Cyclops With A Broom!, Dobson’s pamphlet on the one-eyed crossing-sweeper of Sawdust Bridge, is one of his very few efforts to address the subject of one-eyed crossing-sweepers. With Sawdust Bridge, of course, he was on more familiar turf, having written a full account of this crumbling yet still majestic structure in A Full Account Of Sawdust Bridge. It is a tragedy of colossal proportions that both these pamphlets are now out of print.

My own pamphlet-in-the-works, A Tragedy Of Colossal Proportions, is an attempt to come to grips, once and for all, at long last, without fear or favour, in the nick of time, huncus muncus, no holds barred, warts and all, in sickness and in health, do or die, with all due respect, up to a point, now or never, come hell or high water, with the precise lineaments of the pamphleteer’s working methods during the composition of the first mentioned pamphlet, the one about the one-eyed crossing-sweeper of Sawdust Bridge, the one entitled Cyclops With A Broom!

I have been fortunate enough to gain access to certain papers, once thought consumed in the conflagration which laid waste the Potato Building at exactly the same time as, yet decisively unrelated to, the Tet Offensive. The authenticity of these papers has been questioned by preening young Dobsonist Ted Cack, on a number of television chat shows, some of them still available for viewing on the iTarbuck and similar devices. I have addressed every single one of his pernickety little fiddle-faddles, in the pages of several journals, learned and unlearned, and also by employing a trio of rough tough ne’er-do-wells to lie in wait for him at dusk and to have at him with clobberings. It was perhaps somewhat mischievous of me to arrange for this twilit ambuscade to take place on Sawdust Bridge. I wanted to leave young Ted Cack in no doubt as to who had engineered his clobberings, without him having any proof. I wanted, as politicians are so fond of saying, “to send a message”, and equally, I wanted to ensure that for young Ted Cack, and as politicians are also so fond of saying, “lessons would be learned”. I think I succeeded in these ambitions, for there has been not a whisper from within the walls of the clinic wherein the upstart Dobsonist languishes, hovering in that unfathomable realm betwixt life and death.

It was that very realm Dobson was to probe as he struggled with the writing of Cyclops With A Broom!. His first encounter with the one-eyed crossing-sweeper of Sawdust Bridge came about when Dobson was skim-reading an article in Monocular Factotum magazine, a back number of which he found discarded in a dustbin near a splurge of lupins on the towpath of the filthy canal. Sprawling on a bench to rest his weary legs, the pamphleteer leafed through the tatty, damp pages to pass the time. He describes what sparked his interest in one of the papers I have access to, and which Ted Cack says is counterfeit, a scrap torn from a seed catalogue in the margin of which Dobson scribbled

Sawdust Bridge crossing-sweeper. One eye. By all accounts hovered in that unfathomable realm betwixt life and death. If true, of brain-numbing significance. If not, pish! Investigate with a view to writing a pamphlet.

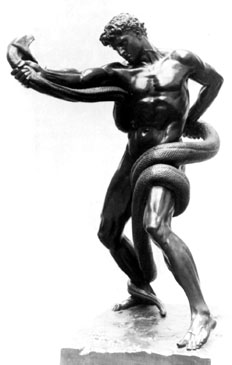

The story of the one-eyed crossing-sweeper of Sawdust Bridge which appeared in the magazine, and which Dobson was to plagiarise, fatuously, in his pamphlet, was one which had apparently transfixed the citizens of Pointy Town for a few short weeks in the nineteenth century. This “Cyclops with a broom”, as Dobson dubbed him – though why he added an exclamation mark is anybody’s guess – was a shabby yet sinister figure who appeared on the southern side of Sawdust Bridge, armed with a broom, sweeping, sweeping, on a muggy summer morn in 1861. He neither spoke nor responded to others’ speech, seemed impervious to the heat, was unresting, and swept the crossing by the bridge, back and forth, from dawn until dusk. He appeared again the following day, and for a further six days thereafter. On the next day, there was no sign of him, nor did he ever appear in Pointy Town again.

Again, in the papers, this time on a shred of Kellogg’s cornflakes carton, Dobson pinpoints the nub of the matter, as he frets with the best way to approach the tale, short of outright plagiarism, a temptation he was, alas, unable to resist.

This broom-wielding Cyclops business. Alive or dead? Man or spectral being from that unfathomable realm betwixt life and death? How to winnow wheat from chaff? Enter realm myself, via sortilege and traffic with wraiths and mumbo jumbo? Or could just copy out magazine article word for word, and change some of the adverbs.

As we know, Dobson chose the latter course. It was his unmasking as a plagiarist, and his insistent denial of guilt, that led directly to that whole sorry interlude in the pamphleteer’s career popularly known as the time of “the watercress infusion”, not to be confused with the Robert Ludlum potboiler of the same name.

But as I have pored over the scrap torn from a seed catalogue and the shred of a Kellogg’s cornflakes carton, I have become ever more convinced that, before resorting to copying out verbatim the Monocular Factotum article and changing some of the adverbs, Dobson did actually enter into that unfathomable realm betwixt life and death by means of sortilege and traffic with wraiths and mumbo jumbo. It is an astonishing tale, of pamphleteering on the brink of reason, and one which I hope to present with great flourish in my own forthcoming pamphlet. The world is waiting.

There is a possibility that young Ted Cack may be restored to health and discharged from the clinic before my pamphlet hits the airport bookstalls. If so, I want to announce here and now that there will be neither a jot nor scintilla of truth in the charge the callow upstart will lay at my door, that I have plagiarised entire, changing some of the adverbs, every last word of my pamphlet, by simply copying out his own unpublished research paper.