivered this tirade: ‘Arrogant, smug, snotty, meretricious, addicted to straw-man arguments, horrible writers who demand to be of the company of Jane Austen and Chaucer, appallingly ingrown and cliquish at the same time that they talk about expansiveness and new frontiers of discourse, unbelievably wooden and mechanical at the same time that they make their wooden and mechanical obeisances to jouissance and free-play, like all perpetual adolescents contemptuous of the past and convinced that by great good fortune the truth happened to be discovered just as they were hitting puberty, a daisy-chain of brown-nosers declaring their high-flown independence from the normal irksome constraints of community and continuity, who without the peculiar heads-I-win-tails-you-lose rationale of their arguments – if evidence and logic bear me out, fine, if not, we can always deconstruct them – would almost none of them have written an essay that could stand up in a decent senior seminar.'”

Quoted in David Lehamn, Signs Of The Times : Deconstruction And The Fall Of Paul De Man (1991). Sadly, Lehman does not reveal the identity of this prize ranter.

“In the beginning of the eighteenth century the great-grandfather of the famous Lord Macaulay, the author of the glowing and impassioned History of England, was minister of Tiree and Coll, when his stipend was taken from him at the instance of the Laird of Ardchattan. The slight inconvenience of having nothing to live upon did not seem to incline the old minister in the least degree to resign his charge and to seek a flock who could feed their shepherd. He stayed valiantly on, doing his duty faithfully by his humble people. But after some time had elapsed, ‘his health being much impaired, and there being no church or meeting-house, he was exposed to the violence of the weather at all seasons; and having no manse or glebe, and no fund for communion elements, and having no mortification for schools or other pious purposes in either of the islands, and the air being unwholesome,’—he was finally compelled to leave, much to his own regret and that of his poor little flock.”

Hattie Tyng Griswold, Home Life Of Great Authors (1886)

Here is another example of the Incoherent Twaddle Generation Method. This also dates from 1987, and is again from a decisively out of print Malice Aforethought Press pamphlet, Forty Visits To The Worm Farm, a story which also appears in Twitching And Shattered (1989) and in This Fish Is Loaded : The Book Of Surreal And Bizarre Humour, edited by Richard Glyn Jones (Xanadu, 1991).

The glands of the investing tissue secrete lime and deposit it always submerged. These arrest the spat at the moment of emission. They detach with a hook the piles covered with fascines and branches, if we can use the term, buried in the sands or mud, their polypiferous portion sallying into the water. The raches, roughened and furrowed down the middle with pointed spiculae, or tubercular ramifications prolonged in a straight canal, the columellar edge sometimes callous – this is the critical moment for the hapless bivalve! He seizes it with a three-pronged fork, aiding also the functions of the stomach, filled with villainous green matter, which is conical, swollen in the middle, diminished, and tapers off, producing new beings, covered with vibratile cilia, furnished with two fins, limited only by the length of the stem, but in a moment beginning to dissolve its corporation, a soft reticulated crust, or bark, full of little cavities. The hinder ones loosen their hold, with four or six rows of ambulacral pieces designated by the names compass, plumula, bristling envelope, levelled bayonets, smothered. Last come the terrible and multiplied engines of calcareous immovable thread-like cirrhi with transverse bands, many of which crumble. Sometimes they are dredged.

ADDENDUM : I note that Amazon has copies of This Fish Is Loaded for sale from $0.47. Alongside Mr Key, the book includes work by Woody Allen, Mervyn Peake, Vivian Stanshall, Alfred Jarry, Bob Dylan, and the great, great Leonora Carrington (and many more, not least Yoko Ono’s late husband).

Forgive me a spot of navel-gazing, but I wanted to make a few remarks that occurred to me while tippy-tapping out the lecture from long ago, almost a quarter of a century old.

As I indicated, it was a whim to post it. I remain fond of it, and it seemed worth resurrecting. I was determined to tap it out word for word, resisting the temptation to make any changes – which led me to wince, like the narrator, more than once. As with much, possibly all, of my pre-Wilderness Years scribbling, it contains a number of infelicities I would (hope to) avoid today.

What interested me were the three passages in quotations, the two statements by the judge and the letter from Flubb. The first two are exercises in methods I have not used in a long time (but which I enjoyed revisiting), the third is… I am not quite sure.

The judge’s summing-up in Curpin’s case is an example of my once much-practised version of Burroughs’ cut-up technique. No physical cutting was required. I used to buy a preposterous number of secondhand copies of National Geographic magazine, from the 1950s and early 1960s. (Around 1964 there was a change in their colour reproduction, and thereafter the photographs lacked the bright gaudy glory of the golden age.) The method, such as it was, involved casting my eyes over the text, more casually than skim-reading, until a phrase nabbed my attention, at which point I’d write it down and resume, looking for the next phrase, usually on a different page or a different copy of the magazine. Vast paragraphs of incoherent twaddle can be generated this way, my only contribution being a few tweaks here and there to make the prose flow grammatically.

