Monthly Archives: December 2008

Fuge

Michael Gilleland at Laudator Temporis Acti has a marvellous post on words ending in –fuge. He notes Thomas Hardy’s coinage of dolorifuge in Tess Of The D’Urbervilles –

“The children … had made use of this idea as a species of dolorifuge after the death of the horse.â€

– and cites a contemporary reviewer of Hardy complaining about his “outlandish words†–

“Think how absolutely out of colour in Arcadia are such words as ‘dolorifuge’, ‘photosphere’, ‘heliolatries’, ‘arborescence’, ‘concatenation’, ‘noctambulist’ – where, indeed, are such in colour? – and Mr. Hardy further uses that horrid verb ‘ecstatisize’.â€

There are many more –fuge words to chew over, and I may well make use of some of them in the coming year.

Spillage On Cambric

Having spilled soup on a piece of cambric, the verger tried to amend his sloppiness by dabbing at the cambric with a damp sponge. Alas, so much chemical colourant had been added to the soup, which was of a tomato flavour, and so hastily and violently did the verger do his dabbing, that a bright orange stain was impressed into the cambric. The cambric, by the way, was blue with golden stars, like the vault of heaven. Fearing that he had ineradicably besmirched a representation of the ethereal realm, the verger hid the cambric and the sponge in a cupboard and poured the remainder of his tomato soup down the drain. He cleansed his bowl and spoon with more care than he had dabbed at the cambric, and placed them exactly where he had found them among the crockery and cutlery, having first dried them with a tea towel depicting the martyrdom of Saint Anselm. This was an historically inaccurate tea towel, as Saint Anselm died a natural death rather than being martyred for his faith. It was not the only erroneous tea towel in the kitchen.

The verger hoped that hiding the evidence of his sloppiness in the cupboard would prevent it from coming to light, but he reckoned without the involvement of Detective Captain Cargpan. The detective was called in by the bishop on an unrelated matter, something to do with the local sniper, who had been taking potshots at the cathedral hens. Cargpan was noted for his energetic approach to police work, and on this occasion he strained so many sinews that by midmorning he was exhausted and dehydrated. Characteristically, he did not whimper to the bishop begging for refreshments, but instead blundered about until he found the kitchen, where he intended to gulp down water straight from the tap. Having done enough gulping to make himself feel human again, Cargpan could not resist opening all the drawers and cupboards in the kitchen and examining the contents with his magnifying glass.. Such was his method. Although it was unlikely that either the sniper or the hens had ever been in the kitchen, the detective assumed nothing. Thus it was that he discovered the hidden cambric and sponge. He was extremely suspicious of the bright orange stain.

Under questioning, the verger admitted his part, but insisted that the sponge and the cambric had no connection to the sniper and the hens. Detective Captain Cargpan roughed him up a bit, breaking one of his arms and dislocating his jaw. This, too, was his method. The verger continued to protest his innocence throughout his subsequent trial and the long years on the prison hulk moored off an unspeakable stretch of coastline. Long after his death, campaigners sought for him a posthumous pardon. But we now know that Cargpan was right all along, and that the verger and the sniper were one and the same. Interviewed for a television documentary during his long and happy retirement, Cargpan explained that, for him, it was an open and shut case.

“A man who can smear tomato soup upon a picture of the vault of heaven, and who makes use of historically erroneous tea towels, is precisely the sort of man who would shoot at innocent clucking hens with a Mannlicher-Carcano rifle,†he said. Today we are at last able to acknowledge the wisdom of those words.

Old Farmer Frack’s Haircut

Old Farmer Frack usually cut his own hair, hacking at it with a pair of shears, but one day he left his cows in the care of a hired urchin and strode to the nearest village to seek out a barber. There was no barber in the village, so Old Farmer Frack carried on along the lane until he came to another village. Here he found, not a barber, but a hairdresser. Unlike many hairdressing establishments, which are fond of punning names such as Hair Apparent or A Cut Above and so on and so forth, this one was called simply Rudimentary Hairdressing For Peasants, which suited Old Farmer Frack down to the ground.

He crashed in through the door, threw himself into a chair, and as the mildly startled hairdresser tucked a sheet around him, he bellowed that he wanted a “chop sueyâ€.

