One misty morning, Tiny Enid was reading the latest issue of her favourite comic, The Ipsy Pipsy Woo, when, in a speech bubble hovering over the head of a character called the Very Reverend Prebendary Septimus Widdecombe, she came upon the words “the dustbin of historyâ€. Specifically, she learned that every now and then there were people or institutions or events that were consigned to this dustbin. Tiny Enid thought this was a very sad state of affairs, but she was not a mawkish weepy kind of girl, so she did not sob into a napkin.

A helpful footnote in the comic explained that the existence of the dustbin was first revealed by a beardy bespectacled Russian revolutionary who ended up with an ice-pick in his head. Such a gruesome fate did not bother Tiny Enid one iota, for she could herself be ruthless as occasion demanded. She was alarmed, however, to read that the dustbin might not be a dustbin but a mistranslation of ash heap. If that which was consigned to it was incinerated, she reasoned that it would be beyond salvage. For already, you see, being the impetuous infant adventuress she was, Tiny Enid had decided to find the location of the dustbin of history and to rescue its contents. This seemed exactly the kind of mission for a plucky youngster who had been twiddling her thumbs in idleness for an entire fortnight, without a single daring escapade to speak of.

Casting The Ipsy Pipsy Woo aside, Tiny Enid took down an atlas from the bookcase. It was such a huge atlas that it probably weighed more than she did, but she managed to slam it down on to her lectern. The lectern was a full size one, donated to Tiny Enid by a grateful vicar whom she had rescued from the jaws of death in the jungle where he had a bit part in a Werner Herzog film, and she had to saw off part of the base to make it just the right height for her diminutive stature. Deciding not to worry overmuch about whether the dustbin was actually an ash heap, she skimmed hurriedly through the atlas looking for places where a pretty large dustbin or ash heap might be concealed. Although neither the speech bubble nor the footnote in her comic suggested that the dustbin of history was hidden away somewhere, Tiny Enid intuitively felt that must be the case, and she often relied on her intuition, which, as she explained to those who asked her, was not feminine intuition so much as heroic club-footed infant intuition, a different kind of intuition entirely, and far more accurate. It was, after all, her intuition which led the brave tot to track down the vicar on location in the jungle with Werner Herzog rather than, say, elsewhere with a director such as Jean Luc Godard or Guy Ritchie.

Pinpointing a large, flat, windy and uninhabited area on one of the continents, Tiny Enid packed her pippy bag with supplies and vroomed off in her jalopy towards the aerodrome, terrifying geese and ducks and roadside mendicants as she drove pell-mell along the winding country lanes. Hopping into her bi-plane, she roared away, out of the mist and up into the immense blue firmament, begoggled and begloved and chewing on a radish. She thought it would be a good idea to contact her mysterious unseen mentor to let him know what she was up to. We first encountered this mentor in an earlier story where he was introduced for intricate plotting purposes, without any clear idea of his identity. No need to worry about that now, however, for when Tiny Enid reached for the pneumatic speaking funnel she realised it was clogged with dust and pebbles. Even if she did manage to get a signal, all her mysterious mentor would hear from her would be mangled mufflement. She threw the funnel aside and revved her engines with renewed derring-do.

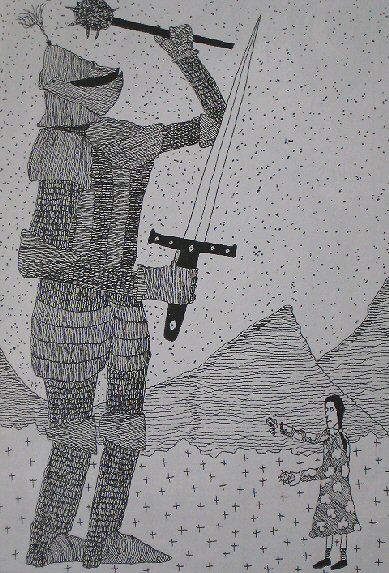

There was much turbulence during the flight, and much turbulence too inside Tiny Enid’s head. We think of her as a self-possessed and unflappable heroine, and she was, but often that resolute exterior masked inner turmoil. Like any of us, Tiny Enid was subject to entrancements and ecstasies, to sloshes of despair and to cranial hullabaloo. Weirdly, rather than planning what she would do if the dustbin of history turned out, after all, to be an ash heap, and an ash heap in a flat windy area where the ashes would be blown and scattered, she was instead mulling over something else she had read in that week’s Ipsy Pipsy Woo. In his weekly column, Father Ninian Tweakling had set a moral conundrum. Faced with the choice, which would you save from a burning tower – a half-starved yet impossibly cute puppy, or the horned and cloven-hooved incarnation of the Devil himself? This was precisely the kind of daring rescue Tiny Enid could imagine herself making one day, but she had to discount her immediate response, which was that she would cleverly extinguish the fire, carry the puppy directly to a dog hospice, and return to save the Devil, but bind him in chains and make him promise to mend his ways. Father Tweakling made plain that there was a choice to be made, between puppy and Beelzebub, and a great moral lesson to be derived from the making of it. Tiny Enid had been turning it over in her mind for a couple of days now, and it continued to busy her brain as she soared through the sky towards where she hoped she would find the dustbin of history.

She had still not come up with an answer when she brought the bi-plane down on to a landing strip attached to an apricot pericarp testing station. From here, she would have to hike across the plains, but first she stopped in at the station and asked the fruit scientist based there to give her a cup of tea.

