Brand Upon The Brain! (2006)

Brand Upon The Brain! (2006)

Brand Upon The Brain! (2006)

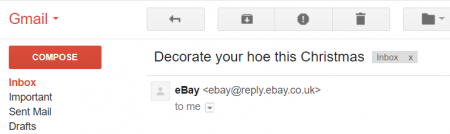

Received in the post, seasonal tips for gardeners, peasants, and yokels from those lovely people at eBay.

Sombra Dolorosa (2004)

Those who grew up in Sibodnedwabshire are forever haunted by memories of its piggeries, in the shadow of those Blue Forgotten Hills. The hills may be – oh mercifully! – forgotten, but the piggeries are not. Consider the song, still sung, or croaked, by aged decrepit Sibodnedwabshireites in the cobwebbed rumpus rooms of their hospices:

The hopes and fears of all the years

The cutman with his rusty shears

The orphans wet behind the ears

Oh swine of Sibodnedwabshire

It is not a pretty song.

There were a dozen piggeries in all, each penning dozens of pigs, except for the one that was empty of pigs, the one everybody remembers with a shudder, its piglessness both eerie and ridiculous. There was mud there, of course, mud aplenty, but not a single pig to wallow in it. The only things living in that mud were worms, tiny wriggling albino worms, worms from a child’s nightmare.

Wormy nightmares, but piggy dreams. So many dreamers dreaming of those remembered pigs in the piggeries that there is now a clinical term – PTSD, or Pig-Themed Sibodnedwabshire Dreaming. In their dotage now, those who were long long ago the tots of Sibodnedwabshire have their hospice pillows embroidered with pig motifs, the better to prompt their dreams.

What of the cutman, with his rusty shears? He would fly in, over the Blue Forgotten Hills, every Sunday, in his biplane, and come into land at the aerodrome. Accompanied by the Shire Stymonsieur, he would tour the twelve piggeries, yes, even that eerie and ridiculous pigless piggery, bandying his shears, encrusted with rust, and singing his song.

I am the cutman, come to the shire

My heart as hot as an Elmo fire

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

Oh swine of Sibodnedwabshire

It was not a pretty song.

Archangel (1990)

Oi, you lot. Mr Key has just popped out to a kiosk on an errand, and while he’s gone I want to have a quick word with you.

In a few weeks’ time, we will be marking the birthday of gentle baby Jesus, who grew up to become Christ Our Saviour. People celebrate the occasion, not by prostrating themselves before the old rugged cross and begging for the Lord’s mercy, but by giving each other presents. Being a git, I do not quite understand this, but that’s how it is.

And that being the case, what better gift could you lot give your loved ones than a Hooting Yard paperback? Imagine their Christmas morning glee when, expecting socks or piffle, they unwrap from its wrappings a book cram-packed with sweeping paragraphs of majestic prose by Mr Key!

If you go to the main page and cast your eyes over the sidebar you will find no fewer than nine paperbacks to choose from, plus a hardback and an ebook. That is eleven happy friends and family members who will have their noses stuck in a book on Christmas Day!

Meanwhile, do not forget poor scribbling Mr Key himself. All year he has been bashing out this stuff for your entertainment and moral edification, and you have been able to read it free of charge. Why not show your appreciation by making a donation, either a one-off pittance or a regular monthly amount? You’ll find Paypal links in the sidebar below the books.

Be sensible. And a very merry Christmas to you all.