The hairdresser had no idea what this mad old farmer was talking about and tried to explain that the only haircut available was a rudimentary one suitable for a peasant.

Old Farmer Frack shouted that as far as he was concerned, a “chop suey†was a basic haircut, and commanded the hairdresser to get on with it.

Hairdressers are not cows, however, and are much less tractable. This particular hairdresser took much pride in her work, and was not about to embark upon a haircut the lineaments of which she was ignorant. So she asked Old Farmer Frack to describe the “chop sueyâ€. As farmers go, Old Farmer Frack was a highly intelligent man with an acute visual sense and a more than serviceable vocabulary, but he was also mad, so in reply to the hairdresser he blathered a scarcely intelligible farrago of nonsense. So persuasive was his tone of voice, however, that the hairdresser was spellbound and convinced that she actually had some understanding of what he was saying. No sooner had he shut his trap than she hacked at his hair with a pair of pruning shears, for all the world as if she had been practising the “chop suey†for years.

Old Farmer Frack was well pleased with the result, gave the hairdresser a generous tip in addition to the cost of the haircut, crashed out through the door and wended his way jauntily back to his cows.

Several days later, stories appeared in the local newspapers reporting that “an apparition of the late novelist Anthony Burgess has been seen stalking the lanes of our bailiwickâ€.

For the awful truth was that Old Farmer Frack’s “chop suey†could easily be mistaken for the preposterous Mancunian polymath’s haircut, memorably described by his biographer Roger Lewis as follows: And how are we going to describe his hair? The yellowish-white powdery strands were coiled on his scalp like Bram Stoker’s Dracula’s peruke, not maintained since Prince Vlad the Impaler fought off the Turks in the Carpathian mountains in 1462. What does it say about a man that he could go around like that, as Burgess did? Though he was a king of the comb-over (did the clumps and fronds emanate from his ear-hole?), no professional barber can be blamed for this. I thought to myself, he has no idea how strange he is. What did he think he looked like? He evidently operated on his own head with a pair of garden shears.

Egg Update

Back in November, you will recall, we had a brief look at George Orwell’s diary and its – at times – exclusive concentration on egg-counting. I have not seen fit to keep you abreast of the daily totals, confident as I am that you are equally fascinated by this egg business, and thus have added a check of the online diary to your daily routine. However, the latest seventy-year-old entry is somewhat alarming, so I thought I should draw your attention to it.

26-28.12.38 Have been ill. Not certain about number of eggs, but about 9.

Not certain? Get a grip, George, get a grip!

Tiny Enid And The Dustbin Of History

One misty morning, Tiny Enid was reading the latest issue of her favourite comic, The Ipsy Pipsy Woo, when, in a speech bubble hovering over the head of a character called the Very Reverend Prebendary Septimus Widdecombe, she came upon the words “the dustbin of historyâ€. Specifically, she learned that every now and then there were people or institutions or events that were consigned to this dustbin. Tiny Enid thought this was a very sad state of affairs, but she was not a mawkish weepy kind of girl, so she did not sob into a napkin.

A helpful footnote in the comic explained that the existence of the dustbin was first revealed by a beardy bespectacled Russian revolutionary who ended up with an ice-pick in his head. Such a gruesome fate did not bother Tiny Enid one iota, for she could herself be ruthless as occasion demanded. She was alarmed, however, to read that the dustbin might not be a dustbin but a mistranslation of ash heap. If that which was consigned to it was incinerated, she reasoned that it would be beyond salvage. For already, you see, being the impetuous infant adventuress she was, Tiny Enid had decided to find the location of the dustbin of history and to rescue its contents. This seemed exactly the kind of mission for a plucky youngster who had been twiddling her thumbs in idleness for an entire fortnight, without a single daring escapade to speak of.

