Conducting my regular Hooting Yard Prose Audit, I was dumbstruck to discover that only once have I written about fubbed pannicles, and that was five years ago. In lieu of anything new to say about this most important of topics, here is a timely repost.

In an appreciative review of the second, expanded edition of Harmonium (1931), R P Blackmur remarked that “the most striking if not the most important thing” about Stevens’s verse was its vocabulary, a heady confect including such rarities as “fubbed”, “girandoles”, “diaphanes”, “pannicles”, “carked”, “ructive”, “cantilene”, “fiscs”, and “princox”.

From Wallace Stevens : Metaphysical Claims Adjuster by Roger Kimball, collected in Experiments Against Reality (2000)

It was a dark and stormy night. Off the Kentish Knock, on the wild and churning waters, the HMS Whither Art? was being tossed about like so much flotsam. The ship’s captain, Captain Plunkett, was all too aware that it was here off the Kentish Knock on a similarly dark and stormy night in 1875 that the SS Deutschland had been wrecked, and five Franciscan nuns, including a peculiarly tall one, had suffered death by drowning. Captain Plunkett had no Franciscan nuns aboard his ship, unless there were stowaways of whose presence he was ignorant, but well he knew the HMS Whither Art? was in equal danger of wreckage on so dark and stormy a night. It would take all his mastery of the nautical arts to bring the ship and its crew safely through to dawn, and port.

Clinging to the wheel, he cried out for the first mate, First Mate Hoon. Weedy and neurasthenic yet impossibly valiant, Hoon came staggering on to the bridge. He was sopping wet, drenched by both the teeming rain and by sloshing seawater.

“Hoon!” yelled the captain over the howling gale, “It has suddenly occurred to me that we may have stowaways aboard of whom I am ignorant, nuns, Franciscan nuns, hiding in the pannicles! Detail a detail of deckhands to search every last inch!”

“Aye aye, captain!” yelled Hoon, “But I’ve just had a report over the ructive hooter from the princox that the pannicles are fubbed!”

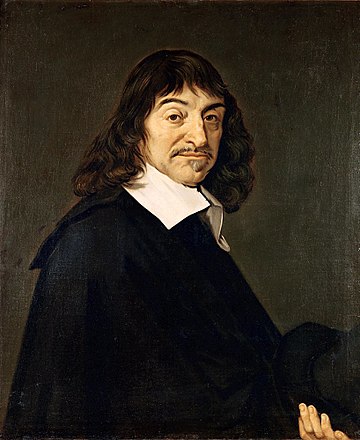

Captain Plunkett took one hand off the wheel, curled it into a sort of perch, turned it towards his head, and bent forward, resting his mouth and chin on his hand, striking an attitude almost identical to Rodin’s Thinker. He was thinking. He was thinking how it could have happened, on his watch, that the pannicles had been fubbed. He was thinking how it had come about that he had not heard the princox’s message over the ructive hooter. He was thinking that he had completely forgotten the name of the princox. And he was thinking that, if there were any stowaway Franciscan nuns hiding in the pannicles of the HMS Whither Art?, then they would surely have been carked by the fubbing. When he had finished thinking, he lifted his head, put his hand back to the wheel, and cried aloud again to Hoon.

“Hoon! Scrub that last command to detail a detail of deckhands!”

“Aye aye, captain! I have obliterated it from my brain so rapidly and thoroughly that already I have forgotten to what the word ‘it’ refers!”

The wind continued to howl and rage, the rain to teem, the sea to slosh, and the storm to toss the ship upon the waters.

“Hoon!” cried the captain, “What is the princox’s name?”

“I know him only as Alan,” shouted the first mate, “As in Ladd or Whicker or Freeman, known as Fluff.”

“The princox is called Fluff?” cried Captain Plunkett.

“Aye, captain, by those of the crew who are radio enthusiasts.”

“Detail Fluff to man the diaphanes, Hoon!”

“Aye aye, captain!”.

And Hoon left the bridge, staggering below decks in search of the princox. The storm did not abate. The captain struggled manfully with the wheel. His head was now empty of thought. He was engaged in an elemental battle, man versus sea, or man versus storm, or better, perhaps, man versus stormy sea.

Meanwhile, on one of the decks, poop or orlop, one of the girandoles had been torn loose from its cantilene and was clattering about perilously. First Mate Hoon, making his slow unsteady way to the princox’s nest, saw what had happened and realised he had to make an instant decision. There was no time to think. He could not afford to curl one hand into a sort of perch, turn it towards his head, and bend forward, resting his mouth and chin on his hand, striking an attitude almost identical to Rodin’s Thinker. He staggered back to the bridge.

“Captain Plunkett!” he screamed, “One of the girandoles has been torn loose from its cantilene and is clattering about perilously on the poop or orlop deck!”

“Where is Fluff the princox?” cried the captain.

“Still in his nest I expect,” yelled Hoon, “For when I saw that one of the girandoles had been torn loose from its cantilene and was clattering about perilously on the poop or orlop deck, I made an instant decision to tell you about it as soon as I possibly could!”

“You should have used the ructive hooter!” cried Captain Plunkett.

“Believe me, captain, I would have done had you heard the ructive hooter message regarding the fubbed pannicles. But you did not, and I dared not risk that a second ructive hooter message would go unheard by you!”

“That shows good seamanship, Hoon,” cried the captain, “Let me pin a golden star to your cap.”

“Thank you, captain. I appreciate such recognition, it compensates for the lack of pay and the worm-riddled biscuits.”

And all of a sudden there was a lull in the storm, and the captain and the first mate looked up at the stars in the sky. For a few precious moments, the HMS Whither Art? was safe upon the sea. And down below in the pannicles, the sudden calm prompted five stowaway Franciscan nuns of whose presence Captain Plunkett was ignorant, one peculiarly tall, to pop their heads out from the rickety fiscs wherein they were hiding, and to sing a hymn of thanks to Almighty God, that He had delivered them from the fubbing.