It is hard to think of an esoteric sect more hidden, more obscure, than the Erk Gah. We know virtually nothing of its membership, its ceremonies and rituals, its raiment and vestments, its perfumes, its symbols, its armaments cache, its hierarchy, its headgear, its idiosyncratic buttoning methods, its potions, its nostrums, its pomposity, its colour schemes, its texts, its insignia, its dietary stringencies, its bucket and spade seaside outings, or its ultimate purpose. Some have suggested that the Erk Gah does not even exist.

One wonders, then, what to make of Evaporated Milk & Ducks’ Blood, the latest bestselling paperback by Pebblehead, with its audacious subtitle The Truth About Erk Gah Revealed! As ever with his ventures into non-fiction, Pebblehead’s prose is breathless and slapdash and at times laughable, but he makes grand claims, and they deserve to be treated seriously. After all, we are unlikely to get a better guide to this mysterious sect, even if it is wholly spurious.

One thing Pebblehead refuses to tell us is from what sources he cobbled his 300-plus pages together. Indeed, one reviewer has already insisted that the book ought to be shelved alongside Fantasy Fiction, that Pebblehead has made the whole thing up. But how would anybody know one way or the other, unless they were a member of the Erk Gah? It may be pertinent that the reviewer in question disguised his identity behind a terrifically-wrought anagram.

But let us look at some of Pebblehead’s claims.

Membership. The Erk Gah has a finite number of members. When one dies – of which, more in a moment – they are replaced by a new recruit. How this newcomer is chosen is an ineffable mystery. It is possible that there are as few as twelve members at any one time, although other estimates give a figure of several thousand. Erk Gah members do not die in the sense that you or I would understand the term. Instead, they are “begusted into flimflam”. Pebblehead does not expand upon this.

Ceremonies And Rituals. The major Erk Gah ceremony is the so-called “knocking about of the ball with the puck”, which as far as one can gather may look to the innocent eye like hockey practice. “Thus,” intones Pebblehead, ominously, “does the sect conceal its existence by creating a facsimile of a well-loved sport which is part of the fabric of our everyday lives, if we are sporty persons of course”. There is another ritual, involving binoculars, promontories, and seabirds, which can be equally misconstrued by the ignorant.

Raiment And Vestments. Unutterably gorgeous, according to Pebblehead, and so stylish that Erk Gah members can be mistaken for dazzling stars of the Riviera set. Apparently, there is something called the cufflink code, but the details of that, too, are an ineffable mystery.

Perfumes. The Erk Gah can be sniffed out, we are told, if one is sensitive to certain vaporous effusions. Pebblehead gets rather tied up in knots trying to explain what on earth he is babbling on about here, and the passage is dense with footnotes. At one point he suggests the scents with which the Erk Gah spray themselves are odourless, which, if true, is either foolish in the extreme or perhaps yet another of those ineffable mysteries.

Symbols. Chiefly pelicans, silkworms, bowls of alphabet soup, chunks of gack, herons, old bakelite wireless sets, dust, corks, bats, cravat pins, big fat magnetic robots, chaffinches, oildrums, pulp, song thrushes, camphor sausages, toadflax, jibs, cloudbursts, mayonnaise, tin tabernacles, blots, mist, and Herculean effort. All these things, with their deep Erk Gah significance, are depicted on a gigantic shield, carted about the countryside at dead of night, by blind devotees. Or so Pebblehead would have us believe.

Armaments Cache. The Erk Gah are fond of Howitzers, and have been known to fire them when unprovoked. If you hear a mysterious explosion in the distance, on a Thursday at dusk, that might be the Erk Gah.

Hierarchy. “There are so many levels,” writes Pebblehead, “So many, many, many levels, gosh, my head is spinning!” Novelty Pebblehead dolls with spinnable heads went on sale in toyshops as part of the publicity for the book, presumably to give some credence to this assertion.

Headgear. Less Riviera set, more grimy peasant. Shapeless, filthy rags puckered up and scrunched and plopped atop the pate. Beetles and other black creeping things scurry among the folds. They can hardly be called hats, but are made by milliners contracted individually by some kind of Erk Gah hat emissary. Whereabouts this position fits within the Hierarchy is moot. Pebblehead’s head was presumably spinning far too rapidly for him to be able to enlighten us. And was the paperbackist himself wearing a sordid Erk Gah hat as he wrote? There are, after all, plenty of corrupt milliners setting up shop in our streets, more’s the pity.

Idiosyncratic Buttoning Methods. “All this buttoning and unbuttoning!” wrote the anonymous 18th century suicide. Was he or she a member of the Erk Gah, practising auto-begustment into flimflam? Pebblehead does not tell us, probably because he doesn’t know. But he does devote an excruciating forty pages of his book to the matter of buttons and buttoning and unbuttoning and unbuttons. Excruciating, because here his prose it at its sloppiest, and it is impossible to make head nor tail of what he is trying to say. I, for one, would have been interested in the Erk Gah concept of the unbutton, for example, “that which is not, and cannot be, a button, on any possible planet”.