Casting The Ipsy Pipsy Woo aside, Tiny Enid took down an atlas from the bookcase. It was such a huge atlas that it probably weighed more than she did, but she managed to slam it down on to her lectern. The lectern was a full size one, donated to Tiny Enid by a grateful vicar whom she had rescued from the jaws of death in the jungle where he had a bit part in a Werner Herzog film, and she had to saw off part of the base to make it just the right height for her diminutive stature. Deciding not to worry overmuch about whether the dustbin was actually an ash heap, she skimmed hurriedly through the atlas looking for places where a pretty large dustbin or ash heap might be concealed. Although neither the speech bubble nor the footnote in her comic suggested that the dustbin of history was hidden away somewhere, Tiny Enid intuitively felt that must be the case, and she often relied on her intuition, which, as she explained to those who asked her, was not feminine intuition so much as heroic club-footed infant intuition, a different kind of intuition entirely, and far more accurate. It was, after all, her intuition which led the brave tot to track down the vicar on location in the jungle with Werner Herzog rather than, say, elsewhere with a director such as Jean Luc Godard or Guy Ritchie.

Pinpointing a large, flat, windy and uninhabited area on one of the continents, Tiny Enid packed her pippy bag with supplies and vroomed off in her jalopy towards the aerodrome, terrifying geese and ducks and roadside mendicants as she drove pell-mell along the winding country lanes. Hopping into her bi-plane, she roared away, out of the mist and up into the immense blue firmament, begoggled and begloved and chewing on a radish. She thought it would be a good idea to contact her mysterious unseen mentor to let him know what she was up to. We first encountered this mentor in an earlier story where he was introduced for intricate plotting purposes, without any clear idea of his identity. No need to worry about that now, however, for when Tiny Enid reached for the pneumatic speaking funnel she realised it was clogged with dust and pebbles. Even if she did manage to get a signal, all her mysterious mentor would hear from her would be mangled mufflement. She threw the funnel aside and revved her engines with renewed derring-do.

There was much turbulence during the flight, and much turbulence too inside Tiny Enid’s head. We think of her as a self-possessed and unflappable heroine, and she was, but often that resolute exterior masked inner turmoil. Like any of us, Tiny Enid was subject to entrancements and ecstasies, to sloshes of despair and to cranial hullabaloo. Weirdly, rather than planning what she would do if the dustbin of history turned out, after all, to be an ash heap, and an ash heap in a flat windy area where the ashes would be blown and scattered, she was instead mulling over something else she had read in that week’s Ipsy Pipsy Woo. In his weekly column, Father Ninian Tweakling had set a moral conundrum. Faced with the choice, which would you save from a burning tower – a half-starved yet impossibly cute puppy, or the horned and cloven-hooved incarnation of the Devil himself? This was precisely the kind of daring rescue Tiny Enid could imagine herself making one day, but she had to discount her immediate response, which was that she would cleverly extinguish the fire, carry the puppy directly to a dog hospice, and return to save the Devil, but bind him in chains and make him promise to mend his ways. Father Tweakling made plain that there was a choice to be made, between puppy and Beelzebub, and a great moral lesson to be derived from the making of it. Tiny Enid had been turning it over in her mind for a couple of days now, and it continued to busy her brain as she soared through the sky towards where she hoped she would find the dustbin of history.

She had still not come up with an answer when she brought the bi-plane down on to a landing strip attached to an apricot pericarp testing station. From here, she would have to hike across the plains, but first she stopped in at the station and asked the fruit scientist based there to give her a cup of tea.

“Tell me,†she asked in her shrill, fearless way, “Am I right in thinking that about fifty miles west of here across the plains I will find an enormous dustbin?â€

The fruit scientist paused in his tea making, fixed the plucky tot with a watery gaze, and said, “Ah now, miss, some say as there is and some say as there ain’t. And me, I wouldn’t rightly know neither way. Milk?â€

“You speak more like a bumpkin than a fruit scientist, sir!†shouted Tiny Enid, “And yes please, milk in my tea, thank you.â€

Even though she was irritated by the fruit scientist’s semiliterate drivel, Tiny Enid never forgot her manners.

“Why might you be looking for a big dustbin all the ways out here then, little one?†asked the fruit scientist.

“Because, O man of apricot pericarps, I am resolute and intrepid,†replied our heroine.