The Hooting Yard Duty Git

Odin’s Shield Maiden (2006)

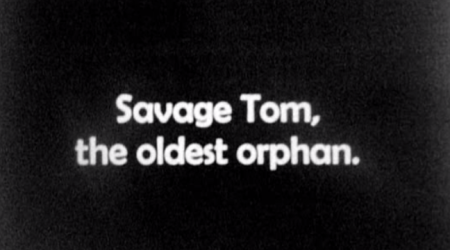

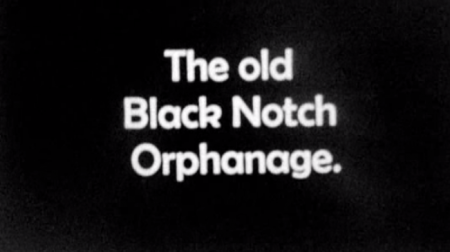

This year our Advent Calendar features intertitles from the films of Guy Maddin. Here at Hooting Yard, we revere Maddin, the finest living film director and a true original. Many of his short films are available on YouTube, and you are urged to go and watch them at once. His feature films make pretty much everything else in the cinema look impossibly dull and formulaic. Maddin is prolific – I could quite easily have chosen twenty-five different intertitles for this calendar. Perhaps next year …

Today’s intertitle is from Odin’s Shield Maiden (2006).

Hot off the possibly magnetic etherwaves, in today’s episode of Hooting Yard On The Air, Mr Key turns his attention to Little Bo Peep, hendiadys in Mudchute, a spot of juvenilia, an account of the day he forgot his own head, and the ghost of Doris Stockhausen. With luck, Miss Blossom Partridge’s Knitting Half-Hour will be back next week.

One of the more curious episodes in the life of the out of print pamphleteer Dobson is recounted in his autobiographical pamphlet 17 Years In An Alpine Mist (out of print). It begins as follows:

One day in the 1950s I was hiking in the Alps, researching all things goaty for a pamphlet I planned to write, provisionally entitled All Things Goaty In The Alps. All of a sudden I found myself engulfed in an Alpine mist. It was thick and swirling, the sort of mist one might find enswathing the three witches in a production of Macbeth, or in a film by Guy Maddin. Unable to see ahead of me, I blundered about, hopelessly lost.

I had my Alpenstock, and a flask of vitamin-enhanced boiled buttercup ‘n’ watercress water. Treading carefully, I tried to make my way down from the mountains. But no matter which way I turned, I seemed always to be going uphill, up, up, and up. The mist grew thicker and swirlier.

In prose that grows increasingly hysterical, even hallucinatory, the pamphleteer reports that several hours pass, with him plodding ever higher into the Alps. He can barely see more than an inch or two in front of him, so dense is the Alpine mist. Eventually, he comes to a halt when his path is blocked by a doorway.

The door was wooden, mahogany by the looks of it, and set within a base and brickish wall. I could see very little of the latter, in the thick and swirling Alpine mist, so I had no idea how high it was, nor how far it extended on either side. Nonetheless, I gained the distinct impression that I was standing outside a sort of half-size replica of the Winnipeg evaporated milk factory where, long long ago, I had worked as a junior janitor. This was most perplexing.

Dobson takes a glug from his flask, and then thumps his Alpenstock on the door, thrice. As if in a scene from a Hammer horror film, the door slowly opens, with an eerie and ominous creak. The pamphleteer steps inside, and is disconcerted to note that the mist is even thicker, though a bit less swirly. The door, of course, swings shut behind him, as in one of those films.

My bafflement that the indoor mist was even more engulfing than the mist outside was leavened somewhat by the fact that, after hours toiling uphill, the stone floor beneath my feet was level. But I was still lost, in silence and invisibility. And then, ahead of me, I saw emerging from the mist, a human, or semihuman, or inhuman figure. Though it was blurry and weirdly shimmering, I sensed that it was ancient, aeons-old, older perhaps than time itself. I did not yet realise that I had come face to face with a Blavatskyite Being Of Unutterable Esoteric Wisdom.

The mysterious figure beckons Dobson to follow him – her? it? – and leads the pamphleteer to a room within a room within a room within a room within a room within a room, an inner inner inner et cetera sanctum, still enshrouded in thick Alpine mist. In the centre of the room stands a stone slab, an altar, upon which are carved inscriptions in several different unknown alphabets. Otherwise, the room is bare, save for an escritoire, an armoire, an arras, a sideboard on which stands a cassette player and a pile of cassette tapes, a much-becushioned sofa bed, a pair of matching musnuds, a two-bar electric fire, a treadmill, a Toc H lamp, a Bakelite figurine of Charles W. Leadbeater, a second stone slab altar without inscriptions, an empotted pugton tree, several vases and basins, a jelly-making kit, a mysterious blue carton, a chemical toilet, a grandfather clock, a drumkit, an easel, a taxidermised weasel, a waste paper bin, an espresso machine, a doormat, a rug, a cat-litter tray, and a few other bittybobs. In one corner there is a mop and a pail.

