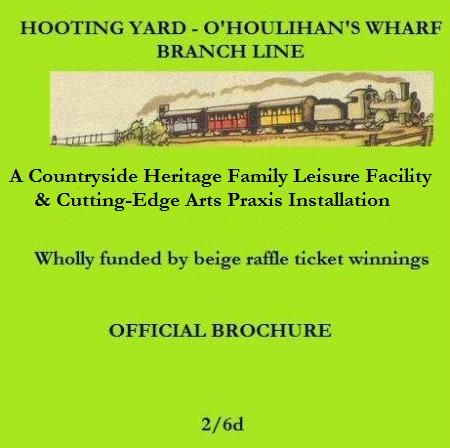

Today there is cause for celebration. No, not the Muggletonian Great Holiday, that was last week. The reason for unbridled cheer is that what you are reading is the one thousandth postage at Hooting Yard since the site was rejigged at the beginning of 2007. (I cannot recall precisely how many postages appeared in the old format, to be found in the 2003-2006 Archive, but if memory serves it is something in the region of 950.) A milestone to be celebrated, then – but how?

Ideally, you lot would cancel all other engagements, put your feet up, and spend the rest of the day rereading all one thousand postages, in chronological order, making notes in your jotter, pausing occasionally to stare out of the window as you mull over a particularly arresting item, and generally wallowing in the sheer Hooting Yardiness of it all. Always remember that a day devoted to Mr Key is never a wasted day. However, I am sensible enough to realise that most of you will have other things calling on your attention, such as feeding the hamster, waiting at the bus stop, smoking, genuflecting, pootling about, milking the cows, rummaging in the attic, taking your pills, repairing the fence down by the drainage ditch, tallying up the entries in your ledger, doing the dishes, spreading jam on bread, clutching at straws, embarking on a perilous journey downstream by kayak, grovelling in filth, putting the spuds on, intoning spells against the pestilence, mucking about, boiling your shirts, describing an arc parallel to the surface, dusting the mantelpiece, rekindling that lost love, chopping celery, going for gold, doing the odd bit of trepanning, squeezing out sponges, cutting up rough, vomiting, preening, polishing your shoon, checking the gutters, making hay while the sun shines, piling Ossa upon Pelion, folding your towels, voting with your feet, remembering a childhood idyll, splitting an atom, clocking in, lurking in the shrubbery, gathering your wits, burning an effigy, being Ringo Starr, toiling to no purpose, making whoopee, burgling the Watergate building, casting the runes, mesmerising a duck, emptying the bins, licking some stamps, darning a hole in your pippy bag, crunching numbers, thwacking a bluebottle, going rogue, distributing alms to paupers, looking shifty, holding out a glimmer of hope, pole-vaulting, caterwauling, playing pin-the-paper-to-the-cardboard, rinsing lettuce, closing the barn door, glorying in crime, sticking to the point, feeling off colour, pondering the ineffable, gargling, straining, wheedling, pining, flailing, and lying crumpled and woebegone and exhausted and hot-in-the-brain. You may have to do all of these or none, but in either case the chances are that you will be unable to devote your every waking hour to Hooting Yard, even though you yearn to do so. We shall have to come up with some other form of celebration.

It is at times like these a person’s thoughts turn to cake. It will have to be an enormous cake, to fit a thousand candles on to it. Think of all that burning wax!

I shall leave you with that thought, and press on. One could, of course, throw a party. Invite a thousand guests, and have each of them commit to memory, for party-piece recital, the text – or, as bespectacled postmodernist Jean-Pierre Obfusc would say, the discourse – of one Hooting Yard postage (including this one). The drawback to this otherwise fantastic scheme is that some postages run to thousands of words, whereas some, very occasionally, have been wholly pictorial, other than the title. Allocating all one thousand to the satisfaction of every single guest is a task fraught with difficulty, and is unlikely to be achieved without conflict and, indeed, fist-fights. Now, incidents of physical violence are not unknown among the readership. Even the surprisingly numerous Hooting Yard devotees of the Mennonite faith engage in punch-ups from time to time. Don’t even go there, as the airheads say. Taken all in all, I am not sure the party is such a good idea. Anyway, where would you fit so many people? They would not all fit into your chalet or hovel or well-appointed yet curiously pokey high-rise urban living pod, and rental fees for barns and disused aeroplane hangars have gone though the roof, according to what I have been reading in So You Want To Rent A Barn Or A Disused Aeroplane Hangar, Do You, Chum? magazine. (It’s interesting to note, by the way, that the late Harold Pinter was on the editorial advisory board of this threatening, sinister publication.)

Cake, burning wax, and party all proving prohibitive, what are we to do? Well, in extremis, one can always turn to Mrs Gubbins for some outré ideas. For once in her life, the octogenarian crone is not helping police with their inquiries, in spite of that dodgy business with the pile of mysteriously bleached bones and the trained vulture, and she is to be found snugly ensconced in an attic room at Haemoglobin Towers, furiously unravelling tea-cosies. Where once she did knit, now she unravels. By heck, there will be a glut in the used wool market by the time she is done! It is possible this is part of yet another criminal scheme, but if so it is one that is far too complicated for my puny and innocent brain. Best to ask no questions, and leave La Gubbins to her unravelling. I popped my head in to her sanctum, though, just to ask if she had any bright ideas for a Hooting Yard Thousandth Postage celebration. She looked up, fixed me with that unnerving gaze, like a blind person looking at a ghost, and pronounced the single word “Nobby”. Then she went back to her unravelling.