And soon enough, as good as her word, Tiny Enid was on her way across the plains. As she thumped her way westwards, she wondered if the fruit scientist had been putting on an act in a misguided attempt to warn her off. Could the dustbin of history be a dangerous dustbin? If it was, Tiny Enid would be not cowed, she would snub her nose at it and carry on regardless, for she was frightened of nothing. She stopped at a place that was a bit less flat and windy than the rest of the plains and sat and smoked a cheroot, taking from her pippy bag the gazetteer she had packed earlier. Consulting the index, she saw that there were entries for neither Ash heap nor Dustbin but under History she found an illuminating survey of everything that had happened upon the plains for the last thousand years, from the battle of the boppityheads to the hunting to near extinction of the lopwit to droughts and floods and windiness to the establishment of the apricot pericarp testing station. It was all very interesting, and Tiny Enid lodged it in her memory banks. One day, she knew, she would no longer be tiny, and adventure would lose its allure, and she pictured herself grown and a bit dotty, sitting in a cottage writing her memoirs, and she wanted to forget nothing, for she was determined that she herself would never be dropped into the dustbin of history.

And then she sat up with a start. It suddenly occurred to her that, when she found the dustbin, and peered down over its edge, she might lose her footing and topple into it! Perhaps it had a greasy rim, or lethal uneven patches where it had been gnawed by wild animals. She rummaged in her pippy bag and blasted the heavens that she had not brought a goodly length of mountaineer’s rope and clambering hooks. Well, she had faced peril before and would face peril again. Stubbing out her cheroot and crushing it under her corrective boot, she pressed on into the west.

The sun was sinking when Tiny Enid arrived at a compound surrounded by a security fence. She smiled to herself at the thought that, though she may have neglected to bring mountaineer’s rope and clambering hooks, she never went anywhere without her razor sharp security fence slicing shears. Dipping into her pippy bag to get them, she read a sign affixed to the fence. Large Flat Windy Uninhabited Plains Municipal Hygienic Waste Disposal Chute Compound, it said. Tiny Enid stamped her club foot and let out a shrill cry. The dustbin of history was neither a dustbin nor an ash heap but a chute! This put an entirely new complexion on her adventure. To salvage those things that had been deemed historical irrelevancies, she would have to find where the chute terminated, somewhere subterranean, and she had not brought a spade. One option, of course, was to fling herself recklessly down the chute, but that would be like toppling over the edge of the dustbin. She put the shears back in her pippy bag and sat down to think. She wondered if the lesson to be learned from the answer to Father Tweakling’s moral conundrum could help her now. A burning tower, a starving puppy, the Devil incarnate, and now add a hygienic waste disposal chute…

All of a sudden, Tiny Enid knew exactly what to do. She raced back to the apricot pericarp testing station, felled the fruit scientist with a few well-aimed kicks to the head and the stomach, clamped a bleeping tracker device around his ankle, shoved him into a wheelbarrow, pushed him west across the plains, disabled the municipal compound alarm system, sliced a hole in the security fence, and dumped the fruit scientist down the chute. Popping a radish into her mouth, she snapped open the tracker device palmpod, and watched as the fruit scientist’s avatar, a cartoon head bearing a striking resemblance to Ringo Starr, tumbled, beeping, deeper and deeper down below the windy plains, tumbling and beeping, until at last it came to rest at what the coordinates told Tiny Enid was the earth’s core. So this was the dustbin of history.

Tiny Enid had attended enough geology lectures to know that the centre of the earth is a ball of ferociously hot boiling burning magnetic rock, and that pretty much anything tumbling out of a chute on to it would not survive for a moment. She knitted her brows, fretful that her daredevil mission looked set to end in failure, a word, of course, the diminutive adventuress neither acknowledged nor understood. Turning on her heel, she clumped back across the plains to the landing strip, and steered her way across the skies until she was home, and she sat at her table scoffing down a bowl of milk slops, resting her club foot on a dimity cushion. By the time she had drained her bowl, she had a plan. Part of it would have to wait until the next issue of The Ipsy Pipsy Woo came out, wherein she was sure a moral conundrum from Father Ninian Tweakling would lead her on the correct path, once she had solved it. But the other part of her plan could be set in motion immediately. Lurching over to the desk upon which her metal tapping machine sat polished and gleaming, she transmitted a message to her mysterious unseen mentor.

I must journey, Jules Verne-like, to the centre of the earth, she tapped, and clearly such an expedition will cost a bob or two. Please start a fundraising appeal immediately. Yours sincerely, Tiny Enid.

And thus did the venturesome mite’s next hectic and compelling adventure begin.