This was to be my home for the next seventeen years. In all that time, the Alpine mist never dispersed. It remained thick, and occasionally quite swirlyish. So, when I sat in one of the musnuds, I could not see the other one, nor any of the other appurtenances. Moving about my sanctum, I kept bumping into things. My shins were a mass of bruises.

I learned to operate the cassette player, and grew fond of the music recorded on the tapes. Each of them contained ninety minutes of skiffle, performed by Emile ‘Stalebread’ Lacoume & His Razzy Dazzy Spasm Band. I also learned to make jelly.

Once a week, I received a visit from the Blavatskyite Being. It explained that it was going to initiate me into the secrets of the cosmos. To do so, it would read a few paragraphs from The Collected Witterings of Madame Blavatsky, and then quiz me on what I had heard. The questions were put in multiple-choice format, which I found helpful. It had a curious speaking voice, sometimes sounding exactly like the star of stage and screen Jack Hulbert, and at other times like his wife and musical comedy partner Cicely Courtneidge. It might yoyo between the two voices within a single sentence.

Every year, on St Bibblybibdib’s Day, it took me to its own domain, even higher in the Alps. Up there, the air was so thin it could not form a mist, and we had to wear oxygen masks to breathe. All day long we played ping pong on its full-size ping pong table. Oddly, every single game we played over those seventeen years ended in a draw, which is technically impossible when playing ping pong in the mortal world. I hoped one day to find an explanation for this in one of the Madame Blavatsky readings, but it remained a mystery. As did the blue carton in my sanctum, which I was forbidden to open.

Dobson notes that he marked the passage of time, at first by cutting notches in his Alpenstock and later by ticking off the days in an Esoteric Reader’s Digest 17-Year Pocket Diary which he found in the sideboard. Then, one Thursday, the Blavatskyite Being makes an unscheduled appearance. The mist is thicker and swirlier than usual. The pamphleteer is told that he has learned all there is to know, plus a bit more, and is now an Adept Of The Secret Order Of Alpine Blavatskyite Beings (Cadet Class). It is time for him to leave, and to return to the mundane world of mortal men. He is bundled out of his inner inner inner etcetera sanctum none too gently, and given a shove, and skitters down the mountain, through the mist, down and down, until of a sudden the mist clears, and he can see clearly, and to his astonishment, there, sitting on an Alpine municipal bench at the foot of the mountain, waiting for him, is his inamorata and poppet, Marigold Chew.

“Marigold my dearest darling dear!” I cried, “I have returned! I am agog to know what has been going on in the world these past seventeen years. Did the Vietnam War escalate after the Battle of Điện Biên Phủ? Did the Busby Babes win the European Cup? Was it ever proven that Alger Hiss was indeed a Communist spy? Did Emile ‘Stalebread’ Lacoume & His Razzy Dazzy Spasm Band top the hit parade? Uncle Joe Stalin – does he yet live? Are Jack Hulbert and Cicely Courtneidge still high-earning stars in the musical comedy firmament? Has Vice President Nixon published his book Six Crises? I have a million questions to which answers are not vouchsafed even by the secret knowledge I have acquired high, high in the Alpine mist!”

Marigold Chew looks at Dobson as if he has gone mad.

“What on earth are you blathering on about, Dobson?” she says, “You vanished into the mist saying you were going to research all things goaty, and here you are back again, ten minutes later. You can’t have learned much about Alpine goats in that time. And what is that lump on your head? It looks very much as if you have been struck on the bonce by a very large pebble hurled by a mischievous and miscreant young Alpine goatherd boy from the nearby orphanage. We must make a complaint to the beadle to ensure the ne’er-do-well mite is given no jelly for his pudding tonight.”