It was difficult to know what to make of this. The only Nobby that sprang to mind was Nobby Stiles, the popular Manchester United and England midfielder of the 1960s. His joyous capering on the pitch after England hoisted the Jules Rimet trophy in 1966 had captured the imagination of the press in those more seemly times, so perhaps that was what Mrs Gubbins was recommending – joyous capering on a field of grass. Or was she suggesting that I should enlist Nobby Stiles to help with planning a celebration? It seemed unlikely, though not of course impossible, that the retired footballer was a Hooting Yard fan, but even if he was, I did not know him, had never even collected his autograph when I was a tot, and had no idea how to get in touch with him. I entertained the thought that perhaps the crone had said “knobby”, with a K, meaning that which is characterised by having knobs, or the quality of knobbiness, such as, for example, a gnarled tree-trunk, or the backs of certain kinds of toad, but that seemed even more unfathomable. La Gubbins being the kind of woman she is, it is likely that her pronouncement was a sweeping one, containing all possible meanings of “(k)nobby”, with and without a K, plus additional meanings thus far unrevealed to the common timber of humanity. But I am afraid I had to dismiss, as wildly impractical, the idea of getting Nobby Stiles, and perhaps some other lesser-known Nobbys, to assist me in arranging a celebratory caper, of people and toads, round and round a tree in a field, much as it was appealing.

It was back to square one, and as we all know, deep in our hearts, the question always to be asked at square one is “What would Dobson do?” The beauty of the question is that if we are able to arrive at a half-way sensible answer, we know the guidance given will be infallible. Working out a valid Dobsonian response, however, is to blunder along a path strewn with nettles and serpents, unless of course one is satisfied with the generic answer “Write a pamphlet!”, which is, admittedly, correct ninety-nine times out of a hundred. Even in the present case, I can think of few methods of celebration more apposite than that every one of my readers should sit down at their nearest escritoire and pen a pamphlet. But think of the logistics. Someone would have to collate all the screeds, typeset them, print them, and distribute them to an uncaring world. I try my best to retain an attitude of breezy optimism, but I cannot see it happening. And I have not seen any vans driving past recently announcing, from the lettering on their sides, that they are in the business of Pamphleteering Solutions.

But “Write a pamphlet!” is not, invariably, the answer to the question “What would Dobson do?” Very, very occasionally, by deep analysis of the question, exercising the brainpans to their fullest extent and beyond, a different answer is revealed. To find out what this is we need to have an encyclopaedic knowledge of the complete Dobson canon, and to have pieced together as much biographical information on the out of print pamphleteer as we can, not excluding rumour, hearsay, tavern mutterings, and wild surmise. That is why I put the question to Aloysius Nestingbird, who knows more about Dobson than anyone else alive. As it happens, Nestingbird is only barely alive, following a calamitous bobsleigh accident. Quite what a frail ninety-two-year-old was doing plunging down the Caspar Badrutt Memorial Perilous Ice Declivity at the Pointy Town Antarcticorama is a question for the bigwigs at the Fédération Internationale de Bobsleigh et de Tobogganing, who I understand have already empanelled a Board of Geriatric Investigation to be headed by the fiercely independent, because ignorant of bobsleigh matters in general, Ant, or it might be Dec, the taller of the pair, the one with the glassy eyes of death.

Anyway, I bluffed my way into the clinic where Nestingbird languishes, using the techniques prescribed by Blötzmann in his Methods Of Dissimulation To Be Employed When Entering Restricted Medical Facilities (Second Series), an invaluable work which I always carry with me, just in case. Nestingbird was almost invisible beneath a panoply of tubes and wires and monitors and bleepers and what have you, but I ripped them out of my way and put my mouth to his still-bloody, gored ear, and put to him, in a dulcet whisper, the question. I want to arrange a celebration of the thousandth Hooting Yard postage. What would Dobson do? Nestingbird groaned, and some sort of despicable fluid bubbled out between his bloody lips, but he managed to tell me the answer, albeit in a croak so weak I barely heard it. But hear it I did. He said “Nobby”.

Returning home via the funicular railway, I racked my brains to see if I could wring any sense from this. Put in my position, it appeared, Dobson would “do Nobby”, or, I suppose, “do a Nobby”, as if that made any difference. Neither was a phrase I had ever heard before, and nor had any of my fellow-passengers, whom I badgered about it, growing, I am ashamed to say, rather hysterical, to the point where I was bundled off the train as soon as it reached the base station and taken round the corner, past snow-covered shrubbery, and handed over to Detective Captain Cargpan and his toughs. It is lucky for me that Cargpan is a fanatical devotee of Hooting Yard, otherwise I feel certain I would have ended up back in the clinic, and in a much worse state than Aloysius Nestingbird. Instead, the doughty copper let me off with a mussing of my tremendous bouffant. He didn’t know what “doing Nobby” was, either.

I had the sinking feeling that if I sought advice from anybody else, from born-again beatnik poet Dennis Beerpint, for example, or from Old Farmer Frack, I would get the same response. When I eventually arrived home, I made a cup of tea and heated a couple of smokers’ poptarts. Perhaps the celebration would have to wait upon the two-thousandth postage. Or perhaps I should be grateful for my simple snack. I sat down at the table, slurped the tea and shovelled down the bitter poptarts. Was this, after all, “doing Nobby”?