Potions. The most popular of Erk Gah potions appears to be a decoction of evaporated milk and ducks’ blood, hence the title of Pebblehead’s tome. This mixture is drunk from lovely goblets, or from paper cups, depending upon the alignment of the stars and the idiosyncratic buttoning method in use at the time. Where the devotees get all the ducks’ blood from is an ineffable mystery, as they seem not to approve of the slaughter of ducks or of anything else which paddles in ponds. There is another potion, of evaporated milk without the commingling of ducks’ blood, of which the Erk Gah are equally fond.

Nostrums. Pebblehead alludes to a bulky collection of nostrums which the Erk Gah are said to apply to common agues. Many of these remedies are of a purgative effect, which I am afraid conjures up the image of a troop of sectaries throwing up all over the place, and an overpowering stink of regurgitated evaporated milk and ducks’ blood. I looked up “mops” and “disinfectant” in the index, but neither word appears there. In fact, the index is a very shoddy piece of work, and I think it may have been taken from another book entirely. Pebblehead has done this before, of course, through either indolence or stupidity.

Pomposity. There is an inherent pomposity in most occult and esoteric sects, acting as a sort of protective veneer. Without pomp, the edifice might crumble, and crumblement must be avoided at all costs.

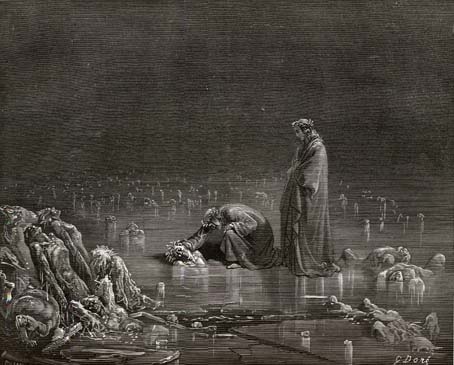

Colour Schemes. Mostly sepia.

Texts. One of Pebblehead’s most startling discoveries is that a list of the foundational texts of the Erk Gah is identical in every particular to a list of volumes stolen over a period of five years from the Tundist Owl Library. We know that the Tundists were so enraged by the thefts that they sent a gang of merciless cut-throats in search of the culprits, but the fact that the books were never returned to the library suggests that the Erk Gah, if indeed the thieves were among their number, must have outwitted the Tundist avengers. This ought not be surprising, Recent studies have shown that, contrary to myth, the Tundists were a witless and noodle-brained bunch, many of whom did not even know what an owl was, despite the comprehensive collection of owly prose in their library. But if the basic texts of the Erk Gah are indeed originally Tundist, are they a mere subsect? That is a question to which, one hopes, a writer more scholarly and less populist than Pebblehead will address themselves, though the survival rate of authors investigating Tundism is calamitously low, and much blood has been spilt, not all of it the blood of ducks.

Insignia. Pebblehead makes a cack-handed attempt to sketch the insignia of the Erk Gah on the frontispiece of his book. It looks as if he used crayons. A six-year-old would have made a better fist of it.

Dietary Stringencies. What foodstuffs, we might ask, do the Erk Gah wash down with their evaporated milk and ducks’ blood potions? The answer, according to Pebblehead, is “anything from the tuber family” and “anything with a –hip or –wort suffix”. That seems pretty stringent to me, but then I’ll eat anything, as will Pebblehead himself. I had dinner with him a few weeks ago and we scoffed a surfeit of lampreys and more bloaters than his dining table could support. He had to have it shored up with cast iron props.

Bucket And Spade Seaside Outings. An endearing feature of the Erk Gah is their predilection for bucket and spade seaside outings. Less endearing – much less endearing – is that their favoured destination is the foul and filthy fishing port of O’Houlihan’s Wharf. It is a curious place to rattle towards on the train, waving one’s bucket and spade cheerily out the window, for of course there is no sandy beach there, merely a couple of rotting jetties built upon squelchy oozing mud, mud that is home to disgusting squirmy wriggling things which are surely abominations in the sight of God. And yet year after year the Erk Gah descend upon this briny hellhole, mad with glee. What they actually do with their buckets and spades when they get there does not bear thinking about. The most Pebblehead will divulge is that shutters go up in the whelk-encrusted hovels, the streets empty, and a fug of eerie mist falls upon the port.

Ultimate Purpose. This, of course, as Pebblehead readily admits, is the final ineffable mystery of the Erk Gah. It brings his book to a limp and unsatisfactory ending, which he tries to bolster by dazzling the reader with vividness. But Pebblehead doesn’t really do vivid, at least not in his non-fiction, and the resulting closing paragraphs are pitiable. The reader senses that he knows this, which is why in a last desperate lunge at thrillsomeness, Pebblehead chucks in an extremely potted pen-portrait of his favourite pig. It is, he says, “a committed pig”.

Further Reading. A rival account of the Erk Gah, which differs from Pebblehead’s book in every single detail, can be found here.