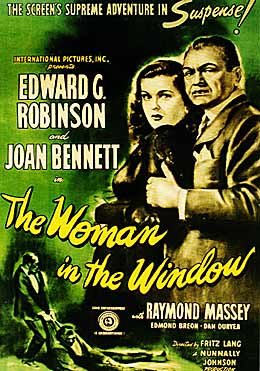

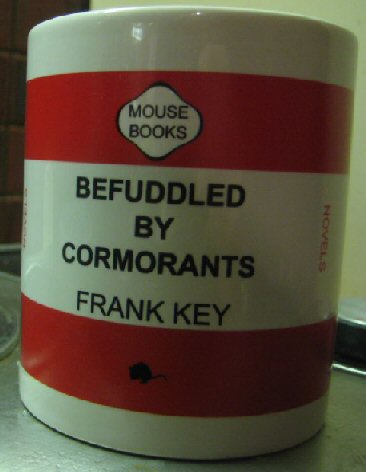

Mugshot

What Dobson Did On Boxing Day

[This piece first appeared in December 2004. How things change. Four years ago it appears that a contraption called the telephone was still in use at Hooting Yard, rather than the more familiar, and much groovier, metal tapping machine.]

Throughout his life, Dobson ignored Christmas, but he loved to celebrate Boxing Day. Every year, he made a point of marking the occasion differently. Here is his journal entry for one year during the 1950s.

Ah, Boxing Day at last! What a glorious day it is. This year there is snow on the ground, robin redbreasts hopping about, and Dickensian scenes of wassail and carousing over by the old thatched tavern. That being the case, I have nailed fast the shutters and am sitting in the gloom. I wired up a microphone next to the indoor wasps’ nest, so hectic buzzing drowns out the intolerable sound of carol-singing and suchlike torments.

I breakfasted upon a platter of boiled leeks and steamed viper-heads. I will spend much of the day in the kitchen, boiling more leeks and steaming more viper-heads for my supper. I had a new telephone installed last week, and I intend to take a break from boiling and steaming to call the police. I am going to read out my new pamphlet to the desk sergeant, or whoever answers the telephone, for it concerns police matters, specifically the legal position regarding the theft of leeks from the greengrocers’ and of vipers from the zoo. In the pamphlet, which I wrote in pig Latin, just to show off, I make a full confession to having used thievery to obtain my Boxing Day foodstuffs, and justify doing so with reference to certain historical and/or mythological figures, including Hildegard von Bingen, Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, and the Warrior King Anaxagrotax. I also make mention of the prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire as a way of throwing the coppers off the scent, should they determine to prosecute me.

At sixty pages, it may take some time to read the complete text to the police officer, so I will attach an extension cord to the telephone and drag it into the bathroom, and make my call while nestling in a tub of hot milk of magnesia. Over the past year I have bought a couple of those little blue-glass bottles every week, and should have enough to fill the bath. I will heat the milk of magnesia using Professor Tadaaki’s Submerged Iron Filament contraption, the label on which claims it can boil a few gallons of any known liquid within thirty seconds. Of course, I do not need to boil my bath, far from it. Tadaaki does not provide a thermometer, but I have one somewhere, in a cupboard, and as soon as I have completed this journal entry I shall go in search of it.

After the telephone call, the bath, and my supper, I will put the thermometer back in the cupboard and set a roaring fire in the grate. As I have no coal, nor wood, I will burn the beheaded vipers, for there are many of them and I suspect they will ignite well. I dried them thoroughly by putting them in the airing-cupboard under a pile of blankets. The blankets, incidentally, were not stolen. I wove them myself, when I was a child, and capable of weaving at the loom for hours upon end, humming old Latvian folk tunes to myself. In those long ago days I could never remember the words to the songs, except for one, and that only partially. In papa’s translation, it went like this: “There is a shepherd in the hills / There is a [something] green / But black is the crow in the [something] tree / And lightning blasts the sky / The shepherd’s lass has golden hair / She [something something] milk / But the crow has flown away, my love / And the ducks have left the lake”.

It’s time I made that telephone call.

Some of the prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire, gesticulating.

Truth And Error

“You can’t cite statements internal to a document to back up the claim that the document is inspired by God and that it is truth without any mixture of error. That doesn’t work, and it doesn’t work for reasons that are so obvious that failure to grasp them is simply childish. If that did work then all authors could just say ‘this book is inspired by God and it is truth without any mixture of error’ and be taken seriously.” – Ophelia Benson at Butterflies And Wheels.

