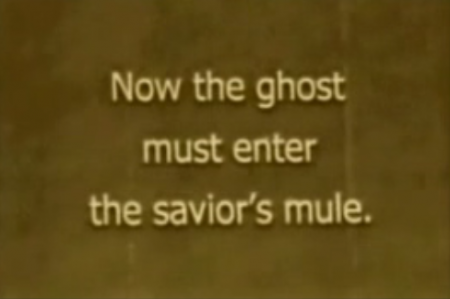

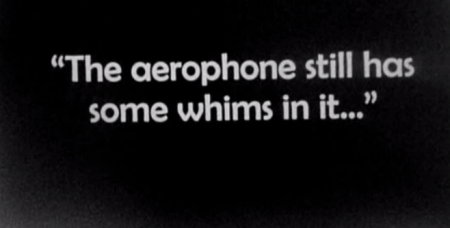

Brand Upon The Brain! (2006)

Brand Upon The Brain! (2006)

An old Latvian folk song, translated from memory. To be sung when gathered round a blazing hearth on a bitter winter’s night.

There is a shepherd in the hills

There is a [something] green

But black is the crow in the [something] tree

And forked lightning blasts the sky

The shepherd’s lass has golden hair

She [something something] milk

But the crow has flown away, my love

And the ducks have left the lake

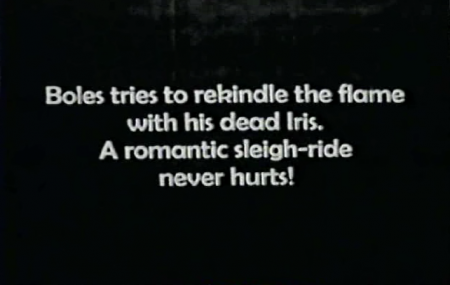

Cowards Bend The Knee (2003)

There is a story I remember from my childhood called “The Brass-Necked Goose”. Or rather, I remember the title, but not much of the story itself. As far as I recall it involved a goose that was ordinary in all particulars except that its neck was made of brass. One accepts such improbabilities as a child, as indeed one continues to accept them, when grown, if the spinner of improbable tales is a skilled one.

If, for instance, a Latin American magical realist with a clutch of literary awards under his or her belt introduces into a fat novel a goose with a neck of brass, we might have a moment where we say “pish!” or “pshaw!”, we might even chuck the book across the room into the fireplace, but more likely, given the laurels with which the writer is garlanded, we will accept the goose and read on, dazzled by the author’s inventiveness.

On the other hand, if we are reading a book by some lesser-known writer, and one, say, whose infelicities of style and bone-headed stupidity have already tempted us to chuck the book into the fireplace, and then, as we are growing increasingly exasperated, a goose with a brass neck is introduced for no compelling reason on page 114, then “pish!” or “pshaw!” are going to be the mildest expletives with which we will erupt, accompanied no doubt by curses unsuitable for delicate ears. We will also be likely not only to give in to the temptation and to chuck the book into the fireplace after all, but to ensure that a roaring fire is blazing therein, the better to obliterate this farrago of printed nonsense from our memories.

But as children, we do not care two pins for the literary reputation of the writer, and we are immune to infelicities of style and even to bone-headed stupidity. As children, we are caught up in the story, however improbable, however ill-written. For one thing, we are probably not reading but being read to, by Mama, as we lie tucked snug in bed, our bellies warm with milk, our eyes fixed on the paper stars glued to our bedroom ceiling. When we are told that Ipsy Dipsy, limping along the lane, meets a goose with a brass neck, we simply accept that this is the kind of thing that happens to Ipsy Dipsy, and might even happen to us, if ever we find ourselves walking along a country lane, unlikely as that may be given that we live in a hideous urban sprawl with barely a sprig of greenery to be seen.

I said I could not recall the story, but see! see!, I have remembered Ipsy Dipsy and the lane. Little details reappear in my mind’s eye. I remember Ipsy Dipsy’s pointy red hat, and the callipers on his legs, for Ipsy Dipsy was a cripple, at least at the beginning of the story. I remember the lane, it was a lane like the avenue at Middelharnis painted by Hobbema. Was Ipsy Dipsy Dutch, or Flemish? Was he still wearing the callipers at the story’s end, or had he been able to cast them aside, to throw them happily into a ditch, on account of some magical cure effected by the goose? Did the goose’s magic powers inhere in his brass neck?