And with that, Marigold Chew takes Dobson by the arm, and they walk away from the Alps, never to return in this lifetime.

NOTA BENE : Thanks to my old mucker Max Décharné for alerting me to the existence of Emile ‘Stalebread’ Lacoume & His Razzy Dazzy Spasm Band, here.

ANOTHER NOTA BENE : Max has kindly provided a snap of the Razzy Dazzy Spasm Band, taken in 1896 or 1897. As he says, they were proper New Orleans street urchins.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a devotee of Hooting Yard is equally a fan of ’60s beat combo Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Tich, known to Bernard Levin as The Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Tich. That being so, readers will be palpitating with overexcitement at the news that – at long last! – a tribute band has been formed to recreate, as closely as possible, the authentic sound of Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Tich-style poptasticness.

But this is no mere tribute band. It is a supergroup, and a multi-disciplinary one at that, drawing in not just musicians but sports stars, politicians, and statesmen from around the world. Thus we have the Ivory Coast footballer Yaya Touré; the avant garde octogenarian and widow of (in the immortal words of Kenneth Williams) “that Beatle who married an Asiatic woman”, Yoko Ono; the Paris-born American cellist Yo-Yo Ma; and the Israeli politicians Tzipi Livni and Binyamin Netanyahu, known affectionately as “Bibi”.

The group – Yaya, Yoko, Yo-Yo, Tzipi & Bibi – are not yet on tour, nor in the recording studio. In fact they have not yet met up with each other to rehearse such timeless classic hits as “Margareta Lidman”, “He’s A Raver,” and “The Wreck Of The ‘Antoinette’”. It is my fond hope that, reading this press release, each of the five will realise the urgency of making this happen. The future of pop music is in their hands.

ADDENDUM : Dave Dee and his pals graced these pages back in October 2010, when they encountered a bricklaying witch.

In her distant youth, the balletomane Nan Kew was a flapper. Not yet smitten by the ballet, she liked to flap about in speakeasies, getting dizzy on illicit cocktails and executing the latest dance crazes to the sound of boogie woogie and similar musical woogies, as performed by hot jazz quintets led by rascals.

It was in one speakeasy, on 43,722nd Street, that Nan Kew encountered the lumbering walrus-moustached psychopathic serial killer Babinsky. In those days, of course, the phrase “serial killer” had not yet been coined, so Babinsky’s modus operandi remained sub rosa, and he did not have coppers on his trail.

The Helsingfors poliisi may not have had their eyes on Babinsky that night but somebody else did. Lurking in the speakeasy subfusc was the serial killer’s long-lost idiot half-brother, Babinsky 2. He was watching Babinsky’s every move – and what moves! Babinsky was out on the dancefloor, essaying some new dance steps of his own invention, which he called “the lumbering psychopath”. Those of you familiar with the dances of the era will recall it from its abbreviated name, the lumberpsych, which became wildly popular and spawned such hot jazz standards as Papa Done Gone Lopped Off My Limbs Again and Polka Dots, Hair Oil, And Brutality.

Now it so happened that at this time, Babinsky 2 was Nan Kew’s paramour. They seemed an ill-matched couple, the flapper and the idiot, but there was a definite, if inexplicable, chemistry between them. Thus it was that Nan Kew, dizzy on illicit cocktails and slumped somewhat lopsidedly against Babinsky 2 in their booth in the speakeasy gloom, knew without asking why her darling was transfixed by the lumbering brute on the dancefloor. Babinsky 2 longed for a reconciliation with his long-lost brother, from whom he had been parted ever since that catastrophic picnic on the edge of the forest at the end of the war. Or had it been at the beginning of the war? So fuddled was his brain that Babinsky 2 could no longer remember. All he knew was that he had a burning desire to climb trees and play pin-the-antennae-on-the-locust again with his brother, to relive their carefree childhood in the shadow of the Big Formidable Mountains.