Well, it may be childish to so aver, but Mr Key’s prose is inspired by the hideous bat-god Fatso, and it is truth without any mixture of error. Put that in your pipe and smoke it, as they say.

Hark! The Herald Angels Sing

Wishing all my readers and listeners a very happy Christmas.

From Thirty-Eight Woodcuts Illustrating The Life Of Christ, or Biblia Pauperum (ca. 1815). You can see the other thirty-seven woodcuts here.

Hospital Barge

Dotted along the entire length of the canal there are villages and hamlets. It is said that most have been sites of human settlements for thousands of years, which is a bit perplexing, as the canal itself was only dug two centuries ago. The hospital barge plies up and down the canal constantly, turning when it gets to Mudberth and heading straight back to Muckfield, never stopping except at locks. There are many locks. When a villager or hamleteer is sick, they are carted to the canalside by their neighbours and hauled aboard the hospital barge by a steam-powered crane-and-stretcher-and-pincer contraption. Once they have been cured, if they are cured, they are dumped ashore at the next village or hamlet, and have to make their own way home by land, unless, as is common, they choose to remain in the village or hamlet where they have been dumped, and thus do the canalside communities intermingle.

The hospital barge is staffed by a gaggle of homeopaths and healers and fraudsters and quacks, and the dispensary holds shelf after shelf packed with pointless potions such as Bach flower remedies and Beethoven weed remedies and Bruckner nettle remedies. There is not a single bottle of Baxter’s Sour But Invigorating Syrup to be found, let alone any cranial integument soothers or antibiotics. It is a wonder that any of the patients are ever cured, but in fairness it must be said that those dumped ashore at a village or hamlet miles up or down the canal from where they were winched aboard the barge show remarkable perkiness, and in many cases appear to be immortal. In the village of Filthwick, for example, no one has died in the last sixty years, and the gymnasium is filled with sprightly one-hundred-and-fifty-year-olds jumping about and springing and bounding and hopping and somersaulting and otherwise engaging in decidedly energetic calisthenics.

This being the canal along the towpath of which Dobson often trudged, the out of print pamphleteer could hardly resist writing about the hospital barge. But he wanted more than the view of a disinterested observer, and waited to fall sick so he could go aboard the barge as a patient. Alas, Dobson had the constitution of a large, sinewy, more or less rectangular animal with no known predators, and never suffered illness. He became impatient, standing on the canal towpath watching the hospital barge pass him by, occasionally witnessing the winching on of an agued wreck or the dumping of a revivified Pointy Towner. Eventually, the pamphleteer could wait no longer, and he took the fateful step of injecting himself with an experimental serum concocted by one of his pals down at the Cow & Pins. The fizzing hissing dapple-dun fluid smelled of rust and blood oranges, and was meant to cause harmless shuddering with all the appearance of a death rattle. In Dobson it had an alarmingly different effect, in that it provoked a mental imbalance making him petrified of boats and ships and yachts and barges, so much so that at the sight of water, even of a duckpond, he ran away screaming.

A fortnight later, when the serum wore off, Dobson learned through an article in the Canalside Gazette that the hospital barge had been rendered invisible. It, and its crew of homeopaths and healers and fraudsters and quacks, and its on-board patients, were never seen again, and nor were the many, many dead who had never been cured upon the barge, and whose final resting places are an unutterable mystery.

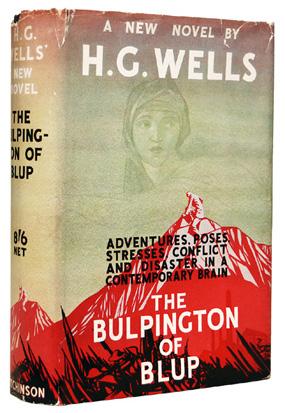

Disaster In A Contemporary Brain

I am indebted to the great Max Décharné for drawing to my attention this little-known (to me, unknown) work by H G Wells. The title is foolish enough, but I am particularly fond of that resounding subtitle: Adventures, Poses, Stresses, Conflict, and Disaster in a Contemporary Brain. Somehow I think that deserves an exclamation mark. If any Hooting Yardistas have read it, perhaps they could post a review in the Comments.