The list of Flubb’s crimes is of course alphabetic. There was a time when I found this method indispensable, either for single paragraphs (as in the lecture) or to structure longer pieces, like The Immense Duckpond Pamphlet. I played around with variations, such as pairing letters in combinations or substituting alphabetic order with qwerty keyboard order. All very Oulipian.

As far as I can ascertain, what I think I was up to in the third bit, the letter from Flubb, was striving, tentatively, for my own style, my own voice. And it seems to me now that those two methods, the one pretty random, the other constraining, were decisive steps, that I wouldn’t write the way I do if I hadn’t relied on them for a while. (I also had a bash at surrealist “automatic” writing. The less said about that the better.)

End of solipsistic babbling. Normal service will be resumed.

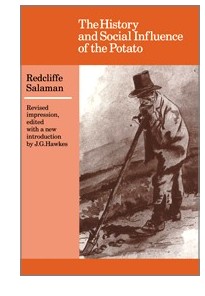

It is always worth keeping an eye on the Neglected Books Page, and today I am pleased to see attention paid to the potato.

It is always worth keeping an eye on the Neglected Books Page, and today I am pleased to see attention paid to the potato.

Here is a story from the last century, which I am posting because whimsy told me to. It first appeared in Tales Of Hoon (1987), and reappeared in Twitching And Shattered (1989), Malice Aforethought Press publications both of which are decisively out of print. It is called “A Lecture Delivered In The Big Tent At Hoon”. For younger readers in the UK, I should point out that back in 1987, none of us had heard of the ludicrous ex-MP Geoff Hoon.

Good evening. I find it difficult to express how pleased I am to see so many of you gathered here, squatting on rough-hewn wooden stools. And how gladdening it is that most of you have managed to bring along a fine selection of farm implements. They may well come in useful as illustrative material later on, if I manage to fit in the ‘audience participation’ segment of my lecture. But there may not be time – we have to be out of the tent at nine-thirty, as apparently it’s needed for a big display of pencil-crushing equipment. Still, we have until then, so let me waste no more time burbling preliminaries.

[Clears throat.] Seldom have criminality and wickedness been better personified than by Curpin and Flubb, the evil duo whose careers I wish to address this evening. Let me begin by outlining the panjandrums… I’m sorry, that doesn’t mean anything. [Shuffles papers. Winces.] Let me begin by reading from the judge’s summing-up at Curpin’s trial.

“Curpin has suffered tortures best left to the imagination, drawn his breath in shaking sobs, turned the animals loose, and has a power that men know not. He held the boards for seven terrible weeks. He burned fish. Approaching the startled cellists, he was seen grinding the pressure ridges, smashing great blocks of ice. He did not have time to rest. At the corral, under some sheaves of oats, and very snugly wrapped, he dropped his biscuit. Soon, he was dreaming of all sorts of extraordinary things. I saw him lift a man by the seat of government, rub down his horse, and feed him apples. He even went so far as to hire a top-rig buggy to take a little spin along the banks of foreign streams, procuring big booty and professing to be a detective. It was, indeed, a wild sabbath night. Curpin was furious with rage: one foot upon the iron rail, an enormous net of steel, and his pack-pony became visible. The time of winter dog travel was now approaching. The earth, gritty and metallic, could have bidden a gondola. Living rooms flanked the peristyle, and webs of incandescent tubular lamps shone ahead of the damp, grey relics. Curpin tracked down reports of locust swarms. He honked twice, slipped beneath the sea, went to work on a huge pile of food, and tore up lettuce, his pouch unfolding. His rattling became a sizzling. Even the nearby gravel-crushers were keenly aware of Curpin’s bone finger ring, embedded in mud. Gently, in order not to raise clouds of ooze, he blocked its incredible roped sledge and ox-hoof. Caught in a fish-hook curve, or pumped into the expensive bicycle crates, he touched up the ginger facade, decked his troublesome horse, and tampered no more with the tin roof. In fear and chaos, under a bridge or a water-tower, he became dusty blue with age. [Clears throat.] Like a sheet. Like rugs. Like concrete piles driven, and steel strung. Drying hazelnuts, this evil man on a screened porch with a syrup bottle provided by his hostess, punched, drilled, and reached a fine, convenient perch. He clapped a boatswain’s whistle to his lips, straddling the opposite slope, but his heart was seized by poisonous timber. In a modest salt-box structure of leaded casements, he brewed a big kettle of quahog berry candles, safely passed rocks made incongruous by a regatta in a dying wind, their examples of restoration one wooden thumb, with left foot thrust forward, and in summer often charmless. To converse with distant sheep, Curpin thundered past burning heather; he liked it better than mealy primrose. Blown by an icy blizzard, he had been trying out hemp and its by-products, twine, matting, and sacks. On the lawn, the seeming anachronism of Curpin’s indigenous cable plate politely softened the blue invalid jetty. He placed the wire cone with its point aimed at strewn torrents and a rack-and-pinion railway, harder, rarefied, tremendous. On the Seminole, formidable enough. For Curpin, it was the end.”