But idiot that he was, even Babinsky 2 knew that his half-brother, being a psychopath, wanted nothing more than to drive an axe into his, Babinsky 2’s, skull, and then chop off his head and boil it in one of his horrible grease-encrusted vats in his horrible grease-encrusted cellar beneath his horrible grease-encrusted chalet. And so all he could do was sit in the darkened booth, gazing at Babinsky with love and longing and terror.

Then dizzy Nan Kew had an idea.

“I am sure he won’t recognise you if you don a disguise,” she slurred in her woozy way, “We could get you up as a Levantine toothbrush salesman, or a crippled Dutch ski-lift operative, and Babinsky will never guess your true identity. Then, if we persuade him there is a cuddly little hamster or guinea pig trapped at the top of that sycamore tree in the street outside the speakeasy, the two of you can climb it together, just as if you were carefree tots before that picnic. Meanwhile, I will gather pencil and paper and a pin and a blindfold, and when you come back in you can play that foolish game you were both so fond of.”

“What a fantastic idea!” shouted Babinsky 2, planting a kiss on Nan Kew’s flushed cheek.

“You will just have to convince your half-brother that the hamster or guinea pig atop the tree is an invisible one,” added the flapper, “But that should not prove difficult. Just tell him there has been a plague of invisible small cuddly mammals in Helsingfors and you will show him the press clippings tomorrow. That will give me more than enough time to make some counterfeits on a Gestetner machine.”

Dizzy as she was, Nan Kew was already displaying the resourcefulness which later stood her in such good stead as a balletomane. (See her Memoirs for detailed clarification.)

That night, everything went according to plan. The flapper and the idiot managed to pull the wool over Babinsky’s eyes. The next day, however, it all went wrong. The Gestetner machine was jammed. Mice nibbled at Babinsky 2’s disguise. There was a teeming downpour and thick fog. War broke out following skirmishes on the border at daybreak.

When they went to meet Babinsky at midday on Sawdust Bridge as arranged, the serial killer was armed with his axe and his hatchet and his slicer and god knows what other fearsome sharp implements. Above his walrus moustache, his eyes burned with psychopathic psychopathology. Babinsky 2 and Nan Kew turned tail and fled through the narrow Helsingfors streets.

It would be forty years before the half-brothers met again. During all that time, Babinsky 2 treasured his memories of that one evening. For a cherished hour, Babinsky and Babinsky 2 had relived the idyll of their pre-picnic childhood, all thanks to the quick wits of future balletomane Nan Kew!

This article first appeared in The Weekly Intelligencer Regarding The Doings Of Flappers, Idiots, & Serial Killers In & Around The Speakeasies Of Antebellum Helsingfors (obtainable by subscription).

Trudging through the countryside the other day, I saw ahead of me a couple of peasants, standing at the edge of a bog, deep in conversation. It is well-known that the talk of peasants consists almost exclusively of rustic lore and wisdom expressed in the form of age-old sayings and proverbs. Thus it was no surprise to me when the snatch of their talk I overheard as I passed them by was one such old saying. What was unexpected was that it was one I had never heard before.

“A ghoul and his monkey are soon martyred,” one peasant muttered, in the lugubrious tones of peasants the world over. His companion said something in reply, but the words were swept away on the wind, and I heard them not. I was trudging at a pretty fair crack, so I was almost immediately out of earshot. I considered, for a moment, turning about and interrogating the peasant regarding his utterance, but I quickly dismissed the thought. Trying to wring sense out of a peasant is almost always, as one might put it, a fool’s errand.

I was still thinking about what I had overheard when I arrived home. Usually, proverbs and sayings express a self-evident truth, what we might call common sense. A stitch in time saves nine and a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush are examples of such folk wisdom, passed down through the generations. But – I wondered – is it equally true that a ghoul and his monkey are soon martyred?

