I am indebted to reader Mike Jennings who, despite being banished to a pompous land, has, in his own words, been “compiling these tentative notes toward a Dobson bibliography”. This seems to me to be a work of magnificent scholarship. Indeed, I cannot begin to imagine how we have all been coping without it.

Mr Jennings adds “Much work is to be done of course with regard to details such as binding, font, illustration etc but I know my limitations. Such scrutiny I will leave to more qualified Dobsonists with the requisite anoraks and little grease-proof bags of egg sandwiches.”

The bibliography is ordered according to an arcane system of Mr Jennings’ own devising, one the intrinsic beauty of which I hope we can all appreciate. I have taken the liberty of applying a set of Blötzmann Numbers to the pamphlet titles. Though broadly similar to ordinary numbers, they of course harbour a terrifying underlying significance. To paraphrase H P Lovecraft, “the most merciful thing in the world is the inability of the human mind to understand the Blötzmann Numbers”.

Unless otherwise stated – and it isn’t – all titles are out of print.

1. The Adhesive Properties Of Six Hundred Different Types Of Glue, With Diagrams

2. Dobsonetics.

3. A Recantation Of Dobsonetics.

4. On The History Of Potato Clocks.

5. My Revolutionary New Method Of Moving Sludge Around The Countryside.

6. Hedges Hidden From Sight By Steam.

7. I, Piano Tuner!

8. “The hedgehog grumbling back to darkness is known by me and loved by me” (The Rod McKuen pamphlet)

9. Why I Shall Bestride This Century Like A Colossus.

10. Certain Aspects Of Plastic Baubles And Plastic Sheeting.

11. Killer Bees, Ferenc Puskas, And Tomatoes On the Vine.

12. How I Coped With A Collapsed Lung During A Thunderstorm.

13. Chew, Gnaw, Eel, Teeth, Pap And Slops For Dinner : A Memoir Of Vlasto Pismire.

14. Of the fifteen-part critical analysis of The Life and Times of Captain Cake, Volume IV is entitled Welk, Bankhead, Loy : There’ll Be A Welcome In The Hillsides.

15. Worlds Beyond Sense .

16. Chucklesome Fripperies From My Notebooks (Lavender Series).

17. Things Beginning with B, My Hatred of Squirrels, & Hedy Lamarr: Scientist.

18. How And Why I Built Eight Small Pâpier Maché Brontosauruses.

19. How I Invented a Revolutionary New Birdseed.

20. The Belle of Amherst & Other Essays Written During An Unprecedented Pea-souper.

21. Hideous Execution Practices Of The Blood-Drenched Corsairs.

22. Ten Easy Steps To Grooming Your Cormorant.

23. My Nightmares About Emily Dickinson.

24. Downy, Witched, Dutch Cloud-Heaps of Some Quaintest Tramontane Nephelococcugia of Thought.

25. Dobson’s Heraldic Dossier.

26. Marsh Gas, Badge Man, Prester John & Other Imponderables.

27. Tip Top Encyclopaedia Of Tip Top Pop Bands.

28. There’s Hours Of Fun To Be Had With A Handful Of Pins (Under the pseudonym “Blenkinsop”).

29. Description of & Reverie upon Forty-Four Curlews.

30. Some Hurried Notes On Tab Hunter.

31. Eight Things You Never Knew About Tuesday Weld.

32. Why I Do Not Live In A Grot, Elfin Or Otherwise.

33. Copse & Spinney Nomenclature : A Guide For Tiny Tots.

34. Six Types Of Snodgrass Implement.

35. On The Naming Of Curs As Fido : A Stern Corrective.

36. An Alphabetical Guide To What Every Infant Should Know About The Majesty Of Nature.

37. How My Annotated List Of Chewed Things Was Lost In A Muddy Canadian River.

38. The Bee As Moral Exemplar & Other Insect-Related Parables For Young & Old Alike, Innit.

39. Cornflakes, Ready Brek, Special K and Suicide.

40. Some Things To Eat In The Bleak Midwinter.

41. A Full And Frank Commentary On “The Dark Night Of The Soul”, Wherein Certain Controversial Theories Are Proposed Which Have Led The Author Into Fist-Fights With Sailors Outside Tough Drinking Taverns In The Marseilles Dockyards.

42. Little Stories Of Charming People To Warm The Cockles Of Your Heart.

43. Six Hundred And Twenty Uncanny Tales, Together With A Pen-Portrait Of Victoria Principal.

44. How I Was Attacked By A Flock Of Partridges At A Bus Stop While On My Way To The Potato Club.

45. Bilgewater Elegies.

46. Netherlands, Holland, Dutch – What’s That About?

47. Some Thoughts About Shabby Taverns, Cows And The 1958 Munich Air Disaster Which Wiped Out The Flower Of Post-War English Football, Although Sir Matt Busby Survived The Crash, Praise The Lord.