Pebblehead’s Christmas Annual

The latest victim of crunchy credit conditions is Pebblehead’s Christmas Annual, due to be published tomorrow but now indefinitely postponed. The bestselling paperbackist has been issuing his annuals every Christmas Eve for as long as anybody can remember, so this is what is known, in the language of his potboilers, as a bitter blow. Indeed, one of the features of this year’s annual was to be an exciting tale of polar tragedy called “Captain Jarvis And His Starving Huskies Are Pressed Flat Against A Glacier By The Bitter Blows Of An Antarctic Blizzardâ€. I am sorry I am not going to be able to read that to my grandchildren as a bedtime story, nor indeed to act it out in the community hub frolicking compound, if necessary using bags of flour as a snow substitute should the weather continue balmy.

As ever, the annual was to contain dozens of stories Pebblehead dashed off this past year in between writing his tremendous novels. According to the publisher’s blurb, we were promised such gems as “Vanessa Redgrave And The Revolutionary Space Cadetsâ€, “The Six Million Dollar Goatâ€, and “Ooh La La, As He Sinks Beneath The Waves, Captain Jarvis Recalls What Bliss Was It In That Dawn To Have A Mild Headacheâ€. It is something of a mystery why Pebblehead has yet to write an entire novel about this Captain Jarvis character, who gets into all sorts of exciting scrapes in all sorts of locations, exotic and otherwise. Last year’s story, “Captain Jarvis Topples Out Of A Hot Air Balloon Piloted By Richard Branson†was particularly thrilling.

We could also have expected many pictures of bees, ducks, gaping chasms, weasels, kitchen utensils, frogpersons, eggs, Ludwig Wittgenstein, cardboard boxes, giraffe heads, and tweezers. Pebblehead has been criticised for retaining the same picture categories year after year, every single annual containing three cack-handed pencil drawings of each subject, all crammed into the endpapers, but I think this says a good deal about the man. He is reliable, he is consistent, he is a bestselling paperbackist, and he can’t draw for toffee.

This year’s factual articles were to include a potted history of potted fishpastes, an analysis of sulphurous woozy barbershop quartet demons, an annotated diagram of Christ’s wounds, and a reprint of Pebblehead’s classic pig paragraph.

Add to that the quiz and the cut-out board game and the coating of scum upon the dust jacket, and it is clear we shall all be bereft at this time of otherwise unbridled jollity.

Siege Duck

Next time you and your pals need to lay siege to a fort or a citadel, why not make use of a siege duck?

Glyn Webster kindly alerted me to this contraption, which appears on Rudy Rucker’s blog.

Meetings With Remarkable Owls

Dobson’s pamphlet Meetings With Remarkable Owls (out of print) is a curious work. Ostensibly, it is a simple account of a walk he took through the owl sanctuary at Scroonhoonpooge, and of the owls he came across there. Given the unfathomable depth of his ornithological ignorance, one is tempted to suggest that the pamphleteer only knew the birds he “met†were owls because of the big neon signage at the gate of the sanctuary.

More remarkable than the owls themselves, surely, is the fact that Dobson was able to get anywhere near them in the first place. Ever since the so-called Inexplicably Spooky Events that centred on Scroonhoonpooge Farmyard, the entire area had been cordoned off by a massive security fence patrolled by wolves and wild hogs. There had always been talk of the eerie barn and the mutant albino hens and the disturbing well, to say nothing of the farmyard itself, but after what happened on that wild and windy October weekend, so great was the terror in the surrounding villages that the fence was erected overnight, and the wolves and wild hogs let loose around the perimeter.

Dobson says nothing of this. We are asked to believe that he was out and about pounding the countryside one day when he found himself at the gate of the owl sanctuary and decided to investigate. This cannot be right. To get to the gate, he would first have had to find a way through the security fence without being savaged by wolves or wild hogs, then have had to cross the perilous bogs, avoid the piano wire strung across the pathways, clamber up the impossibly steep sludge banks, find his way through the mist-enshrouded field riddled with concealed pits in which killer spiders lay in wait, and pass through the notorious spinney of poisonous trees. Even had he accomplished all that, he would somehow have had to persuade the sentries at the owl sanctuary gate that he was a bona fide visitor, or they would have shot him on the spot and buried his corpse where it would never, ever be found. The sentries were hand-picked, undergoing rigorous psychological testing to flush out any who had a less than fanatical protective instinct towards owls.