After making a cup of ersatz cocoa-style boiling beige water, I heaved down from the bookshelf the two fat volumes of the fourth edition of Actes and Monuments of these Latter and Perillous Days, Touching Matters of the Church (1583) by John Foxe, commonly known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. This is my indispensable guide whenever I contemplate martyrdom. Admittedly, I do not do so very often, and I had to remove an encrustation of dust and grime from both volumes, using my trusty rag. That done, I felt confident that somewhere within the more than two thousand folio pages of Foxe’s mighty work I would find confirmation of martyred ghouls and monkeys.

Several hours later, my brow was furrowed, my eyes were bleary, and my once boiling beige cocoa-style water was stone cold. I slammed shut volume one of the Book of Martyrs having failed to discover a single reference to either a ghoul or a monkey. This was most disconcerting. Before pressing on with the second hefty volume, I tried to clear my head by practising Tranche Seven of Baxter’s Head-Clearing Exercises. Tranches Two and Five are usually most efficacious, in my experience, but a quick rummage in the pantry revealed that I was fresh out of paper pastry cases. Also, I remembered that I had loaned my milk stamps to Bruno, so Tranche Seven it would have to be.

Head semi-cleared, I reheated my drink over a gas-jet and slumped back in my armchair with Volume Two. Damn and blast John Foxe!, I shouted to the ceiling at dusk, as the shades of night gathered in the dimpled and disgusting sky, for I had fought my way through another thousand pages with neither hide nor hair of a ghoul or a monkey coming to light. It was at this point that I first began to doubt the veracity of that peasant I had overheard, so many hours ago. Surely, if a ghoul and his monkey were soon martyred, or indeed martyred at all, sooner or later, then they could not have escaped John Foxe’s notice? And yet they had.

I slept uneasily, but awoke in the morning with a renewed sense of purpose. A question thumped and rethumped in my head. Could I infer from the proverb that every ghoul had his own monkey? That no ghoul was, as it were, monkeyless? Or did the saying simply point out that those ghouls who did have monkeys were soon martyred, along with their monkeys? Were there ghouls without monkeys who were immune from martyrdom? I could have lain in bed all day, letting these conundra, if that is a word, swirl around in my head. But if I did so I would be as mad as a pedal bin full of guinea pigs by lunchtime, so I leapt out of bed, cut three or four Boswellian capers around the room, and, after abluting and tucking into what our Flemish pals call het ontbijt, I went to the nearest zoo.

My theory was that I would find evidence of ghouls in or around the Monkey House. If I was lucky, I might even find a ghoul and a monkey together, perhaps being subjected to a hideous and barbaric execution, burned at a stake for example. This was not likely, however. I suspected that any diligent zookeeper – and are there any other kind? – would put a stop to such shenanigans. No, the martyrdom of a ghoul and his monkey would never take place in a well-regulated zoo. They would be dragged away by their persecutors, to a gibbet atop a tor silhouetted against an awful sky, say, or to a dungeon beneath a temple fort. What, then, could I hope to discover at the zoo?

To answer this niggling question, I turned, as I so often do, to Arthur Ira Garfunkel. Half a century ago, the G, as he is known to his close friends, had sung about being at a zoo. If I could only remember the words, I felt sure they would guide me. I tried to summon the song in my head, but though I recalled mentions of monkeys, giraffes, and hamsters – hamsters? – there was not a single ghoul. This flummoxed me, until a passing zookeeper, hearing my humming, pointed out that somebody else had written the words. The G was just singing them – they were not pure authentic Garfunkelisms. I was crushed, and all the more so when the same zookeeper told me that, it being Thursday, the Monkey House was padlocked shut. It was the monkeys’ day off, he explained. He plodded away, thin, undead, and spectral, clanking his chains and groaning. I went home.

After taking an uneasy nap, I sat up and reviewed the situation, Thus far, my research had focused on martyrs and monkeys. Yet the proverb clearly placed ghouls at the forefront. I was working backwards! I plunged my head into a basin of ice-cold water (Tranche Four), tossed some ectoplasm into my pippy bag, hoicked it over my shoulder, and pranced out of the door, affecting a determined jut of the jaw as if I were the actor Bernard Lee in The Third Man (Carol Reed, 1949). Pausing at the corner to belatedly tie my shoelaces, I headed straight for my local branch of Ghouls R Us.