[Significant pause.] I think that speaks for itself as evidence of Curpin’s monstrous calumny. Of course, there was the usual small detachment of wishy-washy poltroons who said that the judge’s sentence was too harsh. But what on earth do you do with a man like that, except put him into a big iron pot and send it catapulting into the stratosphere? [Sneezes.] Excuse me. We come, then, to his wily accomplice Flubb. In the public mind, Flubb won greater sympathy than Curpin. Where Curpin was seen to be fairly riddled with infestations of abominable wickedness, Flubb was perhaps merely a cretinous apprentice. But is this true? Let us take a look at the catalogue of crimes which Flubb committed before that fateful meeting with Curpin at the Baize Works. Once again, my source is the trial transcript.

“Be it known that the said Flubb has confessed to the following stupendously wicked deeds: abnormal behaviour in the botanical gardens; bamboozlement of the grossest kind; clutching a bag of wheat-husks in his sweaty fist; dental irregularities; employment of minors for the purpose of illicit gurgling; forging railway timetables; glowing in the dark; hooting at elderly farmyard animals; implacable dribbling; jumping off wooden crates; knitting a quite disgusting balaclava; leaning against a zoo; malfeasance in a charnel-house; not paying corkage; oddly-laced boots; pouring forth incandescent light in a public place; quietude when surfing; ribcage abuse; skulking about very suspiciously; taradiddle and ergot; uprooting foliage with his teeth; virulent horseplay; wiggling unnecessarily in a lab; x-raying entire continents without permission; yodelling aboard a tractor; zest for crumpled, bristly things…”

The list goes on, but time is tight. We must continue apace. [Wheezes.] It is obvious, then, that Flubb was as much a villain and a fiend as his partner. If not more so. Indeed, a careful examination of his brain-tissue – [Suddenly hoists aloft plastic bag full of goo.] – would show us… er… I do apologise. [Replaces bag in pocket.] Sorry about that. [Wipes hands on sleeves.] Sorry. A careful examination of the diaries kept by the two men during their reign of terror would show us that, if anything, Flubb was the real mastermind, Curpin merely doing his bidding in exchange for a boiled sweet, a pencil-case, or some other little token of appreciation. Is it possible, then, that the public image, the public perception, of the two fiends is awry? That a monstrous injustice has occurred? You will recall that Flubb was not sentenced to be put into a big iron pot etcetera etcetera. No, the judge decided that he was a poor misled urchin who deserved a second chance. Thus it was that he was banished to a pompous land, thousands of miles away, to darn flags and buff up ceremonial shields with a frayed rag. So far as any of us know, he remains there, doubtless continuing to plot inordinately foul crimes. [Pause.] Or does he? I am now able to confirm what some of us have long suspected – that Flubb has decamped from his banishment and is, even as I speak, here among us in Hoon. [Flourishes grubby piece of paper.] I hold in my hand a letter from this hound of hell. Allow me to read it to you.

“Dear Waldemar,” it begins, “I never cease to be astonished by the hedgerows of Hoon. Where else can one see topiary so enigmatic, so imperious? Ah, how I missed them in that pompous land of my exile, where the hedges were dappled with pinks, foxgloves, and many other flowers I knew not. Beauteous as they were, I yearned to see the hedgerows of my home town in all their magnificence. I have at last begun work on my magnum opus, Topiary & Miscegenation, sorting out ten years’ worth of scribbled jottings, notes, and references. It is tough work, but rewarding for all that. I eat only little, drink even less, and can hardly bear to sleep. My mind is on fire with incalculably evil schemes of iniquity and mayhem, most of which I hope to put into practice within the next fortnight, God willing. As I write, the evening light shimmers around me, and tiny winged things flutter about my head. I feel that I am enveloped by a transcendent stillness, as if someone had bashed in my skull with an adze. Light, incandescence, grace; I may yet find grace.”