Dobson was not a particularly boastful man, but he did have an operatic diva’s sense of drama, and it seems scarcely credible that he would let pass the opportunity to prattle on about so death-defying a journey. So we must be grateful for the research done by indefatigable Dobsonist Ted Cack, whose recently published paper suggests that some weird properties in the atmosphere around Scroonhoonpooge Farmyard may have actually modified Dobson’s brain, one such modification being a complete wiping clean of his memory between eating a choc ice at the ramshackle kiosk adjacent to Sawdust Bridge and arrival at the gate of the owl sanctuary three days later.

Some traditionalists have had harsh words to say about Ted Cack. After all, he made his name as a young firebrand with a deliberately provocative book arguing that Dobson was not the true author of the Bilgewater Elegies and that the pamphleteer had never set foot in Winnipeg, let alone worked there as a janitor in an evaporated milk factory. These were, and are, preposterous theories, and Cack did himself no favours with his shoddy scholarship, cavalier approach to source material, and pomposity. Yet with his Anthony Burgess hairstyle, hornrim glasses, and barking voice he was a natural for television chatshows, and even the crustiest Dobsonists still speak in awe of his legendary appearance on Russell Harty Plus. TV critic Loopy Sebag wrote at the time that “Ted Cack, with his Anthony Burgess hairstyle, hornrim glasses, and barking voice, is the best thing I have ever seen on television, apart from It’s A Knockoutâ€.

In his attempt to unravel what happened to Dobson on the day of his visit to the owl sanctuary, Ted Cack put himself in the pamphleteer’s sturdy Hungarian Flying Officer’s boots, and recreated the journey. Of course, Scroonhoonpooge is much changed. The whole area around the farmyard has been flattened, and there is no longer any sign of the eerie barn or the disturbing well or the albino hens or indeed of the owl sanctuary. In their place stands a derelict and abandoned shopping precinct in which feral beasts and teenagers cavort and carouse. Only a branch of the plumbing chain Spigots R Us remains open, and its stock is covered in dust and breadcrumbs. Characteristically, Ted Cack was undeterred. He had read a lot of books about psychogeography, and though he did not really understand what he read, he was determined to pretend to be the pamphleteer in that place at that time on that day so many years ago, so much so that he prepared by eating a breakfast of bloaters and wearing a grubby pair of trousers. And, just as the painter Oskar Kokoschka had a life-size rag doll made to replace his lost love Alma Mahler, Ted Cack created a simulacrum of Marigold Chew using string and wool and scrunched-up dishcloths, and waved it goodbye as he crashed out of the door on his way to Sawdust Bridge.

The crucial paragraph in his research paper is this:

There I stood, he wrote, in a puddle outside a boarded-up milk bar where once had stood the gate of the Scroonhoonpooge Owl Sanctuary. I had absolutely no idea how I got here. It was as if my brain had been modified in some sinister way and my memory wiped clean. This leads me to the irrefutable conclusion that exactly the same thing happened to Dobson, and that is why he never wrote about his perilous journey in his pamphlet Meetings With Remarkable Owls (out of print). What I do not yet know is how permanent this brain modification will prove to be. God help me.

I cannot see any holes in this argument whatsoever, so I am prepared to state that Ted Cack, pompous and irritating as he may be, has solved one of the enduring mysteries of the pamphleteer’s career.

As for the pamphlet itself, as I said, it is a curious work. Trudging through the owl sanctuary, Dobson from time to time comes across an owl perched upon the branch of a tree. He attempts, first, to describe it, and this is where his lack of ornithological knowledge lets him down. Each description consists almost entirely of the words head, beak, wings, big round eyes, talons, and hooting sound in various combinations. But it is the second part of each “meeting†to which we turn, wherein Dobson tries to, as he puts it, “commune with the owlsâ€. He hoots at them. He flaps his arms as if they are wings. He pounces upon a squirrel or a fieldmouse and savages it and swallows it. He hoots again.

I am Dobson, he writes, and for today at least, I am become an owl.

It is, I think, not the owls which are remarkable in this instance, but Dobson himself.