Once inside, I went up to the counter and rang the bell. Its peal was funereal and redolent of death, bats, and sepulchres. I waited for several minutes until, from behind a veil of cobwebs, a sales assistant appeared. I was immediately struck by how close a resemblance he bore to the zookeeper I had met that morning. He was thin and undead and spectral, clanking his chains and groaning. I was about to ask him if he had a brother working at the zoo, but I stopped myself. I had devised a clever plan, and I must stick to it. Watching him closely, alert to the faintest of reactions, I said:

“Good afternoon. Do you have any monkeys for rental?”

The flesh of his eyelids had rotted away, but was that the ghost trace of a blink? His lips, too, had long ago been eaten by worms, but did I discern the shadow of trembling? So foul was his countenance I could not be sure. Then he spoke, and his voice came as if from a deep and desolate tomb a thousand miles distant.

“No,” he said, and it was all he said, and then, before my eyes, he crumbled to dust, leaving only a cloud of vapour hovering in the mephitic air. I turned on my heel and ran all the way home, gibbering.

I woke bright and early the next morning. While shovelling het ontbijt down my gob, I heard the whistling of the postie. He was an embittered postie – how to explain his cheerful whistle? Perhaps I ought to devote the day to solving that little puzzle. It would take my mind off ghouls and monkeys and martyrdom.

Among the bills and flyers and religious tracts in the day’s delivery, I was delighted to find the latest edition of the Reader’s Digest. Having made my usual check to ensure the apostrophe in the title was correctly placed, obviating the need to write a letter of complaint to the editor, I browsed the contents page. I looked forward to reading “I Am John’s Head” and “Fighting The Communist Menace”, among other articles. And if I had the time, I would skim through a piece entitled “When Peasants Mutter, How Easy It Is To Mishear Their Wise Old Sayings!”

Placing the magazine on my windowsill magazine placement contraption, I looked out and saw, on the village green, they were erecting the gibbet for that afternoon’s simian zombie heretic hangings.

On 28 December 1973, I attended my first gig. I had been taken to concerts before, notably (and inexplicably) by my father to the Albert Hall to see the absurd gravel-throated troubadour Rod McKuen, but this winter’s night was my first outing, unaccompanied by an adult, to the world of rock. My friend Paul Pearce and I took the Central Line into London from our homes in the blighted wastelands of suburban Essex, and fetched up at the Lyceum, just off the Strand. We had come to see … Gong (or The Gong, as Bernard Levin would have it).

Now, bear in mind that I was a wet-behind-the-ears young teenperson. Molesworth would have called me uterly wet and a weed, and he would have been right. Somehow, in the preceding months, I had managed to convince myself that a bunch of drug-addled hippies caterwauling about gnomes and flying teapots represented a world I was avid to be part of.

Many of my schoolfriends were in thrall to glam rock, but I pooh-poohed Marc Bolan and David Bowie and their ilk as hideously commercial. I veered towards what I thought of as the progressive and the underground, and Gong fitted the bill. So there were Paul Pearce and I, wide-eyed and innocent, surrounded by long hair and beards and kaftans and foul-smelling Afghan coats, while on stage Daevid Allen and his chums caterwauled and parped and made the kind of din I told myself I adored.

Being wet and weedy, Paul and I of course had to ensure we did not miss the last tube train home, so we left the gig early. My memory is dim, but I suspect I was elated. I had seen my future, or so I thought. I would live in a filthy commune and take lots of drugs and reject straight society and possibly even strum a guitar.

It did not quite work out like that, though the dream lingered for a couple more years. I went to lots more gigs, and saw Soft Machine and Stackridge and Henry Cow and Wally and Kevin Coyne and Jethro Tull and Hatfield & The North and many others. But I never saw Gong again.