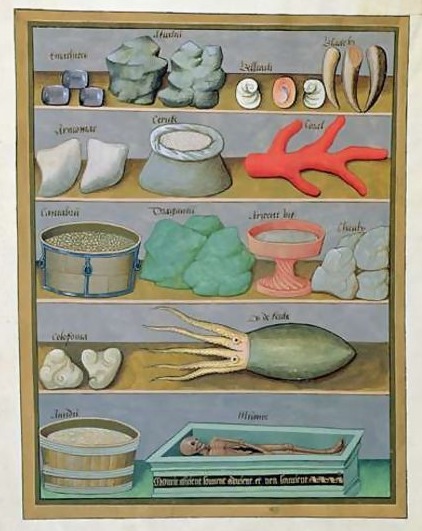

48. An Essay About Bowls, Dishes And Pots.

49. A Pamphlet Of Majestic Sweeping Paragraphs.

50. Why I Smashed My Copy Of “Thick As A Brick” By Jethro Tull Into Twenty Thousand Pieces With A Geological Hammer And Then Glued It Back Together Again.

51. Notes On A Shelf Of Test Tubes Containing The Blood Of Squirrels.

52. Observations On Cows From A Great Distance, In The Rain.

53. He Who Plucks The Strings Of A Banjo In Wintry, Wintry Weather.

54. Ten Things Guaranteed To Drive Marigold Chew Crackers.

55. Nomenclature of Paraguayan Bandit Musicians & Soviet Collective Farm Administrators Compared.

56. All About My Nocturnal River Trip In The Government Canoe With Captain Vargas, During Which I Was Heavily Sedated.

57. My Parents Are Dead, But Christ!, I Adore Hiking.

58. The Death Of Stalin Has Led Me By Dense Entangled Byways To The Unshakeable Conviction That A Complete And Thorough Pedagogic System Can Be Based Entirely Upon My Own Pamphlets.

59. How I Thwarted My Cacodaemon With A Pointy Stick And Some Bleach.

60. God Almighty, Is There Anything More Satisfying Than A Well-Executed Picnic?

61. A Dictionary Of Squirrels (and its appendix Eerie & Macabre Picnic Praxis).

62. A Dictionary Of Guillemot Habitat Maps.

63. Wild And Unhinged Fantasies Regarding The Existence Of Wholly Imaginary Registers.

64. Why I Can Be Difficult And Self-Centred.

65. The Sane Person’s Guide To Swearing By The Etruscan Gods.

66. Child, Be Thunderstruck As Your Tiny Brain Copes With The Notion That Ice And Water And Steam Are But Different Forms Of The Same Substance!.

67. Why Those Let Loose From Mad Cabins Should Immediately Up Sticks And Settle At A Seaside Resort.

68. “On terrifying facial expressions”.

69. Meetings With Remarkable Owls.

70. “On the forest beings”.

71. The Unutterable Chaos Caused By Panicking Hens.

72. My Mysterious Day Trip To Alaska And What I Did With A Handful Of Pebbles While I Was There.

73. How To Knit Knots While Remaining Invisible To Hurrying Brutes.

74. Tips For Janitors.

75. On the History and Origins of the Fred Jessop Cup.

76. A New And Improved Method Of Drying Your Puck With A Towel.

77. Some Arresting, Diverting, And Frankly Sensational Factoids Regarding Certain Ponds I Have Had The Pleasure To Take A Turn Around, In All Weathers, Arranged In Alphabetical Order By Pond Name.

78. How I Spent Six Months Underground In An Amazing Subterranean Vault Built To House The Blister Lane Gasworks, Together With Mr And Mrs Pan And Their Cat Hudibras. (considered lost)

79. An Essay Concerning A Bird Perched Upon A Promontory.

80. A Disquisition Upon The Various Types Of Cloth From Which Trousers May Be Woven , Together With Some Pictures Of Hume Cronyn.

81. How I Conquered My Fear Of Googie Withers, Together With A Few Tips On The Limitless Possibilities For Entertainment Afforded By A Toy Squirrel Made Of Tin.

82. Fun With Paraffin!

83. How To Dye A Goat.

84. What Planet Does Jeanette Winterson Live On?

85. On The Judicious And Non-Repeating Deployment Of Pancake Hints.

86. Thousands Of Unusual And Arresting Facts About Birds.

87. The Huddled Shapelessness Of The Dead.

88. How I Poked A Pointed Stick Into A Hedge.

89. Mawkish Fables Of Punctilio And Rectitude For Tiny Tots.

90. Never Pack A Knapsack In A Panic.

91. Keeping Cutlery Aligned Tidily In The Cutlery Drawer As An Absolute Imperative If One Aspires To Be Fully Human.

92. The Happy Sprinter : An Eye-Witness Account Of The Training Schedule Of Fictional Athlete Bobnit Tivol Under The Direction Of His Coach, Old Halob.

93. Tacky To Goo : Some Frightfully Complicated Thoughts On The Consistency Of Manufactured Pastes.

94. Ten Short Essays On Chopping And Cutting And Hacking.

95. Some Remarks On The Grotesque Pallor I Encountered This Morning In My Shaving Mirror.

96. The Four Horsemen Of The Apocalypse… Or Were They?

97. How I Mislaid My Bus Pass During A Thunderstorm.

98. An Anthology Of Disastrous Hiking Mishaps Cobbled Together From A Lifetime Of Ill-Starred Rustic Pursuits.

99. Forty Visits To The Post Office.

100. Six Lectures On Fruit.

101. Where Eagles Dare.

102. The Man Who Put The Bee In Beelzebub.

103. An Anecdote About Channelling Jungle Demons Wearing A Copper Cone Atop My Head While Hiding In A Cubby Full Of Bats.

104. Quite A Few Things I Know About Swans.