As quickly as the memories come shimmering, like the paper stars on the ceiling long ago, so, equally quickly, they fade, like the stars will fade in the heavens. The night sky will be black, and vast, and pitiless. And I will totter about, fumbling in the darkness, aged and exhausted, knowing that there will be no brass-necked goose to save me from extinction.

Originally posted in 2014.

Brand Upon The Brain! (2006)

Cowards Bend The Knee (2003)

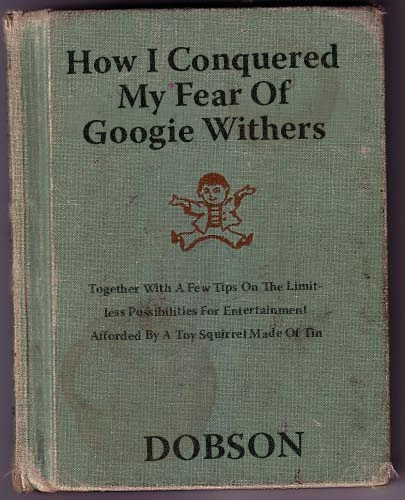

An important out of print Dobson pamphlet, with a cover design by Marigold Chew Daniel Tomasch.

Yesterday’s episode of Hooting Yard On The Air was the final show for the Year of Our Lord MMXVII. As a special treat for listeners’ ears, it included a rather marvellous rendition of The Cuthbert Spraingue Song, for which Mr Key was joined by the dulcet tones of Pansy Cradledew. Thereafter, there was a lot of babble about an ogre, and Dobson, both on an atoll and in a pickle. Plus an end note on Italian fascist Benito Mussolini.

Meanwhile, don’t forget that ancient episodes of the show are being regularly added to an archive on YouTube.

Sombra Dolorosa (2004)

kr

I had a cuppa with Tilly Losch

Just tea, the caff was out of nosh

It cost an awful lot of dosh

Then we went to a pit to moshOh Tilly! Such a smashing gal

Nowadays she’s my penpal

We swap letters ‘cross oceans wide

Oh Tilly! Tilly will abideAbide with me

Abide with Ned

Young Edward James

Shared Tilly’s bedSoon enough the pair did part

Ned collected surrealist art

Some influenced by old H. Bosch

But he never forgot Tilly – Tilly Losch!

Brand Upon The Brain! (2006)

See Vercingetorix. Vercingetorix is puny. Hark! Hear Puny Vercingetorix clank. Wherefore does he clank? It is the clanking of his armour as he marches. Puny Vercingetorix is marching in his armour o’er the hills and far away.

So puny is Puny Vercingetorix that he has fallen behind the other marchers. Yes, there are other marchers. He does not march alone. Puny Vercingetorix is merely one tiny puny cog in a martial host. It is an army, clanking o’er the hills and far away. Puny Vercingetorix is bringing up the rear, having fallen behind, so far behind that even if his vision were piercing he could barely see the host ahead. But he is short-sighted as well as puny. He is short-sighted and has no spectacles, for nobody in the army is allowed spectacles. It is like the court of King George III.

What usually happens when a straggler falls far behind the marching host is that they are waylaid and carried off by marauding bears. There have been countless newspaper reports of such occurrences, most distressing, most distressing. But Puny Vercingetorix, though he is puny and myopic and neurasthenic and prone to terrible fits and something of a halfwit, is nevertheless possessed of a singular quality which, in his current circumstances, is as valuable as a chest crammed with precious stones. Puny Vercingetorix speaks the language of bears, at least the language of the bears that roam these hills far away.

He was taught to speak with bears when tiny, attached to a travelling circus.

Now, if as a straggling marcher cut off from the host he is waylaid by bears, Puny Vercingetorix will tilt his head to the appropriate angle, and raise one eyebrow, and make significant passing movements with his hands, and from his throat will erupt the most extraordinary noise. And the bears, rather than carrying him off to their lair, there to do him unimaginable harm, will each of them flop to the ground and flail about, beatific smiles on their faces. In the parlance of Doddy, he will have tickled their funny bones.

Up ahead, the host is clashing with a rival host, an army terrible with banners. Puny Vercingetorix is well out of it. He sits on a clump, and takes from his pouch his curds and whey, and snacks upon them, waiting for bears. It is the first Thursday of the fifteenth century.

And that piece first appeared in the first month of the Year of Our Lord two thousand and fourteen.

Archangel (1990)