“Tell me,†she asked in her shrill, fearless way, “Am I right in thinking that about fifty miles west of here across the plains I will find an enormous dustbin?â€

The fruit scientist paused in his tea making, fixed the plucky tot with a watery gaze, and said, “Ah now, miss, some say as there is and some say as there ain’t. And me, I wouldn’t rightly know neither way. Milk?â€

“You speak more like a bumpkin than a fruit scientist, sir!†shouted Tiny Enid, “And yes please, milk in my tea, thank you.â€

Even though she was irritated by the fruit scientist’s semiliterate drivel, Tiny Enid never forgot her manners.

“Why might you be looking for a big dustbin all the ways out here then, little one?†asked the fruit scientist.

“Because, O man of apricot pericarps, I am resolute and intrepid,†replied our heroine.

And soon enough, as good as her word, Tiny Enid was on her way across the plains. As she thumped her way westwards, she wondered if the fruit scientist had been putting on an act in a misguided attempt to warn her off. Could the dustbin of history be a dangerous dustbin? If it was, Tiny Enid would be not cowed, she would snub her nose at it and carry on regardless, for she was frightened of nothing. She stopped at a place that was a bit less flat and windy than the rest of the plains and sat and smoked a cheroot, taking from her pippy bag the gazetteer she had packed earlier. Consulting the index, she saw that there were entries for neither Ash heap nor Dustbin but under History she found an illuminating survey of everything that had happened upon the plains for the last thousand years, from the battle of the boppityheads to the hunting to near extinction of the lopwit to droughts and floods and windiness to the establishment of the apricot pericarp testing station. It was all very interesting, and Tiny Enid lodged it in her memory banks. One day, she knew, she would no longer be tiny, and adventure would lose its allure, and she pictured herself grown and a bit dotty, sitting in a cottage writing her memoirs, and she wanted to forget nothing, for she was determined that she herself would never be dropped into the dustbin of history.

And then she sat up with a start. It suddenly occurred to her that, when she found the dustbin, and peered down over its edge, she might lose her footing and topple into it! Perhaps it had a greasy rim, or lethal uneven patches where it had been gnawed by wild animals. She rummaged in her pippy bag and blasted the heavens that she had not brought a goodly length of mountaineer’s rope and clambering hooks. Well, she had faced peril before and would face peril again. Stubbing out her cheroot and crushing it under her corrective boot, she pressed on into the west.

The sun was sinking when Tiny Enid arrived at a compound surrounded by a security fence. She smiled to herself at the thought that, though she may have neglected to bring mountaineer’s rope and clambering hooks, she never went anywhere without her razor sharp security fence slicing shears. Dipping into her pippy bag to get them, she read a sign affixed to the fence. Large Flat Windy Uninhabited Plains Municipal Hygienic Waste Disposal Chute Compound, it said. Tiny Enid stamped her club foot and let out a shrill cry. The dustbin of history was neither a dustbin nor an ash heap but a chute! This put an entirely new complexion on her adventure. To salvage those things that had been deemed historical irrelevancies, she would have to find where the chute terminated, somewhere subterranean, and she had not brought a spade. One option, of course, was to fling herself recklessly down the chute, but that would be like toppling over the edge of the dustbin. She put the shears back in her pippy bag and sat down to think. She wondered if the lesson to be learned from the answer to Father Tweakling’s moral conundrum could help her now. A burning tower, a starving puppy, the Devil incarnate, and now add a hygienic waste disposal chute…

All of a sudden, Tiny Enid knew exactly what to do. She raced back to the apricot pericarp testing station, felled the fruit scientist with a few well-aimed kicks to the head and the stomach, clamped a bleeping tracker device around his ankle, shoved him into a wheelbarrow, pushed him west across the plains, disabled the municipal compound alarm system, sliced a hole in the security fence, and dumped the fruit scientist down the chute. Popping a radish into her mouth, she snapped open the tracker device palmpod, and watched as the fruit scientist’s avatar, a cartoon head bearing a striking resemblance to Ringo Starr, tumbled, beeping, deeper and deeper down below the windy plains, tumbling and beeping, until at last it came to rest at what the coordinates told Tiny Enid was the earth’s core. So this was the dustbin of history.

Tiny Enid had attended enough geology lectures to know that the centre of the earth is a ball of ferociously hot boiling burning magnetic rock, and that pretty much anything tumbling out of a chute on to it would not survive for a moment. She knitted her brows, fretful that her daredevil mission looked set to end in failure, a word, of course, the diminutive adventuress neither acknowledged nor understood. Turning on her heel, she clumped back across the plains to the landing strip, and steered her way across the skies until she was home, and she sat at her table scoffing down a bowl of milk slops, resting her club foot on a dimity cushion. By the time she had drained her bowl, she had a plan. Part of it would have to wait until the next issue of The Ipsy Pipsy Woo came out, wherein she was sure a moral conundrum from Father Ninian Tweakling would lead her on the correct path, once she had solved it. But the other part of her plan could be set in motion immediately. Lurching over to the desk upon which her metal tapping machine sat polished and gleaming, she transmitted a message to her mysterious unseen mentor.

I must journey, Jules Verne-like, to the centre of the earth, she tapped, and clearly such an expedition will cost a bob or two. Please start a fundraising appeal immediately. Yours sincerely, Tiny Enid.

And thus did the venturesome mite’s next hectic and compelling adventure begin.