[Pause.] It’s signed “Passionately yours, Flubb”. An intriguing document. Naturally, I submitted it to a veritable barrage of forensic tests to confirm its authenticity. It appears to be genuine, although I have yet to subject it to the final test, perhaps the most trustworthy one. I speak of course of the Bails-Frampton Experiment, only recently developed. It is visually most attractive, so I thought it might be a rather stimulating climax to my lecture. Please don your goggles; you’ll find them nestling under your stools. [Constructs immense panoply of esoteric bakelite equipment on dais. Dons goggles. Equipment whirrs, hums, shoots sparks, etc. Carries out Bails-Frampton Experiment on grubby sheet of paper. Removes goggles.] Apparently, this is a genuine document. In other words, Flubb has eluded his keepers and returned to Hoon. A criminal genius lurks once again in our midst. You may remove your goggles. [Pause.] That appears to be all we have time for, I’m afraid. [Peers towards back of tent.] I am being gesticulated at by the janitor. Thank you so much. Are there any questions, very quickly? [Member of audience poses question.] Thank you. Indeed. [Pats jacket pocket melodramatically.] What is this bag of goo in my pocket which I suggested was the vile jelly of Flubb’s brain? Ha ha. I am still being gesticulated at by the janitor. A most pertinent question, if I may say so. The janitor is still gesticulating. I’m afraid we shall have to make way for those damned pencil-crushing people. Thank you again, very much. And goodnight.

“Street addressing is one of the most basic strategies employed by governmental authorities to tax, police, manage, and monitor the spatial whereabouts of individuals within a population. Despite the central importance of the street address as a political technology that sometimes met with resistance, few scholars have examined the historical practice of street addressing with respect to its broader social and political implications… We are particularly interested in showcasing recent work that links the history of urban house numbering to broader debates concerning the interrelations of space, knowledge, and power that have animated contemporary discussions in the social sciences and humanities.”

Call for papers for a special section in the journal Urban History on the history of urban house numbering, cited in Pseuds’ Corner, Private Eye, No. 1269, 20 August – 2 September 2010.

In his days as an armchair revolutionary, Blodgett became peculiarly exercised about urban house numbering. He lived at the time at 6 Rolf Harris Mew. Most Mews are plural, but this one wasn’t. There were nine bijou little dwellings in the Mew, and with what Blodgett identified as a typically hegemonic capitalist patriarchal linear system of oppression they were numbered, consecutively, from one to nine.

Blodgett had to subject this system to a rigorous poststructuralist interrogation before he was in a position to subvert it, and this he did, strolling up and down the Mew making notes, accompanied by impossibly complicated diagrams, in his jotting pad. Across the way, crippled mendicants, brought to such a state of destitution that they were lower even than the lowest of the lumpenproletariat, wallowed in their own filth and wailed for crumbs. Blodgett occasionally went over to consult with these wretches, garnering their views on his important research.

His first step in defiance of an unconscionable tyranny was to upend his door number so that it looked like a 9 rather than a 6. For this blow against the system he was shouted at by the postie and beaten insensible with a club by the occupant of number 9. Blodgett had, of course, expected violence as the response to his supremely transgressive act. But, he asked himself as he lay bandaged in a clinic, was it transgressive enough?

When he was well enough to return home, he stole out one night and, using a screwdriver, removed the door number from each house in the Mew. He made a pyre of them and set them ablaze, using an oil-soaked rag liberated from one of the mendicants. By the light of the fire, he took a paint pot and daubed upon each door a slogan of resistance. For this, he was again shouted at by the postie, and again beaten insensible by the occupant of number 9, a person labouring under false consciousness who was joined, on this occasion, by three or four of the neighbours.

This time, upon his discharge from the clinic, Blodgett discovered that all trace of his daubings had been erased, and brand new metal numbers affixed to the doors, except his own, which now had nailed to it, in a clear plastic bag as protection from the incessant rainfall, a notice from the civic authorities. Blodgett sat on the stoep to read it. In essence, it told him that he was a fathead and an idiot.

Poor Blodgett! For a while it looked as if he might be homeless, and have to join the wretched untermenschen across the way. But then he had one of his magnificent Blodgettian brainwaves. He scampered off to the civic authorities’ oppressive brutalist headquarters and explained to an official that he was an artist. This declaration did the trick. He was welcomed back to Rolf Harris Mew as a returning prodigal, even by the bourgeois scum at number 9, and resumed his activities, talking Twaddle to Power.

R.I.P. Bruno S. “…a man of phenomenal abilities and phenomenal depth and suffering. It translates on the screen like nothing I have ever done translates on to a screen.” – Werner Herzog

Time now for the ever-popular Hooting Yard Toad Quiz, where you can sharpen your wits by testing your knowledge of toads.

Here is a photograph of a toad. Study it very carefully for five or ten minutes. It is, of course, a Kihansi spray toad, a tiny little dwarf amphibian just three-quarters of an inch long, native to Tanzania. (I am referring to the larger of the two toads in the picture. You can ignore for the time being the even tinier baby Kihansi spray toad clinging to the back of the adult.) When you think you have prolonged your careful study for a sufficient period of time, answer the question below the picture.

Is this Kihansi spray toad (a) cheerful, (b) mordant, (c) choleric, or (d) hysterical?

You will find the correct answer here.